Rethinking amateur photography

Historian Dr Annebella Pollen talks about her investigation of the amateur photographer

27 Jan 2014

Why is the most popular form of photography so often taken the least seriously? Why is the largest form of photographic practice considered less interesting than the work of the select few photographers who are included in the canon of ‘greats’? Why are amateur photographs so often derided as thoughtless, banal and clichéd?

For several years now a central theme of my research has been an attempt to answer these questions through a series of investigations into mass photographic practice and its histories. These enquiries have taken me from private family albums to major company archives, from the special conservation conditions of historical repositories to abandoned photographs in car boot sales, from single precious images to vast online image platforms. In each case my concern has been to investigate overlooked material, to reconsider its value and to find new ways of interpreting the ubiquitous yet somehow elusive form of popular photography. Ordinary and everywhere, such images are part of the fabric of our daily lives yet they can be hard to grasp, precisely because of their familiarity and, increasingly, their quantity.

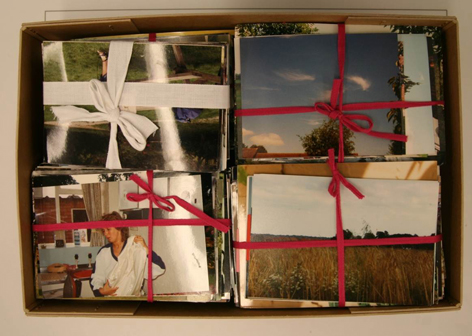

In my AHRC-funded PhD research (2007-10), I worked with an archive of 55,000 photographs of British everyday life, taken on a single day in 1987, as a means of examining pre-digital amateur photographic practice on a massive scale. This involved scrutinising every single photograph in the archive, alongside historical research into the origins of the One Day for Life organisation that solicited them. Through interviews with hundreds of founders, participants, judges, editors, publishers and archivists, I examined the ways in which the photographs could be variously used to raise money for charity, to provide a form of popular documentary, to perform identity, to compete aesthetically, to prompt laughter and tears, to sell books, to anticipate memory and to make history. I have discussed the sometimes conflicting narratives and counter-narratives that such photographs could tell in a range of local, national and international conferences, and in my publications, for example, in the chapter, ‘The Book the Nation is Waiting For! One Day for Life’, in The Photobook from Talbot to Ruscha and Beyond (I. B. Tauris, 2012) and in the journal article, ‘Historians in two hundred years' time are going to die for that! Historiography and Temporality in the One Day for Life Photography Archive', History and Memory (25:2, Fall / Winter 2013).

"user-generated projects often seek to secure a snapshot of a single day as means to create a global community, as a source for collective understanding"

The methods I devised for interpreting large archives of photographs have been featured as a highlighted case study in Penny Tinkler’s book Using Photographs in Historical and Social Research (Sage, 2013), and this research project will also feed into my first book, Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life (I. B. Tauris, 2015), which will examine the enduring popularity of day-in-the-life participatory media projects. With increasingly accessible camera technology and the apparently democratic nature of digital communication, these ‘crowdsourced’, user-generated projects often seek to secure a snapshot of a single day as means to create a global community, as a source for collective understanding, and as a visual time capsule for an unspecified future. Mass Photography will be the first book to examine these ambitious photographic phenomena; as such it aims to cover new ground and tocontribute to photographic history and theory by taking a fresh look at amateur practice on a large scale.

Another aspect of my project to take amateur photography seriously considers those who might describe themselves as ‘serious amateurs’ - a much-ignored and even dismissed group in photographic studies. My research into camera clubs and photographic competitions illuminates enduring debates about what might make a ‘good’ photograph, where these rules come from, and who gets to judge. Together with colleagues in the Ph: Photography Research Network (which I co-convene), I have been commissioning and editing National Media Museum-funded web content for the Either/And project, which considers the place of the photograph in contemporary culture.

"I uncovered how photographic practice is a product of public as well as private desires"

With contributions from a broad range of international scholars and practitioners, curators and picture editors, my co-edited strand, Reconsidering Amateur Photography, resulted in twenty essays and an accompanying event, held at University of Brighton in 2012. My own contribution to this series, the essay ‘When is a Cliché not a Cliché?’, examined the supreme popularity of the sunset in amateur photographic practice, and was recently picked up in an article by The Guardian, entitled ‘Sunsets: The Marmite of the Photography World’. The full collection of Either / And material will be appearing in a National Media Museum publication in 2014.

Other related research in this vein has focused on the role of the market in shaping popular photographic practice. Amateur photography, with its emphasis on communication, memory and familial or domestic subject matter, is sometimes seen as the most authentic form of photography, somehow less self-conscious than photography that aspires to be art.

Some have even described popular photography as a kind of simple folk art, and these claims continue in the fashionable market for so-called ‘vernacular’ photographs. Others claim that the photographic industry has had an overbearing effect on shaping the subjects and styles of popular photography, through their advertising, control of technology and primary need for profit. To examine how these debates play out in practice, I examined the previously-unseen historical archives of Boots the Chemist, who dominated the British photo processing industry throughout the twentieth century; indeed, who were once synonymous with popular photographic printing. Through examining the rise and fall of the photographic department alongside their photographic guidance and prohibitions, I uncovered how photographic practice is a product of public as well as private desires. Aspects of this research have been shared at two 2013 photographic conferences: Workers and Consumers: The Photographic Industry at De Montfort University and Professional Photography and Amateur Snapshots: Reconstructing Histories of Influence, Dialogue and Subversion at University of Nottingham. This research is also due to appear in print as a chapter in the forthcoming Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Photography.

At the close of 2013, the Oxford English Dictionary announced that their new word of the year was ‘Selfie’, meaning a self-portrait taken with a hand-held digital camera or camera phone. To begin 2014, appropriately, I will be leading a panel on this subject for the National Portrait Gallery, joined by photographers and photography theorists, a philosopher and a neuroscientist. Entitled ‘Curating the Ego: What Makes a Good Selfie?’ the panel event will discuss ideas about identity, memory, performance and taste that affect all who take photographs and, indeed, who appear in them and view them. To take popular photography seriously is, after all, to take the popular culture of everyday life seriously, for in the 21st century, we are all photographers, photographic subjects and photographic critics, looking and being looked at, all of the time.

Dr Annebella Pollen is a researcher in the history of design and material culture at the University of Brighton Faculty of Arts. She is editor of Reconsidering Amateur Photography, and led a panel at the National Portrait Gallery's event ‘Curating the Ego: What Makes a Good Selfie?’