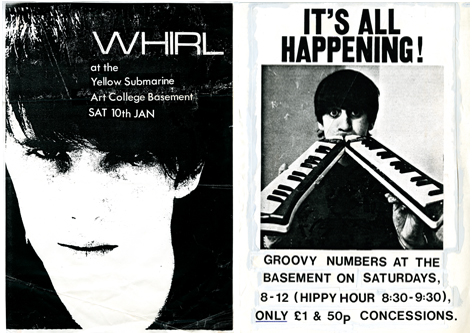

LEFT: 'Whirl' poster. With kind permission of Josh Dean. RIGHT: 'It's all happening!' poster. With kind permission of Josh Dean.

LEFT: 'Whirl' poster. With kind permission of Josh Dean. RIGHT: 'It's all happening!' poster. With kind permission of Josh Dean.Chapter text, Jonathan M Woodham[1]

The dark, dingy, wet-floored, low-ceilinged series of interconnecting spaces known as The Basement were located on the lower ground floor of the rambling Glenside Annexe immediately adjacent to the main College of Art building[2] in Grand Parade[3]. Despite the somewhat gloomy, unappealing first impression this ‘rabbit warren’ gave off, it held a special place in Brighton (sub) culture, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s when it became a highly popular venue with its ethos of fashion, anti-fashion and all the stylistic idiosyncrasies and vivacity associated with art school life. Described by some as ‘a rite of passage’, it was managed through the Students’ Union – and was, at times, a considerable source of Union income. The Basement hosted many bands in early career, such as U2, Echo & the Bunnymen, New Order and The Levellers: it was a bar, a dance club and performance arena and was, in the 1970s, at the vanguard of the clubbing scene before the establishment of the Zap Club, a staging post for late night and early morning music and dance venues such as the Vault, the Alhambra, the Buccaneer and the Savannah Club. It had also provided a rallying point in the 1968 art student revolution in Brighton (see Chapter 5) and, in the occupation of 1991, ‘the nerve centre of heated debates and the legendary ‘Occubops’ where performance and polemic and student activism was alive and well, albeit for a relatively short time.’[4] It even had its own resident ghost, witnessed by a number of people working there, rumoured to have been a former janitor killed by a bomb in the Second World War.[5]

Perhaps most widely known for the Friday Night Club that had been established by the 1960s, The Basement was not then an absolutely intrinsic facet of student life. But, by the 1970s, it had become a key venue for Brighton students, having the twin advantages of a town centre location and a distinctive club ethos, unlike the rather more conventional and larger out of town student performance venues at Sussex University and Brighton Polytechnic. Following the 1976 election of Neil Butler (later a co-founder and co-director of the Zap Club) as Vice-President of Brighton Polytechnic Students’ Union with responsibility for communications and entertainment, Grand Parade became more of a focal point for performance. He put on regular events in both the Sallis Benney Theatre and The Basement, working closely with poet-performer Roger Ely. The latter had enrolled at the Polytechnic’s Art Teachers’ Centre in Sussex Square in 1976, then still a part of the Faculty of Art & Design. He had initiated a series of art, poetry and music events at Sussex Square, but the Head of the Centre objected to the content of the programme, particularly a performance monologue by Dave Stephens entitled Filth in November 1976. Butler and Ely[6] also founded and organised the Brighton Contemporary Festival of the Arts (1977-79), an important impetus in the genesis of Brighton alternative culture. The first Festival embraced many venues across Brighton, including the Sallis Benney Theatre, the adjacent Norfolk Public House (now Hector’s House) and The Basement itself. Performances at the latter included the Liverpool poet Adrian Henri, guitarist Andy Roberts, saxophonists Evan Parker and Lol Coxhill, the Mike Osborne Quintet, the George Khan Quartet Mirage, and performance artists Stuart Brisley, Diz Willis, and Kevin Atherton. A similarly adventurous line-up infused subsequent Festivals and did much to enhance the cultural horizons of the town. Also connected with The Basement, albeit as a doorman, was Dave Reeves[7], a close friend of Butler’s and future co-founder and co-director of the Zap Club[8] that, in the 1980s, went on to take the alternative cultural agenda of The Basement several stages further. Bands put on above ground in the Sallis Benney Theatre at the time included Siouxsie & the Banshees and The Stranglers, both playing to packed audiences. There were also rather more mainstream performances such as readings by celebrated German-born poet Michael Hamburger, and a programme by the London Contemporary Dance Theatre and the Mike Westwood Band.

An important ingredient in the later 1970s art student ethos was the Faculty of Art & Design’s innovative Expressive Arts degree course[9] launched in 1978, bringing together the visual arts, theatre, music, dance and performance, with young dance and music lecturers, choreographer Liz Agiss and musician Billy Cowie, and gifted students such as Ian Smith[10], providing a bridge between the art faculty and performances at new, alternative venues in Brighton, such as the Zap Club. Cowie’s post-punk band, Birds with Ears, included Smith, was formed in 1980 and performed in The Basement early in its life: ‘Popular live, the band played to packed houses in Brighton and London with an outrageous show featuring Ian Smith decked out in a bird-shit spattered tux, strobe lights and amazing sound effects.’[11]

Punk and New Wave were powerful stimuli in the late 1970s and early 80s and were much in evidence in musical promotions at The Basement, particularly those put on by entrepreneurial graphic design student Addison Cresswell[12] who oversaw the marked transition away from the Basement’s Friday Night Club predilection for Heavy Metal music towards more cutting edge Punk and New Wave developments. In his First Year he met Anthony Wilson with whom he worked closely on the Friday Night Club. The latter was at this time generating far less money than hoped for by the Students’ Union, which was responsible for The Basement’s management. One of Cresswell’s innovations was to establish a Tuesday Night Club as a counterpart to its Friday antecedent. As Alan Williams, an ambitious 20 year-old who was employed to set up PA systems during much of the life of The Basement from c.1980 onwards, remarked: ‘Addison was a key figure in the presentation of bands, with his gigs usually selling out. He was one of the few people able to break the Friday Night Club regime.’[13]

Image: 'Jasmine Minks' poster. With kind permission of Josh Dean.

Image: 'Jasmine Minks' poster. With kind permission of Josh Dean.Sell-out gigs necessitated adequate security arrangements. Cresswell had taken over the running of music events at a time when there had been a number of petty thefts on the Grand Parade site, with blame often laid in the direction of Punk Rockers from outside the Polytechnic. Cresswell solved two problems at a stroke by striking a deal with members of the Brighton punk rock community, employing seven of them, including ‘Big Mark’ and ‘Scottish Doug’. Referred to by Cresswell as the Magnificent Seven, they provided security for The Basement Club at £1 a night each. He also oversaw the construction of a proper bar and made the venue like a fortress, entered through a narrow space via steps in Grand Parade.

In order to change the feel of the Friday Night Club a fresh approach was required for presenting bands. Rather than dealing with promoters who often let them down, Cresswell and Anthony Wilson looked to a number of record labels that had emerged in the punk and new wave milieu of the late 1970s, three of them being established in 1978, the year Addison took over music events at The Basement.[14] As a result they dealt with subsequently high-profile figures such as Tony Wilson, co-founder (with Peter Saville and three others) of Factory Records and owner of the legendary Hacienda nightclub in Manchester. They also liaised with Geoff Travis’s London-based post-punk record label Rough Trade, as well as the independent, Liverpool-based Zoo Records label, founded by Bill Drummond and David Balfe. Drummond was the manager of Echo & The Bunnymen, one of many bands put on by Cresswell and Wilson in The Basement.

Cresswell also recognised the importance of publicity in helping to ensure sell-out events and sought to get his gigs featured in the national music press. He looked to NME (New Musical Express), which had undergone a change of editorship in 1978 as well as a complete redesign by Barney Bubbles, to Sounds, one of the first music papers to pick up on Punk, and to Melody Maker. In Brighton, The Argus also carried a number of features. As a graphic design student Cresswell designed a number of posters for Basement promotions that, like so many records of ephemeral events, are no longer extant.

But despite all the professional instincts of Cresswell and Wilson in terms of music promotion itself, The Basement Club was still a dark, labyrinthine, often wet-floored, cramped space with a safety limit of 200.[15] The makeshift stage was constructed from ply-board supported on either beer crates or wooden pallets, but couldn’t be built too high as the ceiling was so low. Bands would usually perform in front of the fire exit with a minimal space to get through and the PA system was set up on a couple of tables which all but blocked off the ladies’ lavatories, leaving a gap of little more than 18-inches for women to push through. Nonetheless, it did not prevent the Basement becoming a highly popular venue for art students or outsiders.

Few bands provided any requirements in advance and so there were many improvised solutions for equipment set-up. Sometimes there were more microphones than microphone stands, resulting in some being hung from the ceiling. Such ad-hocism extended to one of Cresswell’s earlier promotions, the Irish band U2 who were booked through the London-based agency Wasted Talent for what has been said to have been their second UK performance.[16] When asked by Bono on arrival about lighting set-ups for the band, Cresswell pointed to two spotlights - one red and one white, purchased from B&Q – and told him that the white was for him and the red for the band. Other memorable occasions included the appearance of post-punk band Killing Joke, complete with hazardous fire-eater, who singed the low ceiling. The ceiling height also caused other serious problems: when the Norwich punk rock band Serious Drinking played, its lead singer hit his head against a low beam and knocked himself out. Colin Matthews[17] also relates how, on one occasion when the walls were lined with aluminium foil to provide a particularly striking effect, there were serious concerns that the humid atmosphere might short out the electrics or give off electric shocks.

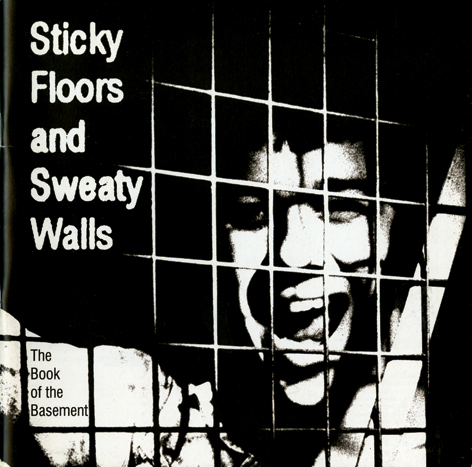

Image: Cover, Sticky floors and sweaty walls. The Basement Club book.

Image: Cover, Sticky floors and sweaty walls. The Basement Club book.The Liverpudlian band Echo & the Bunnymen played in The Basement at about the time of their debut album, Crocodiles (1980), which reached number 17 in the UK Albums Chart. They were paid £150 cash, rather than the more customary £100 and the event was recalled by an e-mail contributor to The Bunnymen Concert Log 1978-79:

I think it was probably towards the end of 1979 but maybe early 1980; it was definitely winter as I remember it being freezing waiting at the door. As we were walking down from the station, and were just up the road from the Basement a white van pulled up and a scouser leaned out the window and asked me and my mate ‘where's the Basement Club?’ - we didn't realise until after it was too late to swap directions for two places on the guest list, that the lads in the van were the Bunnymen …[18]

Another band booked by Cresswell was Manchester-based Joy Division, whose first album was released on the Factory label. Unfortunately, their vocalist, Ian Curtis, committed suicide in May 1980, but the remaining members formed New Order: The Basement was the venue for their first gig. DJ John Peel’s Radio 1 Sessions featured several bands staged by Cresswell at this time. These included the post-punk Swell Maps; the Mo-dettes, an all-female punk band formed by Kate Korus; and the beat-punk Nicky and the Dots, who recorded on the Small Wonder label.[19] The Students Union must have been highly indebted to Cresswell as he regularly paid over to them large sums of money generated by his promotions. However, his entrepreneurial drive also extended to hiring – with Tony Wilson and Colin Matthews – The Basement from the Students Union during the summer vacations when it would ordinarily have been closed. Their audiences were largely drawn from overseas students at the many language schools in Brighton, according to Cresswell, a constituency dominated by “Scandinavians and silver jump suits”.[20] It was also at this period that a sign to ‘Addisono’s’ was erected for a very brief period outside the entrance to The Basement, in contravention of local planning legislation.

Cresswell and the Students Union also made use of the much larger, but less colourful, Sallis Benney Theatre for major gigs, with occasional problematic results. One regular audience member remembered:

Throbbing Gristle[21] being bottled off in a hail of noise and abuse, The Fall[22] ending in a big fight and Madness being invaded by skinheads … but this was upstairs in the Sallis Benney [Theatre] with the Basement as the Bar, so gigs were stopped upstairs and bands transferred to the Basement.[23]

Pop-ska band Madness were paid £250 cash, with the Brighton-based mod revival Lambrettas in support; 2 Tone ska revivalists The Beat also received £250. Other bands put on included The Ruts, a reggae-influenced British punk rock band that gained headline attention in 1979 with their Top 10 hit Babylon’s Burning. However, Cresswell’s association with The Basement diminished somewhat in his final year in 1981, as he focused more on his graphic design coursework.

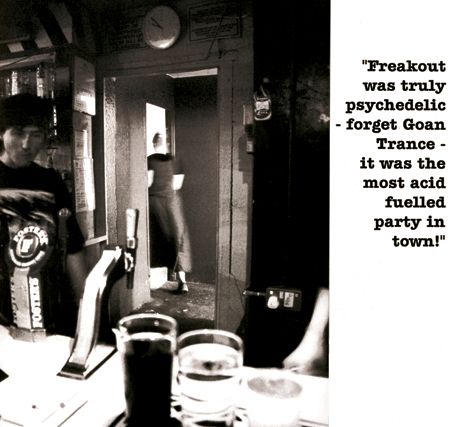

Image: Page spread from Sticky floors and sweaty walls. The Basement Club book.

Image: Page spread from Sticky floors and sweaty walls. The Basement Club book.In this period DJs in The Basement included Derek Furnival[24] who had come to Brighton in 1981 and sometimes ‘filled in’ between bands. A punk-rocker non-student regular in the club, he played music that included Cabaret Voltaire, Throbbing Gristle and a variety of bands from the Attrix Records label and shop in Sydney Street, Brighton, where music by the Dead Kennedys, the New York Dolls, the B52s, The Damned and other Punk and New Wave bands were sold.

Late in 1982 the premises was ‘improved’ and Mal Smith[25] was employed as its manager by the Students’ Union for seven terms, commencing in 1983. The Basement - or ‘Debasement’ as it was sometimes affectionately known - was still viewed as something of a ‘cash cow’ by the Students’ Union and so the Friday Night Club was a central part of Smith’s responsibilities. Bar sales were central to income: for the Friday Night Club entrance was 50p, with spirits at 40p a shot and beer at 60p a pint. On a good evening the takings were about £1000 a night, facilitated by the lager dispensing technique (known as ‘lager duty’), whereby a member of bar staff was assigned to a constant filling of pints with the beer tap never turned off - a somewhat primitive but effective means of satisfying the thirsty hordes. This was an invention born of necessity, as the two bars were tiny, under 6 feet wide with five people serving behind them. People management skills were also critical as the alcohol licence only lasted until 11pm whereas the dance and music licence finished an hour later. With a limit of 200 people in the confines of The Basement, this often proved difficult with many people ordering up several pints before the bar was firmly closed behind its heavy metal lockable shutters. One technique for emptying the premises was to flood it with the harsh white light of glaring spotlights. Nonetheless, there was comparatively little trouble and, although the police were called from time to time, it was usually over by the time they arrived. It was said[26] that the door staff in the early 1980s were experienced in Tae Kwon Do, but those actually taking the entry money were generally students. Although The Basement’s official policy was to restrict entrance to National Union of Students’ card-bearers, discretion largely lay with door staff - as had been the case for much of its existence. At one time there was occasional trouble between the mod-revivalist ‘Scooter Boys’ from outside the Faculty and the graphic design students from within. There was also, as one bar worker confirmed[27], a baseball bat behind the bar that was occasionally called into action.

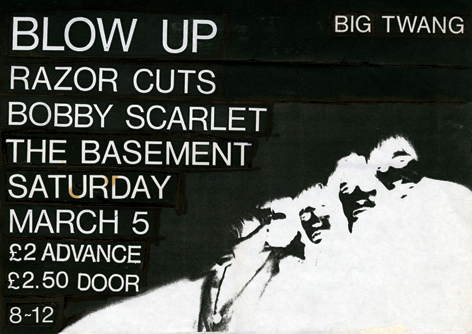

Image: 'Blow up' poster. With kind permission of Josh Dean.

Image: 'Blow up' poster. With kind permission of Josh Dean.Various efforts were made to liven up other evenings to generate additional income, although the general ethos was more of a dance club than a music venue. However, bands still performed through the decade. In 1988, for instance, The Levellers, with Brighton fine art graduate Jeremy Cunningham on bass, had their debut in The Basement. Also during the 1980s presentations relating to other media reflected something of the diversity of interests promoted by Roger Ely in the late 1970s, including one by film director Derek Jarman. A few years earlier, he had made Jubilee, featuring a number of punk bands, and was, in the 1980s, one of the few gay public figures in Britain campaigning against restrictive legislation. Rastafarian writer and dub poet Benjamin Zephaniah also performed in The Basement although, unfortunately, without a working microphone.

There were short-lived ventures such as ‘The Wardrobe Club’, entered through a wardrobe, as with The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, and the rather more ambitious ‘Hot Club’ night where The Basement was made over as a jazz venue to attract a non-student, as well as student, audience. Tables were laid out, café style, with candles, although this lasted for little more than four weeks as it proved difficult to attract enough paying audience members or musicians to play. Cocktail Nights were also promoted, along with more run of the mill spirits promotions: Whisky Nights proved subdued, Tequila Nights were really lively (assisted by countless ‘slammers’), but Pernod Nights generally less popular; ‘Snakebites’, ‘Swampwaters’ and ‘Black Buggers’ were more everyday drink recipes for ‘a good time’. There were also ‘Women Only’ nights on Tuesdays where a women’s disco collective provided the DJs, individuals taking it in weekly turns to play music. In tune with the formation of many women’s groups at the time this weekly event coincided with the early years of the Women’s Peace Camp that had set up at Greenham Common in 1981 and, although modest in terms of numbers, Tuesday evenings provided a supportive social atmosphere where women could meet and dance after a hard day in the studios. Musical tastes of the time ranged from Grace Jones’s Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing to Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s The Message.

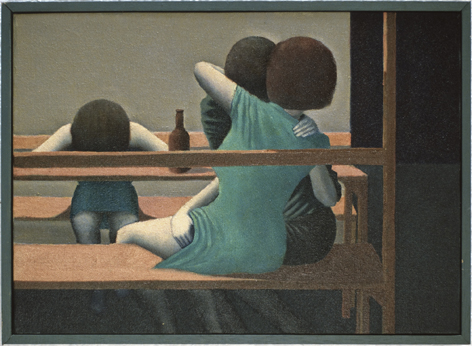

Image: Christopher Stephes, 'Shaun and Cinylou'.

Image: Christopher Stephes, 'Shaun and Cinylou'.Josh Dean[28], who had enrolled for the British Studies degree at the Falmer site of the Polytechnic, was elected as Social Secretary and later Vice-President (Communications) of the Brighton Polytechnic Students Union. He moved to the BPSU’s Glenside offices above The Basement at Grand Parade,[29] and was involved with the Friday Night Club for several years, booking bands for about three years and DJ-ing for several more, as well as being involved with Saturday night ‘Freak Outs’. The latter (full title ‘Saturday Freak Out in Strobes and Smoke to the Music of Hendrix, Hawkwind and Zappa’), were held monthly. The club atmosphere was enhanced by oil wheels producing psychedelic lighting effects of merging and evolving colours and patterns, smoke machines, often pumped by hand around the dance floor, and flashing strobes. Other music featured a wide range of indie performers as well as ska, Motown and Northern Soul, one Northern Soul night attracting the attention of Crawley skinheads who wanted to close it down. Bands that played at the Basement in this period included Scottish alternative rock band Primal Scream who played in 1987 with tickets at £1, the Brighton Anarcho-punk Poison Girls, the Redskins (socialist skinheads), the less politically challenging Little Green Hondas (Visual and Performing Arts graduates with a Beach Boys flavour) and the Marine Girls (with Jane and Alice Fox on bass and vocals[30], both now lecturers in the School of Arts & Communication), who featured in two John Peel Radio Sessions in the early 1980s and whose album Beach Party was widely played. During the decade The Basement continued to provide a platform for other forms of alternative performance including punk Porky the Poet (better known today as the comedian Phil Jupitus) and pioneering woman punk performance poet Joolz.

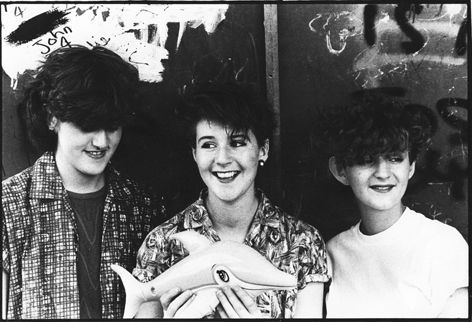

Image: 'Marine Girls' publicity photograph. With kind permission of Jane and Alice Fox. Photograph by Huw Davies, 1981.

Image: 'Marine Girls' publicity photograph. With kind permission of Jane and Alice Fox. Photograph by Huw Davies, 1981.It remained a feature of art student life (in various successive guises, as part of the Brighton College of Art, Polytechnic and University) until its closure in 1996 for the demolition and rebuilding of the Glenside Annexe. Many memories were captured in a slim commemorative booklet published to accompany a farewell exhibition. Entitled Sticky Floors and Sweaty Walls: The Book of the Basement, it was published in 1996 by the University of Brighton Students Union, with reference to many who had passed through its doors other than those mentioned above. They included guitarist and vocalist of Supergrass, Gaz Coombes, dancing, Graham Coxon, guitarist of Blur, playing a set, and Paul Cook with Steve Jones, drummer and guitarist of the Sex Pistols, together with the band’s vocalist John Lydon’s brother Jimmy, drinking at the bar.

Image: The Basement Club. The Design Archives.

Image: The Basement Club. The Design Archives.Some have said that when The Basement’s licence was extended to 2.00 am the atmosphere lost something of its edge, the venue becoming a place to stay for the night rather than the first stage of an extended evening out. Nonetheless, whether or not the truth of this view, the post-club evening for many would end with a ‘Gut Buster’ at the nearby all-night Market Diner. The latter had a particular place in Brighton nightlife and was later described in The Observer as ‘a plastic palace for the wide-eyed and, more often than not, legless. A listed building a stone's throw from the Royal Pavilion, the Market Diner is full of chilled-out clubbers. Drunks and students (and drunken students) sit shoulder to shoulder, mulling over the burning issues of the day, like whether chips have any place in the full English breakfast.’[31]

Image: Grab Grab the Haddock and the Television Personalities photograph, c.1985. With kind permission of Jane and Alice Fox.

Image: Grab Grab the Haddock and the Television Personalities photograph, c.1985. With kind permission of Jane and Alice Fox.[1] Many people have contributed their memories of the Basement for which the author is very grateful, the most significant being acknowledged either in the text or footnotes.

[2]It later became the Faculty of Art and Design building of Brighton Polytechnic; currently, the Faculty of Arts & Architecture of the University of Brighton.

[3] Completely rebuilt by the University in 1998: much of the former basement now houses the Design Archives and the Aldrich Collection store, the floor above the Faculty’s Centre for Research and Development and, above that, Graphic Design offices and studios.

[4] Melita Dennett, Sticky Floors and Sweaty Walls: The Book of the Basement, Brighton: University of Brighton Students Union, 1996, p.16.

[5] Addison Cresswell, in an interview with the author, 10 September 2008, recounted his experience of the ghost that had also been seen on different occasions by the Basement’s manager at the time. In Brighton, there were 198 deaths from bombings recorded in the Second World War.

[6] The author is particularly grateful for Roger Ely’s help with regard to material and dates relating to the Contemporary Festivals of the Arts.

[7] Interviewed by the author on 16 September 2008.

[8] Max Crisfield (ed), ZAP: Twenty-five Years of Innovation, Brighton: Zap Art/QueensPark Books, 2007.

[9] Now a suite of Performance & Visual Arts degree courses, with options in music, dance and theatre.

[10] Ian Smith went on to become a key figure as MC at the Zap Club in the 1980s, worked for Archaos and set up an experimental performance group, Mischief La Bas in the 1990s, and has been a regular MC at the National review of Live Art in the 200s.

[11] http://www.punkbrighton.co.uk/bwe.html

[12] Addison Cresswell s the MD of the London-based Off the Kerb Productions, the agency for major stars such as Jonathan Ross, Jack Dee and Lee Evans. He was interviewed by the author in his London offices on 10 September, 2008.

[13] Interview by the author on 3 September 2008. Williams was not a student at Brighton but became very much involved with music events in Brighton, having raised a large bank loan as a 20 year old to buy an expensive PA rig, giving himself a professional advantage in Brighton clubs and performance venues for many years. He was paid £12 cash for an evening’s work at The Basement.

[14] In December 1978 Fan Club played at The Art School Basement, supported by Devil’s Dykes.

[15] Alan Williams (see above) suggests that the Health & Safety regulations today would have probably set the maximum of [missing figure]

[16] Addison Cresswell, interview with the author, 10 September, 2008.

[17] Colin Matthews, was a music promoter, technician and, latterly, University Gallery and Theatre Manager until his retirement from the University of Brighton in 2008.

[18] E-mail to The Bunnymen Concert Log 1978-79, www.angelfire.com/wy2/setlists/

[19] Other bands put on in this era included post-punk and alternative dance band A Certain Ratio, Rip, Rig & Panic formed in 1980 (including two members of the radical anti Thatcher band, The Pop Group), and Scottish punk band Orange Juice.

[20] Addison, interview with the author, 10 September 2008.

[21] This was a provocative and highly controversial band involving Genesis P Orridge, performing in the Sallis Benney Theatre in February 1977. The concert was recorded and issued on their The Second Report debut album. They appeared again in 1978. Their live performances also involved visuals and often included reference to pornography and Nazi concentration camps.

[22] This Manchester new wave band were yet another band put on at Brighton Polytechnic that were featured on the John Peel Sessions on Radio !.

[23] ‘Smelly’, Sticky Floors and Sweaty Walls: The Book of the Basement, Brighton: University of Brighton Students Union, 1996, p.20.

[24] Interviewed by the author on 16 September, 2008

[25] Interviewed by the author on 3 September 2008.

[26] As above.

[27] Nicolette Burns, interviewed by the author on 17 September 2008.

[28] Interviewed by the author on 23 September 2008. Dean has been a stalwart on the Brighton music scene.

[29] These offices were also occupied by Harvey Goldsmith, another Brighton Polytechnic student from outside the Faculty involved with promotions, now one of the biggest names in events promotion.

[30] Who later recorded as Grab Grab Haddock.

[31] Gavin Hodge, ‘Fried eggs and HP sauce, please: Britain’s top caffs’, The Observer, 13 June.