The Fetishization and Objectification of the Female Body in Victorian Culture

Hannah Aspinall

Aspinall herein elucidates the sexual politics of the representations of the female body in Victorian literature, providing a social context that enriches understanding of the writings of the Brontë sisters, Elizabeth Gaskell and Mary Braddon. Victorian sexuality is explored in the Foucauldian sense; as something very much present in the power relationships of the time.

The Victorian age was one of great change largely brought about by the industrial revolution and the ‘historical changes that characterized the Victorian period motivated discussion and argument about the nature and role of woman — what the Victorians called "The Woman Question."’ Female writers were able to partake in discourse on their gender and writers such as the Brontes, Elizabeth Gaskell and Mary Braddon were challenging conventions as to what constituted decent female behaviour in literature. Their inclusion of passionate heroines into their texts was controversial, the wider, ‘respectable’ public were offended by these ardent females who disregarded the traditional idea of ‘femininity’. By modern standards novels such as The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Ruth and Lady Audley’s Secret, are considered to be relatively modest in their sexual content. However, for the Victorian period this was as passionate as literature could be and still be allowed to circulate publicly, due to the moral and social codes and the Obscene Publications Act of 1857.

Although this was a time when the rights and opportunities for women were expanding, their representation by males was often contradictory to the increased freedom they were experiencing. The female body has long been idealised, objectified and fetishized and this can be seen particularly in Victorian culture. Social rules and guidelines on how the female body should look, and how it should be dressed, objectified the body and encoded femininity within these rules. This made the portrayal of the female body a space for expression, ‘oppression and sexual commodification.’

A woman’s long hair, after all, is the emblem of her femininity. More than that, it is a symbol of her sexuality, and the longer, thicker and more wanton the tresses, the more passionate the heart beneath them is assumed to be [...] Images of ‘wanton’ tresses abound in Pre-Raphaelite art of the time, and are frequently seen in works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Rossetti was a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a movement that challenged ‘the Academy-based training with a vision that looked back to medieval and early-Italian art for inspiration’ and held the ‘aspiration to be true to nature and moral in content.’ This morality can be seen in the image of the ‘fallen woman’ that Rossetti depicts in many of his paintings. The ‘fallen woman’ is an ideological construct that acts as a direct opposite to the chaste and feminine ‘angel in the house’; the term could cover any woman that did not fit the rigorous moral standards of domestic normality.

Fig. 1. Lady Lilith by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The painting, Lady Lilith, by Rossetti is an exemplary piece for the representation of a ‘fallen woman’, in this case taking the incarnation of the femme fatale: ‘Engrossed in her own beauty, Lilith combs her lustrous, long, golden hair. Legendarily the first wife of Adam, her expression is cold, but her body voluptuously inviting.’ The picture of Lady Audley depicted in the sensation novel Lady Audley’s Secret, by Mary Braddon, echoes this cold and seductive painting: ‘No one but a pre-Raphaelite would have painted, hair by hair, those feathery masses of ringlets [...] my lady, in his portrait of her, had the aspect of the beautiful fiend.’

I've lived with the family forty-nine year come Michaelmas, and I'll not see it disgraced by any one's fine long curls. Sit down and let me snip off your hair, and let me see you sham decently in a widow's cap to-morrow, or I'll leave the house.

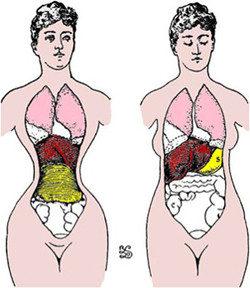

It is this link to self-regulation that led people to see the corset as the ultimate symbol, and indeed instrument, of female oppression. In Victorian Britain, the male and female spheres were polarized between the working male and the domestic female and these roles are furthered by the ‘obvious definitions made by dress.’ Groups such as the Rational Dress Society (1881) advocated a move away from the restricted and restricting female fashions that enslaved their wearer into delicate femininity, yet no real progress was made until a considerable amount of time after this point. However, questions were raised about the role and implications of ‘this lowly piece of underwear’ and debate upon the topic ‘burned steadily throughout the nineteenth century.’

The corset could be seen as a garment of conflicting morals; on the one hand it created the fashionable silhouette that marked out the wearer as a delicate, feminine creature and on the other hand, the lady that denied the corset was often tarred with charges of ‘sexual promiscuity or moral laxity’ – which led to the use of the term ‘loose morals’, referring to their lack of corset. Although corsets deemed the wearer to be the ideal of demure femininity, it conversely also had the effect of emphasising two erogenous zones: pushing up the breasts and flaring out over the hips and genital area. In fact, the pressure that the diaphragm and chest underwent due to the shape of the corset created the ‘peculiarly feminine heaving of bosoms so lovingly described in popular novels.’ This enhancement of feminine sexuality can also be seen in the connotations that having a slender, delicate waist would have. A slender waist suggests that the woman has not borne children yet, implying virginity and pureness – and the virginal female was idealised by Victorian men.

The arguments for and against tight lacing raged in the pages of the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine between 1867 and 1874; they were reputedly sent in by tight lacers themselves, women opposing tight lacing, ‘doctors and dress reformers [...].’ However, many of these letters were written with a ‘pronounced sadomasochistic tone’ which suggests that these prurient letters may have been fraudulent and say ‘more about the obsessions of its devotees and its opponents than about actual practice.’

In 1857, William Acton stated that ‘Prostitution is now eating into the heart’ of Victorian society. The prostitute is the ‘fallen woman’ personified, often pushed into this profession through the inability to gain work, poverty and circumstance, she is made into a social and moral pariah by society. However, whilst the prostitute was seen as morally depraved, for the Victorian man the use of prostitutes was widely acknowledged as a way to vent their animalistic sexual desires that they would not be able to express with their chaste wives. This double standard can be seen through the passing of the Contagious Diseases Act in 1864, and its amendments in 1866 and 1869. The act ‘legalised prostitution but entailed legislation enabling police to arrest woman suspected of being prostitutes and the subsequent examination of them for signs of venereal disease’, it was hoped that by controlling the prostitutes the spread of disease would be slowed, yet no measures were put in place to inspect or chastise the man.

In light of the focus on prostitution in the Victorian period, it is perhaps unsurprising then that the female genitalia was likened to a metaphorical ‘purse’ as for the prostitute, it was the lure of the vagina that was proffered as bait to potential customers rather than the proverbial beggars hat. This slang word also correlates to the literal and euphemistic meanings of the word ‘spending’. In the first sense the man who pays for the prostitute literally spends money on sexual intercourse, and in the latter sense ‘spending’ was a term for orgasm and ejaculation. For the two euphemistic terms the fact that the man is dropping his payment into the purse of the prostitute remains true.

In the poem Jenny, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as the narrator describes the sleeping woman, the ‘purse’ metaphor is used throughout. His cold and misogynistic view towards her is seen when he muses:

He believes that she is a prostitute purely to become rich – disregarding the fact that she may only be in this situation because she has no other choice. However, Robin Sheets suggests that ‘given the association between purses and female genitalia, the young man's account of Jenny's fantasies probably represents a displacement of his own.’

Furthermore, the use of the euphemistic ‘purse’ can be seen in the vitally important text Fanny Hill. Considered to be one of the first pornographic texts, Fanny Hill was actually published mid-eighteenth century, yet it is such an important text in the discourse of sexuality because it was ‘revolutionary in its open message to enjoy sex and sexuality [...].’ The novel is important due to the controversy it sparked that crossed over the centuries; cataloguer of pornographical material, Henry Spencer Ashbee listed twenty prohibited editions of the book between 1749 and 1845 alone. In a typically voyeuristic scene, the reader garners a graphic view of the character Mrs Brown’s genitalia.

The Victorian age marked the era when pornography became an industry as the ability for mass printing meant that pornography could be made widely available. The Obscene Publications Act of 1857 made distributing this material harder, yet it did not stop the flood, it merely pushed it underground. Of the many sexual practises portrayed in pornographical material, there is one that became so prolific in England that it became known as ‘Le Vice Anglais’ (the English Vice): the act of flagellation. Although flagellation stems from religious penance, it became entangled with sexual desire and flagellomania was rife in the Victorian era. The significance that flagellomania had can be seen in the existence of flagellation brothels where customers could pay to undertake a flogging for sexual gratification. One brothel in particular held a reputation for flagellation: the brothel belonging to Theresa Berkley. Berkley created a special apparatus, named the Berkley Horse, to assist the flagellation of her customers.

Flogging was not only important in the sexual sense as the issue was also discussed in relation to the ostensibly non-sexual flogging of children for punishment. However, similar to the issue of tight lacing, the discussions within the public forums, such as the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine and the Family Herald, were often originating from ‘prurient or [...] questionable motives.’ These spurious letters were sadomasochistic and pornographic in tone and were often related to the punitive nature of girl’s boarding schools.

The idea of the boarding school as an arena for flagellation and punishment can be seen in the flagellatory story The Mysteries of Verbena House. At last the bottom of the Bellasis was really exposed to view. It was a real perfect posterior. It swelled out grandly, properly, and gradually from a sloping small of the back that would have satisfied a Grecian sculptor. There were two lovely dimples just above the top and below a couple of sharply-defined creases, caused by the over powering swelling of the hemispheres, now that the thighs were tightly pressed together. [...] They showed health by their hardness, and terror by the goose-flesh look they had [...] It was a regal bum, yet tough withal. One that would take a fair amount of punishment [...].

Important here is the portrayal of the Victorian female bottom in flagellatory literature. Pornography was based on the pleasures and sensations of the body, as opposed to the realm of the mind seen in Victorian high art. The Victorian age was also concerned with the cataloguing of bodily parts and, disguised as it was by layers of petticoats or crinolines, the female bottom became a shining beacon for flagellation fetishists.

The Erotic Ankle: The Myth of the Sexualised Piano Leg

The Victorian era has often been termed as repressed both socially and sexually, however this is clearly not the case and the myth of the covered piano legs is metonymic of this fact. The traditional view of Victorian sexuality is that they ‘were so afraid of the power of sexuality that they felt compelled to cover up the legs of their pianos; they obscured signs of the body even where they existed only by inference.’ Certainly the strict dress codes of the time denote that female legs and ankles remain covered under swathes of fabric and to bare them is considered wholly indecent. Yet the idea that the Victorians covered the legs of their pianos as they were too provocative and evocative of the hidden female form is a common misconception.

Acton, William, Prostitution considered in its moral, social, and sanitary aspects (London: John Churchill, 1857)

Acton, William, The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs in Childhood, Youth, Adult Age, and Advanced Life: Considered in their Physiological, Social, and Moral Relations Access date 11th May 2012

Auerbach, Nina, ‘The Rise of the Fallen Woman’, in Nineteenth Century Fiction, 35 (1), (1980) Access date 10th May 2012

‘Background’, in Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource (Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery) Access date 10th May 2012

Bayles Kortsch, Christine, Dress Culture in Late Victorian Women’s Fiction: Literacy, Textiles and Activism (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009)

Bayles Kortsch, Christine, Dress Culture in Late Victorian Women’s Fiction: Literacy, Textiles and Activism (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009)

Berry Lord, William, The Corset and the Crinoline - A Book of Modes and Costumes from Remote Periods to the Present Time Access date 21st May 2012

Bloch, Ewan, The Sexual Life of our Time: In its Relations to Modern Civilization, Access date 21st May 2012

Bouleau, ‘Experimental Lecture by Colonel Spanker’, The Birch Grove (2010) Access date 21st May 2012

Braddon, Mary Elizabeth, Lady Audley’s Secret (London: Atlantic Books, 2009)

Brayfield, Celia, ‘A Lifestyle Haircut’, in The Times (12:00AM, July 20 2004) Access date: 10th May 2012

Cleland, John, Fanny Hill (London: Penguin, 1985)

Cooper, WM. M., Flagellation and the Flagellants: A History of the Rod in all Countries from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (London: John Camden Hotten, 1869)

Cunningham, Patricia A., Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850 – 1920: Politics, health, and art (Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2003)

Etonensis, The Mysteries of Verbena House; or, Miss Bellasis Birched for Thieving. (Birchgrove Press, 2011)

Gaskell, Elizabeth, Ruth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011)

Gitter, Elisabeth G., ‘The Power of Women's Hair in the Victorian Imagination’, in Modern Language Association, 99 (5) (1984), Access date 21st April 2012

Klingerman, Katherine Marie, Binding Feminity: An Examination of the Effects of Tightlacing on the Female Pelvis (Vermont: University of Vermont, 2004) Access date 8th May 2012

Krugovoy Silver, Anna, Victorian Literature and the Anorexic Body (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004)

Marcus, Stephen, The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid-Nineteenth Century England (New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2009)

Matus, Jill L., Unstable Bodies: Victorian Representations of Sexuality and Maternity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995)

Moller, Kate, Rossetti, Religion, and Women: Spirituality Through Feminine Beauty (2004) Access date 10th May 2012

Nagle, Christopher, ‘Sterne, Shelley, and Sensibility’s Pleasures of Proximity’, in ELH, 70 (3) (2003) Access date 8th May 2012

Ofek, Galia, Representations of Hair in Victorian Literature and Culture (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009)

Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource, Background (Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery) Access date 10th May 2012

Roberts, Helene E., ‘The Exquisite Slave: The Role of Clothes in the Making of the Victorian Woman’, in Signs, 2 (3) (1977) Access date 9th May 2012

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel, ‘Jenny’, in Poems (London: F.S. Ellis, 1871)

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel, Lady Lilith, Access date 21st May 2012

Shaw, Rhianna, The Great Social Evil: “The Harlot’s House” and Prostitutes in Victorian London (Brown University, 2010) Access date 11th May 2012

Sheets, Robin, ‘Pornography and Art: The Case of ‘Jenny’’, in Critical Inquiry, 14 (2), (1988) Access date 8th May 2012

Steele, Valerie, Fetish: Fashion, Sex and Power (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996)

Sweet, Matthew, Inventing the Victorians (London: Faber and Faber, 2001)

Wagner, Peter, ‘Introduction’, in John Cleland, Fanny Hill (London: Penguin, 1985)

‘The Woman Question: Overview’, The Norton Anthology of English Literature Access date 19th May 2012