Image: The Arts terracotta panel from the main facade of the 1877 building in Grand Parade. It was, with its scientific counterpart, designed by Alexander Fisher, manufacured by Messrs Johnson, Ditchling, 1877. These can be seen in situ in the Faculty of Arts Grand Parade foyer.

Image: The Arts terracotta panel from the main facade of the 1877 building in Grand Parade. It was, with its scientific counterpart, designed by Alexander Fisher, manufacured by Messrs Johnson, Ditchling, 1877. These can be seen in situ in the Faculty of Arts Grand Parade foyer.Chapter text, Jonathan M Woodham

Deliberations about the nature and purpose of art and design education in Britain were aired increasingly in the second half of the eighteenth century with the involvement of bodies such as the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA). Founded in 1754, it held its first exhibition of contemporary art in 1760 and first industrial exhibition in 1761. However, as the impact of manufacturing on a significant scale became increasingly widespread, in the face of growing economic competition from in Europe in the early decades of the nineteenth century attention moved from the technical to the aesthetic quality of British manufactured products. British goods were increasingly perceived to be lagging behind their continental competitors in terms of design, resulting in greater attention being paid to the provision and delivery of art and design education in Britain as a potential means of redressing such shortcomings. As a consequence, debates focussed on the national importance of art education gathered pace during the 1830s, boosted considerably by the publication of the 1835 Parliamentary Select Committee’s Report on Arts & Manufactures and the ensuing establishment of the Government School of Design in Somerset House, London, in 1837. Also noteworthy in this context was the 1849 Select Committee’s Report on the School of Design. All of these considerations provided the impetus that was to result in the establishment of the Brighton School of Art.

In the decades immediately after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, there was increasing activity in the realm of adult education in Brighton. An important figure in this movement was John Cordy Burrows, a surgeon and local politician who went on to become Mayor of Brighton three times and receive a knighthood. Having moved to Brighton in 1837, he soon became closely involved in a number of philanthropic and educational initiatives in the town, including the founding of the Literary and Scientific Institution in 1841 and the establishment of the Brighton Mechanics Institution, for which he was Secretary from 1841 to 1857. He also brought about a number of aesthetic and sanitary improvements in the municipality, but perhaps of most significance in the context of art education in Brighton was his membership of the Town Committee that bought the Royal Pavilion from the Commissioners of Woods and Forests for £53,000 in 1849. The Pavilion was to provide the first premises for Brighton School of Art ten years later.

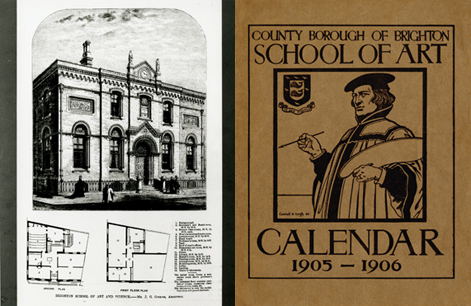

Image: John L. Gibbins design for the Brighton School of Art, Grand Parade, from The Builder, 1977 and Brighton School of Art Calendar 1905-1906

Image: John L. Gibbins design for the Brighton School of Art, Grand Parade, from The Builder, 1977 and Brighton School of Art Calendar 1905-1906Incipient ideas for the establishment of a School of Art in Brighton came to a head in August of 1858 when a public meeting was called in the Town Hall to air the possibilities. This resulted in the formation of a Committee to raise subscriptions and donations under the chairmanship of Dr John Griffith. Very much in line with wider national debates, the Committee defined their aims in the following terms:

The grand object is to instruct working people to do their work better by turning it out of hand neatly and handsomely as well as usefully, and thus enable them to command the best price for their labour, and to compete more successfully with the foreign workman, who, in these days, when the public require some sort of ornament and elegance about the commonest article, in many cases beats the English workman out of the market.

Most of the art schools that had already been established throughout Britain in the 1840s and 1850s had been linked to local and regional industries such as pottery, glass, textiles, furniture making, carpet weaving, lace making or textiles. Brighton was not an industrial centre in the most obvious sense but, according to the Victorian art and design education tsar Henry Cole on a later visit to Brighton, her ‘industries’ were ‘health, recreation, education and pleasure’. (DJ3) (DJ1)

Only four months after the August 1858 public meeting, on Monday 17 January 1859 Brighton School of Art opened its doors to more than fifty pupils and was situated in a room off the Kitchen provided by the Town Council at a rent of £26 per annum. The first Art Master was John White who brought with him experience of a similar post at Leeds School of Practical Art, as well as certification as a Teacher of Drawing and Painting from the Department of Science and Art. He had also attended the Central School for the Training of Art Teachers in London. At this early stage of Art School life at Brighton, John White ran classes for several different constituencies: those of independent means who attended the Day Classes and were segregated by gender; artisans who were provided with evening classes at a low fee rate; and teachers, for whom fees were lower still.

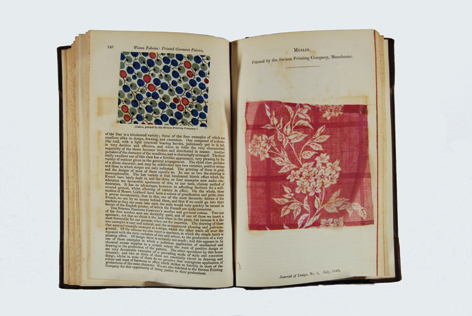

Image: The Journal of Design (1849-1852). Edited by Henry Cole and his associate Richard Redgrave, the purpose of this periodical was to promote public, particularly middle-class, taste and improve industrial design. Its appeal was enhanced by the inclusion of attractive samples of wallpaper and textile design. (University of Brighton Design Archives). Photo: Barbara Taylor

Image: The Journal of Design (1849-1852). Edited by Henry Cole and his associate Richard Redgrave, the purpose of this periodical was to promote public, particularly middle-class, taste and improve industrial design. Its appeal was enhanced by the inclusion of attractive samples of wallpaper and textile design. (University of Brighton Design Archives). Photo: Barbara TaylorIt has proved difficult to unearth the First Annual Report (1859), with the consequence that a range of detailed information is limited for that year. However, the Second Annual Report for 1860 provides an illuminating overview of the School’s student profile, accommodation, finances and public presence, a picture that largely typifies developments at the Brighton School of Art in the eighteen years leading up to its move to purpose-built premises in Grand Parade, Brighton, in 1877.

Clearly, the first year had witnessed a number of teething problems as evidenced by a public meeting held on 21 January 1860, little more than a year after the School first opened, and at which the institution was constituted on a formal basis. The composition of the student body was clearly a bone of contention as a motion was proposed ‘to confine the operations of the School to the artisan classes’. This was strongly opposed by the School Committee which was of the view that their institution should be open to all classes, commenting that ‘without the fees paid by the wealthier classes it would be impossible to extend the benefits of this School to the large numbers who receive almost gratuitous instruction from the Art Master’.

In 1860 there 58 students attending the fee-paying Day Classes: 17 gentlemen and 41 ladies. 167 attended the Evening Classes: 99 artisans, 8 schoolmasters and male pupil teachers and 60 schoolmistress and female pupil teachers. However, John White’s responsibilities also covered national and public schools: including 46 pupils from Chichester, these numbered 816, with the grand total of all students amounting to 1041. Drawn from the community, artisans were of considerable importance to the School and remained so until the mid-1970s when the then Brighton Polytechnic (of which the School of Art was a founding constituent) transferred almost all of the trade courses to Brighton Technical College. In 1860, the artisans registered for classes at the School numbered 17 joiners and carpenters, 16 assistants to architects, builders, drapers and others, 5 engravers, 4 masons, 3 cabinet makers, 3 carvers, 3 printers, 2 millwrights, 1 pastry cook, 1 silversmith and 1 mechanical dentist. This wide range of professions proved to be in line with the findings of the Select Committee Report on the School of Art of 1864.

During 1860 - out of class hours and in the summer vacations, four days a week from 10.00am until 4.00pm - the School was open for study by students of the School, free of charge. In line with the Committee’s commitment to make the School as widely accessible as possible, this opportunity was taken up by a large number of students and was soon extended to artisans and teachers. Other members of the public could also take up the offer on payment of 2 shillings per month, 8 shillings per session, or 15 shillings per year.

Problems of space reared their head in 1860, a feature that was to reappear regularly through much of the rest of the institution’s history. The municipal authorities, effectively the School’s landlords, allocated two new rooms to the School in the South-West corner of the Pavilion since it had given over the room originally allocated to the School to allow an exhibition of paintings for local artists. However, the new rooms proved quite inadequate for the numbers of students and led to a slump in artisan numbers for evening classes. This was considered ‘bad publicity and bad for morale’ and, as a result, the School of Art regained its original premises from the Town Council in January, 1861.

In December 1860 the Second Annual Examinations of students and others were reported as ‘far surpassing those of last year’. The Department of Science and Art in London, a powerful body that had centralised control of teachers and the curriculum, oversaw these competitive examinations that, if successfully undertaken, resulted in the award of certificates, books and medals. In 1860, 15 students were felt to be worthy of local medals, although the regulations only permitted a total of 11, whilst 7 were “deemed worthy of being sent to compete for National Medallions”. The Second Annual Report (1860) commented that

The results of the examination afford a strong testimony to the abilities of the Art Master, Mr John White, who has been efficiently seconded by the Art Pupil Teacher, Mr Farncombe.

Indeed, White was given further praise in a letter of 8 February from Norman Macleod, Assistant Secretary of the Committee of the Council on Education at the Department of Science and Art in South Kensington.

Perhaps the last major characteristic to be drawn from the Second Annual Report 1860 was the fact that an exhibition of almost 100 drawings and paintings, composed of works that had received medallions or an honourable mention in the National Competition, was displayed in the School of Art premises, attracting several hundred visitors during its run of some weeks. These annual shows became a regular feature of the Art School year, marking out a tradition that has evolved into the present day, often-flamboyant Degree Shows that take place annually in the Faculty of Arts & Architecture in Grand Parade at the end of the Summer Term.

John White’s term as Art Master continued over the next few years although, for a period during the 1860s, there were tensions between the Art School and the Department of Science and Art in London. Henry Cole was staying in Brighton in late 1867 and talked things over with the management Committee of the School of Arts. The issues were resolved, following a public meting at which a Mr Bowles from the Department explained the ways in which new policies would be advantageous to Brighton. These were adopted by the Committee and it was resolved that the School would enter for the examination in March 1869. Nonetheless, the rift between the centralised authority in London and practice at Brighton resulted in a temporary discontinuance of the Government Grant. This, in turn, led to the loss of Mr Farncombe, the Art Pupil Teacher, although a Mr Maurice Adams, ‘long a Student in the School, replaced him.’

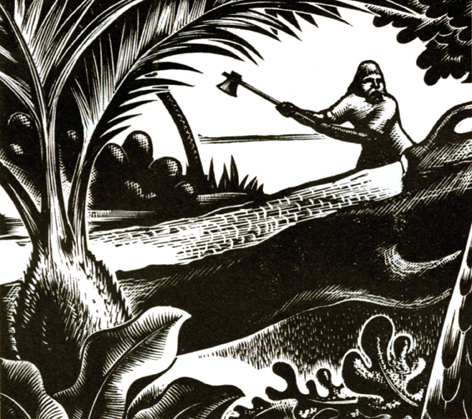

Image: John Biggs, Illustration from Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, Penguin Illustrated Classics 1938

Image: John Biggs, Illustration from Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, Penguin Illustrated Classics 1938 Following the death of John White in 1871, Alexander Fisher was appointed as Art Master. Like his predecessor, he was trained in South Kensington but also brought with him a qualification in building. His early tenure was marked by a dramatic increase in numbers, almost 50% in three years, This may have been partly influenced by a steady increase in the number of prize winners in the National Examinations, including a National Bronze Medal in 1873 and a National Silver Medal for a crayon drawing from the antique by Miss E L Black in 1874. (077a) (075a) Whatever the case, the accommodation was clearly insufficient to deal with such numbers. As was remarked in the 1874 Annual Report:

The present accommodation is entirely inadequate to the requirements of the Pupils now under instruction and applications for instruction have often to be refused. Your Committee are therefore glad to be able to congratulate the subscribers upon the prospect now offered of a suitable School Building being ere long erected.

The final sentence of this quotation referred to the fact that, in September 1873, the Mayor and a number of leading citizens had formed a fund-raising committee to provide the School with a new building. Problems about locating an appropriate site came to the fore: one early ambition had been to situate the new School opposite the Public Library and Museum, but this proved problematic and attention then shifted to finding a site on the Stanford Estate. However, the School’s Management Committee felt that a central location was essential and eventually, in 1875, a site in Grand Parade was secured. This was seen to be not too far from the railway station, as well as being well-placed to attract its intended mixed constituency of independent fee-paying students through the proximity of private schools as well as housing of both the professional classes and working classes. In January 1875, a provisional contract for the erection of the new School of Art was approved and, in the following months, Alexander Fisher advised the Building Committee about the requirements for the building and the drawing up of instructions to architects. On 27 July, John L Gibbins’ design was selected from ten proposals that had been received following advertisement. By early January 1876 the plans for the complete building were passed,having been drawn up in line with the guidelines that the that the Department of Science and Art had issued in 1859.

Gibbins, a local professional architect, was formally appointed, tenders for the building were put and won by a Mr Lockyer at a cost of £6,150, and the building erected through the generosity of a Captain Hill who lent £5000 at 4.5%. The importance of this loan should not be underestimated since the maximum that the Department of Art and Science in London would contribute to towards the project was £500, providing that qualified staff delivered the courses.

It was perhaps fitting that on 9 June 1876 Henry Cole, the central figure in British art and design education between 1852 and 1873, should lay the foundation stone for the new Brighton School. As has been seen earlier in his design reforming Journal of Design, Cole was far more than an educational bureaucrat, having been a Royal Society of Arts design prize-winner of a teapot that was successfully put into mass production by Minton in the late 1840s and a moving force behind the Great Exhibition of All Nations held in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park in 1851. At the 1876 foundation-laying ceremony Cole stated that he felt that, in terms of art education, Brighton had fallen behind other towns in the region with smaller populations, largely due to the fact that the existing premises occupied by the School of Art were not fit for purpose. In 1871 Brighton’s population stood at 103,000 but the School had only 173 students, whereas Croydon had 70,000 inhabitants and 200 students, and Southampton had 55,000 inhabitants and 260 students.

The new Brighton School of Science and Art was built in a modern Romanesque style, with the façade in brick with Bath stone coping and cornices. (SPH2) The columns flanking the main entrance were in polished red granite, those in the windows in red Mansfield stone, with the façade enriched by a series of terracotta panels and lunettes that had been designed by the Art Master Alexander Fisher, and executed by Messrs Johnson at the nearby Ditchling Pottery Workshop. The two main terracotta panels (Christmas Card idea) can be viewed in the present day entrance foyer of the Faculty of Arts and Architecture in Grand Parade, Brighton. Their main subject matter symbolically represented the activities of the new School, as was recounted in the Brighton Herald of 3 February, 1877:

The northern wing has a panel, with figures in alti relievi, symbolical of the Arts. Thus pottery is represented by a boy carrying an earthen vessel; Architecture, by another constructing a toy-house, Sculpture, by a sculptor at work on a bust; Geometry by a fourth figure examining a scroll; Building Construction, by a youth with a saw and a plank; Painting, by an artist at his easel, and so on…It says much for the artistic genius of Mr Alexander Fisher, the Head Master, who furnished designs for the decorations, that appropriate emblems have been given to each of the various figures.

In fact the School’s relationship with Messrs Johnson provided an early collaboration with local industry, as the firm offered an annual prize of £10 foe the best work in modelling. As a reporter in the Sussex Daily News commented:

It will be a striking testimony to the value of the School if, in addition to the advantages it offers to existing trades and manufactures, it should prove the means of developing a new local industry which admits of the application of art in some of its highest forms. The raw material for this industry exists in the best quality in the neighbourhood of Brighton, at and near Ditchling, having excellent communications with the metropolis, which is the great market of wares of this description.

The ground floor of the new School of Science and Art was devoted to Administration and Science, for which the School was well-equipped in terms of equipment and two rooms (including a tiered lecture room) for lectures in ‘Chemistry, Steam, Electricity Magnetism, Optics, Acoustics and other branches of Physics and Mathematics’. Alexander Fisher also contributed to this aspect of the curriculum with a series of lectures on mathematics. Prior to this period, the only science that had been taught in the School was closely related to art studies.

The first floor was devoted to art and consisted of a number of rooms including the Elementary Room. This was top-lit, measured 38 feel by 32 feet, and was where pupils were seated at long desks on long benches, copying exemplars borrowed from the National Art Training School in South Kensington, thereby adhering to the tightly structured Course of Instruction laid down by the Department of Science and Art. The same room was used for classes in Building Construction (with blackboard demonstrations). The Painting Room, also lit from above, contained of many celebrated antique busts and classical sculptures and was used only by advanced student and ladies’ classes.

On 3 February 1877, the new School was opened amidst great municipal celebrations and rejoicing (BSA44). Princess Louise, the most artistic of Queen Victoria’s children, and a highly appropriate choice for such an event, played a leading role. Often entertaining leading contemporary artists at Kensington Palace, she was an accomplished sculptor in her own right. In 1872, She was also the co-founder and President of the Union of Higher Education of Women. Almost inevitably, another major presence at the opening ceremony was the Victorian art educational tsar, Sir Henry Cole.

Having arrived at Brighton Station, Princess Louise swept through the town in an open topped carriage, accompanied by a detachment of the 20th Hussars, the route taking in a triple Arc de Triomphe proclaiming welcome to the lovers of Science and Art at the junction of Queen’s Road and North Street. (SPH3) (SPH6) After inspecting the new School the Royal Party went on to the nearby Dome for the official ceremony. In his inaugural speech, Princess Louise’s husband, the Marquis of Lorne, drew attention once more to the economic importance of education in science and art as a means of competing successfully with foreign manufacturers. He also expressed the hope that the British

…must ever remain in the centre of trade, placed as we are in the ocean between many great countries. The course of trade should always sweep past us. Make the best use of Science and Art, and cultivate both in all manners of manufacture, as well as durability. You may say what occasion have we to fear, for no other nation can compete with us in such respects. But, believe me, you will find some very strong competitors among European nations.

In 1877 the School staff comprised the Head Art Master, Alexander Fisher, the Second Master William M Alderton, two qualified Assistants, Mr H P Gill and Miss H E Grace, and two Science Masters, a Mathematics Master and a Teacher of the Theory of Music. Miss Grace was a graduate of the Royal Academy Schools and H P Gill had been a student at Brighton. Perhaps boosted by the new purpose-built accommodation and the sense of optimism that this must have engendered, at Christmas 1877 members and past members of the School, Miss H E Grace and Mr H E Ward, were Silver Medallists at the Royal Academy of Arts. At the same time, Miss E Knight and Mr George Ruff, whose work is illustrated in this chapter, passed the entrance competition for the Schools of the Royal Academy and, in March of the following year, Mr H P Gill, mentioned above, won a scholarship to the Art Training School at South Kensington. Later on, in 1878, the number of prizes and distinctions awarded to Brighton students by the Department of Science and Art ‘far exceeded the results of previous years’: for the first time a National Gold Medal, in conjunction with a Princess of Wales Scholarship, was awarded to Miss Frances E Grace. (078a)

There were many public showings of students’ work during these years, some of which were very elaborate affairs. On 8 January 1883, for example, a Soirée was held in the Royal Pavilion attended by more that 1,200, having been organised in conjunction with an Exhibition of Students’ Paintings and Studies in the Masonic Rooms. Entertainment at the nearby Dome included two concerts under the baton of Mr A King, teacher of Music at the School, as well as an Amateur Dramatic Performance, Tableaux Vivants and Ghost Illusions. Past and present students and members of staff performed all of the latter. (345a)

The linking of art and science highlighted in the Marquis of Lorne’s 1877 inauguration speech for the new School was also reflected more widely. In the later years of the century many felt that Britain’s lack of progress by comparison with her leading industrial competitors could be placed at the door of inadequate education in the scientific and educational fields. A number of Commissions were set up to address this and related issues, including the 1881-84 Samuelson Royal Commission on Technical Education. The fact that art education was becoming so dominated by the fine arts was also noted in the ensuing report of 1884; it also commented about the lack of first initiated under the Board of Trade in 1837.

The Technical Instruction Act of 1889 allowed local authorities to form Technical Instruction Committees, to levy rates in order to raise the standard of art and science education for artisans and, as a consequence, ally themselves more closely to local industry through education. At this time the Brighton School of Science and Art was still under the control of its Board of Trustees and Advisory Committee and was dependent on student fee income, local subscriptions and the modest grant income from the Department of Science and Art. However, new funding opportunities emerged in 1893 when the residue grant was given over to the County and Borough Councils and the School’s Trustees and Committee passed the School over to the County Borough Council as a gift.

Image: Women teachers and pupil teachers' drawing class, early 1900s. Art School Archive in the University Design Archives.

Image: Women teachers and pupil teachers' drawing class, early 1900s. Art School Archive in the University Design Archives.As a result of these new openings for local authorities, a new Municipal School of Science and Technology, designed by F C May, the Borough Surveyor and Engineer, was opened on 20 September, 1897. This allowed for an expansion of activities in the School in Grand Parade. By now, the School was flourishing under the aegis of the new Head Master, William Alderton, who had for some years been the Second Master under Alexander Fisher, having taken over as Head in 1892. The 1902 Education Act brought about a further change as Schools of Art were placed under the control of local education committees. This resulted in another significant shift in the ways in which teaching was directed. Ever since 1863 the Department of Science and Art had imposed a salary structure for art masters: the Payment by Results Scheme. As a result, payments to Schools of Art were largely conditioned by student successes in public examinations and the National Competition for Schools of Art. This was also very much how the press had measured success in this domain until the Scheme was finally abandoned in 1915. (BSA5)

William Bond, a former student at the School, became Head Master in 1905. His educational outlook was essentially a broadening one, responsive to the new opportunities afforded design and the arts and crafts, rather than the more restrictive outlook that was largely predicated on drawings for national competition. Bond was very much in tune with the progressive outlook of a number of important contemporary educators, particularly Walter Crane at the Royal College of Art (until 1896 the National Art Training Schools), William Lethaby at the Central School (established by the London County Council in 1896), and Francis Newbury at Glasgow School of Art (the new Charles Rennie Mackintosh building having opened in 1899). The Studio magazine was also an important mouthpiece for progressive developments in the arts and crafts and applied arts. Having commenced publication in 1893 it was avidly read in progressive design and applied arts circles across Europe. At Brighton before the First World War, the portfolio of courses at the School of Art included typography, silversmithing, jewellery, leatherwork, woodcarving, embroidery and lace making. (BSA6)

In 1913 when the Board of Education established its Teaching Certificate for Teachers in Schools of Art (renamed the Art Teachers Diploma in 1933), the School of Art enjoyed further opportunities to extend the range of its courses. In the following year, the School was recognised as one of the few centres outside London where such courses could be taught, leading to a grant increase from £800 to £1000. The Brighton Herald suggested this had been achieved, at least in part, by Brighton Education Committee’s commitment to greater expenditure on the School to keep the equipment up to date. In fact, by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the School appeared to be in a healthy state. One source commented in 1914 that

Apart from general excellence, three features are conspicuous – (1) the large e number of students who have passed through Brighton Training to take up responsible positions throughout the country and abroad; (2) the co-ordination of art instruction with the general life of the town; and (3) the close correlation of the instruction of the School of Art and other institutions under the authority.

The Chairman of the Brighton Municipal Art sub-committee gave further evidence of Brighton’s position in the wider national context when he stated that, judging by the amount of grant received, the School of Art was eighth out of the 16 principal Art Schools outside London, and first, in terms of grant and student numbers, south of London.

As has been described above, the early decades of the twentieth century were important for curriculum development alongside national and international debates about the wider role of design and economy, a significant undercurrent that had surfaced frequently since the 1830s. However, it was not merely the initiatives of Lethaby, Crane and Newbury that suggested new directions. In 1915, the Design and Industries and Industries Association (DIA) was established, a national non government-funded organisation that set out to establish stronger relationships between British designers and manufacturers. The DIA was never as radical or all embracing as its German counterpart, the Deutscher Werkbund (DWB), founded in 1907, that had inspired it. The DWB was an alliance between manufacturers, designers, educators, philosophers, politicians and others who recognised the economic significance of producing well-designed, high quality goods for export. A large-scale DWB exhibition was mounted in Cologne in 1914, where buildings by Walter Gropius (the future Director of the German Bauhaus) and others announced the advent of modernism and a distinct rupture with the historicising preoccupations of the Victorian era. Several leading British designers had visited the Cologne exhibition inspiring them to launch the DIA: Brighton School of Art was an early member of the DIA along with a handful of others – Bath, Bradford, Camberwell, Cork, Edinburgh, Huddersfield, Leicester, Ipswich, Nottingham and Woolwich.

The Head Master at Brighton, William H Bond, played an important role in promoting the aims of the DIA in the town, explaining its purpose to the Brighton and Hove Chamber of Commerce that gave approval to its aims and objectives in a meeting held in October 1915. Bond explained how Britain lagged behind her competitors such as Germany and America, claiming that the typographer ‘Edward Johnston was far better known in Germany than he was in England five years ago’. In his address to the Chamber, Bond also emphasised how progressive British furniture design ‘known only to a few’ had inspired the work of the Germans, as had the British education system. Also reflecting issues raised earlier in this chapter, Bond drew attention to the gulf between technical and art education in Britain.

Image: Students engaged with wood engraving, 1910s. Art School Archive in the University Design Archives

Image: Students engaged with wood engraving, 1910s. Art School Archive in the University Design Archives Material about the School of Art’s contribution to the First World War is relatively scarce, although there was a good deal of heated discussion in public fora about the place of art education at a time of hostilities. For example, it was reported that, on the occasion of the School’s Student Prize-giving of 1915, the Mayor of Brighton, Alderman J L Otter, surprised his audience when he spoke about the ‘futility’ of art studies at a time when

…. war engrosses the whole mind of the nation…Supposing you had in your school Benevenuto Cellini or Raphael. They could not save the slaughter of a single soldier or advance one fighting line a single inch.

However, the Chairman of Brighton’s Education Committee countered such a view by praising:

… the students of the school in the highest terms for the way in which they have kept to their work amid the anxieties of war. Such a school at the time is a real asset to the town. People are telling us that we are descending into barbarism under the pressure of the war spirit. Such an organisation as the Brighton School of Art is preserving us from that fate. It refuses to allow the finer aspects of life to be destroyed by the war spirit.

Also somewhat controversial was the position of Percy Horton, alumnus of the School of Art and later Master of Drawing at the Ruskin School of Art, Oxford (1949-64) who features on the individual pages of this book. Politicised from an early age (as was his brother Ronald), Percy had studied with distinction on a scholarship at the School between 1912 and 1916 and appeared in court in July 1916 charged with failing to report for military service. He argued to no avail that, as he was a genuine conscientious objector to war, conscription - which had been introduced in the same year - should not apply to him. He was, however, sentenced to two years hard labour.

Nonetheless, with the strong support of the Head Art Master, William Bond, the School of Art provided opportunities for a number of disabled soldiers at the Brighton Pavilion Hospital, offering training for such occupations as letter cutting in wood and stone, mechanical draughtsmanship, die-cutting and other related subjects that required instruction in industrial art. Princess Louise, who had become a patron of the School of Art on the occasion of the inauguration of the new School building in 1877, was interested in this work and visited the Hospital. These disabled soldiers studied from between 15 to 28 hours per week.

During the later stages of the First World War, Bond was concerned with the appearance of Brighton, reacting negatively to many aspects of the urban environment, a theme that a number of his British arts and crafts antecedents such as John Ruskin and William Morris had pursued with zeal. When addressing the Brighton Guild of Applied Art which, at a meeting in late March 1918, was discussing ideas about beautifying the town, Bond complained about the ‘gruesome horror’ of the New England Road railway arch and commented on plans to render it an ‘attractive entrance to the town’. Concern was also expressed that there should be much greater emphasis on cleanliness and tidiness in public spaces, particularly the railway station and its approaches. He also argued for the preservation of the ‘distinctive soul’ of Georgian Brighton and that the Town Council should desist from painting the Royal Pavilion ‘workhouse yellow’ as it represented the ‘last despairing cry of colour on its deathbed, and in its raucous tones some devilish influences might be traced’. Professor W R Lethaby of the Central School of Arts and Crafts, London, and a member of the DIA, served as one of the Vice-Presidents of the Brighton Guild of Applied Art.

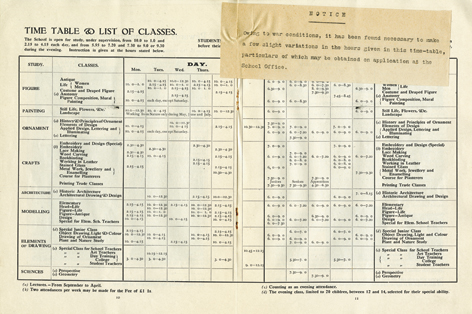

Image: Wartime weekly timetable, 1916. Art School Archive in the University Design Archives.

Image: Wartime weekly timetable, 1916. Art School Archive in the University Design Archives. Following the sudden death of William Bond in 1918, William Evans was appointed as the new Head Master of Art in the following year, having come from the Woolwich Polytechnic School of Arts to take up an annual salary of £500, rising by a series of 4 increments to £650. His responsibilities were considerable, as he was charged with overseeing art education in Brighton at elementary and secondary level. As was stated in the West Sussex Gazette in 1923:

The School of Art is probably unique among similar institutions of the country in that the Principal has complete control of the teaching in the various elementary and secondary schools of the town, ensuring co-relation between their work and subsequent studies at the “Art School”.

Like Bond before him, Evans sought to forge links between the School and the wider context of the town and its industries. Eight foremen who were working in various workshops in the town were employed to provide instruction in architecture, wood and stone carving, metalwork, enamelling, gold and silversmithing, jewellery, typography, lithography, house painting and decorating and sign writing. Classes from the art teachers at the School supplemented such vocationally focussed classes.

Image: Brighton staff and students in front of classical plaster casts for studying the human form. Art School Archive in the University Design Archives.

Image: Brighton staff and students in front of classical plaster casts for studying the human form. Art School Archive in the University Design Archives. W H Evans served as President of the National Society of Art Masters in 1924, a year in which its annual conference was held in Brighton School of Art. Key speakers were Harold Curwen of the Curwen Press and President-elect of the NSAM and Joseph Thorp of W H Smith, talking respectively on drawing for posters and printing and on art and the businessman. Both were keen members of the DIA and stressed the correlation between good design and good business, a cri de coeur that resounded through the decades via bodies such as the British Institute of Industrial Art, established in 1920, the Board of Trade’s Council for Art & Industry which began operating in 1934, and the Council for Industrial Design, formed in 1944 and, in a rather different way, in the emphasis placed on the creative and cultural industries in the decades on either side of the Millennium. In his 1924 Presidential Address, Evans suggested that, in terms of the relationship between art and industry, ‘the pendulum has swung too far in the direction of industrial art’. By this he meant that he believed that design education in particular was overly vocational and that there was a need for an educational system that acknowledged the importance of the liberal arts as a support for, and counterpart to, what were then termed the commercial arts (such as graphic design and advertising). This was an area of debate that continued in various ways throughout the interwar years, eventually coming to a head in the 1960s (See Chapters 4, 6 and 7).

In the following year, 1925, the President of the Federation of British Industries, Colonel Vernon Willey, spoke at the National Society of Art Masters conference at Leeds School of Art and argued strongly about the need to bring together ‘artistic design’ with the ‘country’s industries’. Although acknowledging British traditions of quality and durability in mass-produced goods, he felt strongly that ‘one must recognise that both business and culture are becoming daily more and more international and, in spite of our conservative instincts, we, as a nation, must, I think, learn to comply rather more than we have done with international demands’.

In fact, the work of Brighton School of Art performed well in the international arena, as evidenced by its showing at the 1925 Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, attended by more than 15 million visitors. Although the School had received its invitation to participate too late to prepare anything specifically for the exhibition (and thus for inclusion in the Exposition catalogue) the Daily Telegraph reported that it received a Diploma of Honour for technical instruction, a Gold Medal for technical instruction in ceramics, and Silver Medals for technical instruction in textiles and metal. More than 20 Schools of Art had been invited and Brighton gained far more awards than any other institution outside London, sweeping up 22% of those made to provincial art schools.

Evans was clearly well thought of in the wider art school world as he was headlined in an article in Drawing & Design in 1925 entitled ‘Famous Contemporary Art Masters: William H Evans ARCA and the Brighton School of Art’. It was reported there that the School of 25 members of staff and 600 students was so successful that there were plans being drawn up for an extension, although it was ‘to be hoped that these extensions will not disturb Mr Evans’ beloved school garden, an old world flower and water garden with stone walks and pergola, formerly used as a rubbish dump, but now a valuable ground for the study of trees, flowers, birds and fishes, and a splendid background for models of all kinds, which are posed out there in fine weather’.

Mural art was a field in which Brighton staff were widely recognised, bringing together the fine arts and interior design. A notable example of this was seen in the interiors of the Regent Cinema, Brighton, the first of the Provincial Cinematograph Theatres Ltd (PTC) ‘super cinemas’, seating 3000 and seen by the Times newspaper to ‘more nearly represent the American cinema theatre du luxe than any other building in this country’. Costing more than £400,000 and situated by the Clock Tower at the corner of Queen’s Road and London Road, its interiors included murals by Lawrence Preston of Brighton School of Art and Walter Bayes, Head of the Westminster School of Art. They worked closely with the Regent’s architect, Robert Atkinson, with Preston executing elaborate designs for the proscenium arch. Overall, the scheme was viewed as “possibly the most extensive and successful attempts to beautify a picture theatre undertaken so far in England’. Lawrence Preston’s other mural schemes included his First World War mural at St Luke’s School, Brighton, restored in 2007 after a £30,000 fund-raising campaign. Dorothy Sawyers, another member of staff at the School and described in 1925 as ‘perhaps the most brilliant decorative painter in the school’, was also widely known as a muralist who worked on cinema schemes.

Louis Ginnett, another well-known painter on the School staff, carried out another extensive mural scheme, executed between 1913 and 1939 at the then Brighton, Hove and Sussex Grammar School (now Sixth Form College). Claire Willsden, in her book on Mural Painting in Britain 1840-1940: Image and Meaning (2005) commented that:

The scheme as unveiled in 1939 as The History of Man in Sussex and whilst superficially a sequence of well designed and realistic evocations of historical events which contribute to the making of Britain’s Empire, such as `After the Armada, it also contains a distinctive scientific interpretation of the past which takes to its logical conclusion William Hole’s earlier inclusion of Stone Age warriors in his ‘Great Scots’ frieze at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and reflects contemporary archaeological discoveries.

Image: 'Rye, After The Armada', one of the Ginnett mural panels in the School Hall, Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College (BHASVIC) with kind permission of Mr Chris Thomson. Photo: Barbara Taylor

Image: 'Rye, After The Armada', one of the Ginnett mural panels in the School Hall, Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College (BHASVIC) with kind permission of Mr Chris Thomson. Photo: Barbara Taylor There are many other instances of Brighton murals, many carried out by students in venues such as the Brighton Boys’ Club (late 1930s) and Brighton Girls; Club (1943). The latter involved a series of 8 feet square panels with examples of women’s heroism, such as Grace Darling and Elizabeth Fry. Executed by Naomi Thomson and Elizabeth Fry under the direction of the celebrated poster designer Frederick C Herrick, a member of School staff over several decades. These murals were unveiled by Derek McCulloch, Director of the BBC’s Children’s Hour, before an audience of 400 in March 1943. Other student work in the field included a later scheme in St Francis Hall, Moulsecoomb, by John Pelling, Brian Crouch and Derek Hall. Measuring 22 feet by 9 feet and completed in 1951, it depicted scenes from the life of St Francis of Assisi. This tradition of student involvement in the community has continued to the present day.

During the 1920s there were growing concerns that Brighton was finding it increasingly difficult to attract a sufficient volume of tourist trade both at home and abroad, particularly in the face of competition from towns on the northern coast of France across the English Channel. However, inspiration was drawn from the south of France as one means of drawing attention to Brighton as an exciting place to visit. Nice had been the home of carnivals for centuries and provided the impetus for the Brighton version of the 1920s in which the School of Art tutors and students were highly enthusiastic participants in the design, building and manning of floats. Their work attracted the attention of the national press with preparations photographically reproduced in the Daily Graphic of 15 May, 1922, with finished products shown in photo-article spreads in the Daily Mirror and the Daily Sketch in early July, both of which featured the School of Art’s ‘Art through the Ages’ display. Praise for the School’s contributions in the following year were even more pronounced with an article in the Daily Mirror of 15 June, 1923, entitled ‘Art Students’ Contribution to Success of Today’s Carnival at Brighton’ in which it was also noted that ‘a lion’s share’ of the preparations for the Carnival were undertaken by them. In addition to floats there were 51 banners designed at the School of Art that were presented at the principal events. The organisers thanked both the Head Master William H Evans and the mural painter Lawrence Preston, an important member of the School staff. Sybil Thorndike was one of the Carnival judges.

There were other positive ways in which members of the School of Art contributed ideas about the remodelling of Brighton in order to make it a more attractive tourist destination and place to live. Fine artist Charles Knight played a vital role in conjuring up exciting visual realisations for two schemes in particular, having gained his Art Teachers’ Diploma in 1923 and, in 1924, and holding, for a while, a full-time post at the School.

The first scheme was the proposed redevelopment of Preston Park, a vista that would be visible to all visitors coming into the town on the London Road. The Council commissioned its Superintendent of Parks and Gardens, Captain Bertie MacLaren, to redesign this large open space as it had fallen into a state of decline. His proposals included a grand boulevard that would run from the Steine and encircle the park, the western half of which would feature a 6-acre lake, complete with five large sweeping terraces. Also planned was a rock garden with a waterfall to the lake that would be planted with reeds and populated by swans and water birds. Knight was commissioned by MacLaren to produce a watercolour that would breathe life into his vision, the resulting artwork being submitted to the International Exhibition of Garden Design of 1928.

The second proposed scheme centred on the redevelopment of the Brighton Aquarium. Almost adjacent to the Palace Pier, its Victorian premises had fallen into serious decline in the early years of the 20th century and MacLaren again produced a dramatic design that would provide a fresh vision of a leisure space that would provide a much needed visitor attraction. The design included a glass-roofed concert hall with sliding glass doors that could be opened in the summer, a canopied walk where the orchestra could be heard whilst couples danced on a glazed, electrically under-lit floor. This setting was to be complemented by a rock garden that would occupy the surrounding slopes. Knight’s evocative visualisation of this plan was, like its Preston Park counterpart, shown at the International Exhibition of Garden Design of 1928. However, the proposal was not felt to complement neighbouring buildings, and was thought to be too costly and unsuitable for the site. Nonetheless, in the end, Brighton Corporation still committed itself to the modernisation by David Edwards, the Borough Engineer, of the Aquarium and its two terraces between 1927 and 1929. When re-opened The Times described the upper terrace as having ‘a bandstand from which orchestral concerts will be given and also a fully-licensed open-air café …set with small tables shaded by brightly coloured umbrellas of the type familiar outside the Café de Paris at Monte Carlo and other resorts where the sun shines’.

In fact Brighton in the 1930s was alive with grand plans for modernisation, such as the transformation of Western Road into the ‘Oxford Street’ of the South Coast, the proposed development of Shoreham Airfield as a regional airport, following its purchase by Brighton, Hove and Worthing Councils in 1933, and the commissioning, in 1935. of the County Borough of Brighton Town Planning Central Areas and Development Plan. But nothing perhaps surpassed Sir Herbert Carden’s 1935 plans for the demolition of all seafront buildings on the King’s Road from Hove to Kemp Town (including sweeping Regency crescents and Sussex Square) and replacing them with twenty storey blocks of flats (JMW1) as outlined in his article on ‘The City Beautiful: A Vision of the New Brighton’. However, architects associated with Brighton School of Art worked in many styles: Kenneth Black worked in both the imperialising Mock Tudor vein, as in the King and Queen public house (JMW2) , and in the modern style, as in the new municipal market building, Circus Street. (JMW 3) John Denman, for many years attached to the School, designed many buildings in the modernising compromise between the vernacular and the modern in a 1930s muted neo-Georgian.

In such a municipally progressive context Brighton School of Art became involved with presenting its own fresh, modern and international profile, following the appointment in 1934 of E A Sallis Benney as its Principal and Director of Art Education for the County Borough of Brighton. Sallis Benney had previously been Principal at Hull College of Arts & Crafts, where he had undertaken a substantial programme of reorganisation and doubled student numbers. Having been brought in to Brighton to consider the Board of Education’s 1933 proposals for a three-tiered system of art education that ranged from art classes in schools through to art schools and then to regional colleges of art, Sallis Benney soon put forward his own proposals for an International College of Art, comprising three main Schools - Architecture, Design and Painting & Graphic Art – all of which would have progressive curricula. (BSA2) The Evening Standard of 20 June 1935, reported how Sallis Benney felt that:

The students of the last generation had no such artistic training…hence the intolerance of the antimacassar, aspidistra and the case of stuffed birds. The teaching [at the new International College] will result in a demand for better-designed goods which the producer will not be slow to meet and which will enable us to compete on much better terms with rivals who are sometimes more artistic.

It was also envisaged by Sallis Benney that there would be graduate and postgraduate study in all forms of advanced work, as well as industrial consultancy, at the new College and that it

… would also undertake research work for industry, in the same way that a university did at the present time. The present day artist and designer was not afraid of machinery; in fact, he welcomed it but he realized that it must be controlled by those whose aesthetic tastes had been properly trained.

It was envisaged that the School of Architecture would embrace architectural training alongside related departments of sculpture, painting and decorating, with courses in town planning, civic design, landscape garden planning, interior decoration and architectural model-making. It would also contain a Department with classes in carving, plastering, pottery and tile making. The School of Painting and Graphic Art was planned to include Departments of Drawing & Painting, and Book Production & Commercial Design, the former including mural painting, and the latter dealing with posters, book covers, advertisements, book illustration and decoration, with classes in etching, engraving, mezzotint, aquatint, lithography for art and print, and letterpress printing for compositors and machinists. The third School, devoted to Design, would comprise a Department of Industrial Design and a Department of Women’s Crafts. The former was intended to involve industrial design across a range of practices, alongside facilities for jewellery or enamelling, silversmithing, stained glass and mosaic, window and shop display. Women’s Crafts were seen to embrace embroidery, dress design, fashion drawing, French modelling, costume designing, leatherwork, and textile printing, weaving, dyeing and spinning.

Sallis Benney also anticipated three further independent Departments: Extramural Studies, Teacher Training, and Theatrical and Cinematographic Art. It was the latter that was most radically innovative as students would be able to take classes in cinematography as well as set-design, scene painting, stage lighting, theatrical model making, property designing, and wig-making and make-up. Brighton was an appropriate location for such training as it had bee home to Britain’s pioneering film industry in the closing years of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century.

It was clear that none of these major ambitions would ever be realised without a new building that could accommodate all these new spheres of activity. Accordingly, in 1936, plans were put forward for a new Municipal School of Art, at an envisaged cost of £165, 430. On 24 September of the same year three large architectural schemes were considered by the Town Council: the new Town Hall, the Sea Front Improvement and the new College of Art. The first, John L Denman, designed by John L Denman who had run the Architecture Section at the School of Art during the 1920s and later served as the President of the South-Easter Society of Architects, was rejected, the second put forward for planning and the third, the envisaged College of Art, was approved, having been described in a report prepared by the Education Committee for the Town Council as being central to the region. It would provide ‘the most advanced work in fine art and industrial design and craftsmanship’, pay ‘special attention to the artistic needs of the staple industry or industries of the district’ and, in some cases, offer courses for intending teachers.

However, support for the building of a new Art College was by no means universal at a time of growing political and economic uncertainty. Indeed, the Daily Sketch of 26 February 1937 reported that a Councillor and spectator came to blows during a debate on the matter and had to be separated by a policeman. In September of the following year the scheme was deferred, Councillor Sherrott having described the expenditure as ‘a wasteful and luxurious expenditure’ and the Education Committee as ‘one of the most wasteful Committees you can have’. The Associated Ratepayers Protection League (ARPL) played a dominant role in such debates.With the outbreak of the Second World War, plans for the rebuilding were abandoned but attacks on the School did not rest solely on the proposed expenditure on the new College as antipathy was also directed against the staff, a number of whom were sacked by the Brighton Education Committee in March 1939. A flurry of articles was issued in the national press including the News Chronicle, Evening News and the Daily Sketch, the latter reporting that:

Thirty men and women, many of them well known artists, forming the part-time staff of the Brighton School of Art, have been given notice following allegations that their appointments have influenced by favouritism. Great secrecy has been observed on the matter and last night many of the students were unaware of the decision. The notices expire at the end of the term.

Those sacked included Walter Bayes, Louis Ginnett and Charles Knight. However less than two months later, Brighton Town Council passed a resolution regretting the decision of the Education Committee, requesting that it should rescind the notices given. This it eventually did in a meeting lasting seven hours and twenty-five minutes, its longest meeting on record.

Although Sallis Benney’s plans for an International Brighton College of the Arts failed to materialise in the 1930s, a number of significant practitioners were employed at this time including painters Charles Knight, Louis Ginnett and Morgan Rendle, Morgan Rendle, silversmith Dunstan Pruden, potters Norah Braden and Paul Barron, Ethel Mairet (later a Royal Designer for Industry) and graphic designer Frederick C Herrick. The School of Art also hosted lecture series by well-known authorities such as Anthony Bertram. JMW4 He delivered a series of 12 weekly lectures on the theme of ‘Architecture and Design in Daily Life’ in the Autumn of 1938, having first visited the School in 1937, the year in which he broadcast the well-received series of programmes for the BBC on ‘Design and Daily Life’ In the same period,Hesketh Hubbard delivered several series of public lectures on great artists including, in 1939, one devoted to ‘Ten Great Painters of Europe.’

The School also sought to develop courses in new fields, establishing a Department of Women’s Crafts in 1936. Alice Umpleby was in charge of the department from 1938, having come to fashion design through her professional involvement with printed textiles and fabrics. She believed that a curriculum for shaping the ‘modern fashion expert’ would include the design of fabrics, dress design, fashion drawing, embroidery, the making of accessories, millinery, weaving and the study of the history of costume and theatrical costume. BSA20b She exhibited fabric designs at the 1937 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, also showing two embroidered panels at the Arts & Crafts Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art where Norah Braden and Miss Dean, who taught millinery at the School of Art, were also included.

Other initiatives included window and shop display, a discipline that had featured in the plans for the new building in the form of a display hall in which it was envisaged that there would be bays in which experimentation and research in the field could be conducted and displayed. From 1936 Reginald White, display manager for Rosling’s the drapers in London Road, Brighton, ran classes on window display on two evenings a week. (Display & Co) In the same year he won the national Daily Express Window Dressing Contest. The course also fostered links between the School and local businesses, W C Dudeney, of the Eastern Brighton Traders Association, chairing a series of lectures exploring various dimensions of the subject. Late in 1937, Brighton window display students participated in a competition organised under the auspices of Women’s Wear News andjudged by A Edward Hammond, editor of Women’s Wear News, Sallis Benney and Frank R Metcalf, display manager of Hannington’s Limited.

On the outbreak of War, students from the art section from Westminster Technical School College and the North London Polytechnic School of Architecture were evacuated from London and began classes at Brighton School of Art. At this early stage the School was also provided with various safeguards including the shuttering of its windows, the digging of trenches at the immediate rear of the building, and the provision of Air Raid Precaution (ARP) equipment for dealing with bombs and a first aid post.

The School of Art was able to demonstrate its usefulness to the wider community through involvement with the propaganda campaigns, in which the Women’s Crafts Department provided a particular focus, especially in the ‘Make Do and Mend’ ethos following the introduction of clothes rationing in 1941. During 1942 and 1943 members of the Townswomen’s Guild of Brighton and Hove were keen to follow evening classes on toy, glove and slipper making; by 1944, demand for the Department’s expertise was significant, with class numbers rising to forty rather than the anticipated sixteen. Youth leaders, aged from 14 to 60, received instruction from Mabel Early, assisted by two of her day students, in pottery, embroidery and handbag making. Students were typically involved in activities such as designing a shop display for the Spitfire Fund in 1940 or the production of a 56 feet by 28 feet poster of Winston Churchill for War Weapons Week in 1941. Posters were also designed for the Ministry of Information and the Women’s Voluntary Service. Students also assisted in such tasks as mapmaking for the RAF BSA56 and the production of an illustrated map of Prisoner of War Camps for the Red Cross Society. During the War years the School also provided classes for several thousand members of the armed forces in a range of disciplines.

Following the end of the War Sallis Benney’s longstanding plans to bring regional status to Brighton School of Art were soon realised. In the Spring Term of 1947 Brighton was re-designated as the Brighton College of Arts and Crafts, although the Ministry of Education only gave provisional recognition for this in the light of the perceived difficulties of curriculum development in a cramped building and the fact that any new building plans would be unlikely get a speedy green light in the constrained economic circumstances of the times. Nonetheless, despite such shortcomings, the College was considered by many to be in the top ten of the 200 or so Schools of Art in the country. The Evening News reported in 1947 that:

Brighton has become one of the most important art centres in the country. Students from all over the country, from South Africa and Holland and former underground workers in Norway, attend the already crowded College of Art. So many have chosen Brighton that for the first time there are long waiting lists for some courses, and only those studying for a full-time artistic career can become full-time students.

The fact that there were about 300 full-time and 1200 part-time students with limited accommodation and pressures on access to equipment ensured that plans for a new building were high on the agenda.

It should be remembered that during the War, as thoughts increasingly began to focus on reconstruction as the Allies began to get the upper hand, there were also aspirations to confirm Brighton as the educational hub of Sussex through the gaining of University College or even University status for the municipality. In a 1943 report to the Planning sub-committee of Brighton’s Education Committee it was proposed that the new Art School should be built closer to the Technical College and that ‘if all Brighton’s municipal buildings were grouped around The Level with that open space as a campus, Brighton might have a civic centre of which it could be proud’. Such a bringing together of such constituents presaged ideas about Polytechnics two decades later. It was also proposed in 1943 that a new Town Hall could be erected on the same site, adjacent to the new School of Art, showing how well thought of the latter was from a municipal perspective. Ten years later proposals emerged about the possible relocation of the Brighton College of Arts & Crafts to Falmer, although this was seen as problematic given problems of access for part-time students and part-time staff travelling down from London.

Design was very much to the fore in the public arena in the latter half of the 1940s, the Board of Trade having created the Council of Industrial Design in 1944, an organisation whose first major public display of design in a post-War world was the Britain Can Make It (BCMI) Exhibition held in the V&A in 1946, attended by over 1,432,000 visitors. Many books and magazine articles were centred on themes such as ‘Reconstruction and the Home’ and ‘Homes for the People’, with a variety of department stores, the British Industries Fair and even the Daily Mail Ideal Home exhibitions following design propaganda lines.

The new Brighton College of Art also played its role in such design propagandist activity. In 1947 it mounted its own ‘Design in the Home’ exhibition that included items of furniture, kitchen equipment and electrical appliances as well as a range of pottery, glass, silverware and other domestic artefacts. BSA56 BSA77 The organisation of the display, sponsored by the local Head Teachers’ Association and intended to capture the interest of older elementary and secondary school children, was the task of the Teachers’ Training Department under Ronald Horton, its Head since his appointment in 1944. In the spirit of BCMI, the Brighton ‘Design in the Home’ exhibition included contrasting examples of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ design, an idea that had a long pedigree in design reform circles such as the DIA in Britain or the Deutscher Werkbund in Germany in the 20th century or, chronologically more distant, the ‘Chamber of Horrors’ at Marlborough House (an ancestor of the V&A) in 1852 which sought to warn consumers of ‘False Principles in Decoration’ in the wake of the Great Exhibition of 1851. At the Brighton exhibition of 1947, teacher training staff and postgraduate students introduced the schoolchildren visitors to the exhibits, encouraging them to comment on, and discuss, the exhibits. The correspondent of the Times Educational Supplement of 6 December 1947 felt that the comments passed were lively, intelligent and perceptive. Over 2000 visitors attended the exhibition, held in Circus Street, and smaller satellite exhibitions were circulated around local schools accompanied by an educational pamphlet.

As had been stated by the Victorian educationist Henry Cole in the 1860s, Brighton College of Art did not have specific industrial links in the way that was the case with similar educational organisations in Manchester and Birmingham. Nonetheless, in the 1950s it was well placed to provide expertise in commercial and industrial design and worked with industry through a number of Advisory Committees alongside local, regional and national arts associations. Such activities found their applications in the development of the curriculum. For example, in 1951, the first cohort of students completed the National Retail Association of Furniture Retailers Diploma, launched at the College in 1949 as the first such course outside London. Students on the course were drawn from local businesses, such as George Hilton & Sons of Haywards Heath, Johnson Brothers of Brighton and Rings Ltd of Hove. At the first Awards Ceremony, J Ramage, Director of the Association of Retail Chambers of Trade, noted that it was ‘right that Brighton – one of the loveliest centres of retail distribution in this country – should have taken the initiative’. It was an initiative that was soon followed by Manchester, Nottingham and other centres of art and design education and reflected the preoccupations of national bodies such as the Council of Industrial Design that were also offering educational courses to furniture retailers and buyers. The College established other links with furniture retailing in Brighton as seen for example, in John Bowles’ Duke Street retail outlet where students showed their textile designs.

That there was a high level of technical understanding in student work was confirmed in a speech by Sir Ernest Goodale, a leading textile industrialist who had served on the Council of Industrial Design, a major figure in the formation of the Federation of British Furnishing Textile Manufacturers, and President of the Silk and Rayon Users’ Association, at the Annual College of Art Exhibition at Brighton Museum and Art Gallery in 1953.

In these years the School also worked closely with the Typographical Association to develop a strong printing department and workshops were set up in Circus Street and Sallis Benney asked for the support of Brighton and District Master Printers Association to help in the provision of machinery. This was secured through a government grant of £11,700 and was approved by Brighton Council although, inevitably, it was a matter of some debate before the last machine was installed in 1955. In 1940 there were 57 apprentices attending the School. Ten years later, there were 228, of which 150 were apprentices from local industry. The department was run by E J Gee from 1948 to 1953 when he was succeed by J A P Evans who retired in the 1970s.

Brighton students also continued to be successful in the national context of RSA industrial art bursaries, the gaining of Rome Scholarships, places at the Royal College of Art and the Royal Academy Schools and other prestigious, though less well-known, competitions. These included the Evening Standard Fashion competition which was won in 1955 with a drawing of an Italian-inspired beach outfit by second year student Barbara Hulanicki who later went on to co-found (with her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon) the celebrated Biba fashion and lifestyle company. Featured in the Evening Standard in March 1953 in a drawing style that was swiftly to lead to many commissions in fashion magazines, her design was made up by Norman Hartnell, the Queen’s couturier. Two years later, Susan Rose won first prize in the Daily Telegraph International Wool Secretariat’s National Fashion Competition.

However, the nature of the College of Art’s academic health was far from vocational in any narrow sense of the word, being concerned to embrace a wider social and cultural approach. As was remarked in an article in The Schoolmaster in 1954, the College sought to offer a sound and practical training to those wishing to become professional artists and craftsmen, to give fuller opportunities to apprentices or industrial workers to study the craft underlying their work and train intending teachers. But the college conceives its job in more comprehensive terms than that of merely teaching young people a particular art or craft. The aim is to “educate” them in the widest sense, to provide for their all round development with a view into making them into intelligent and broad minded, as well as technically excellent, workers.

As has been seen earlier, Brighton’s position as a centre for art teacher training had been recognised by the Board of Education since 1914. By the early 1950s it was one of sixteen such specialist centres in Britain and was a constituent college of the London Institute of Education. A key figure in this was Ronald Horton, its head at Brighton from 1944 to 1966, when he retired. Raymond Watkinson, a colleague of Horton’s in the 1960s summed up his qualities thus:

Those who listened to Ronald teaching, who watched him at work in a class, saw him at his easel, talked with him of social or historical matters, soon found what a wealth of knowledge, of wide reference, informed both the teaching and the painting. Beginning thus early, educating himself thus deeply, he amassed a most remarkable library whose special characteristics was its range of illustrated books and prints recording the social life and history of the common people from whom he came: very specially, its children’s books, dating from before the Revolution and coming right into the present, has now augmented the treasures of our National Art Library in the Victoria & Albert Museum; an unrivalled collection of children’s games, puzzles educational toys and toy theatres, has gone to the College of Librarianship of the University of Wales , Aberystwyth. From all of these intimately known, endlessly researched and lovingly ordered resources, students of the ATC course here, year by year from 1946 [sic] to 1966, were sumptuously fed.

In addition to the Art Teacher’s’ Certificate, the Art Teacher Training Department offered a wide range of other opportunities, including refresher courses for teachers from Brighton and the surrounding region. There was also considerable direct contact with schools in the area as for many decades Brighton College of Art had been responsible for the control and development of art education in municipal primary and secondary schools. Ties had been further consolidated through the awarding of municipal scholarships for children to attend the College of Art or, before that, the School of Art. In the post War period Ronald Horton took on the role of the Schools’ Art Superintendent. The broad-based educational rationale at Brighton, to which The Schoolmaster had referred in 1954, took on a particularly liberal edge in the Art Teacher Training Department. Students participated in a wide range of activities including oral history, theatre productions, music and written studies, all of which were acknowledged as part of the curriculum. In fact, the ATC students were much more geographically diverse than the student population of other departments in the College. They came from all over the world, their countries including Africa, Ceylon, China, Cyprus, India, Pakistan, and the West Indies, and significantly enriched the collective and individual experiences of the student body as a whole.

The period between Sallis Benney’s retirement as Principal of the College of Art in 1958 and the formation of Brighton Polytechnic in 1970 proved to be a testing time for art and design education at Brighton on a number of fronts. These may be summarised by three distinct themes: firstly, the managing and implementation of a large-scale building programme at Grand Parade; secondly, the fierce debates about the nature and content of art and design education set off by the Coldstream and Summerson Committees’ advocacy of a new Diploma of Art and Design (DipAD) to replace the National Diploma in Design (NDD); and thirdly, the art and design community’s perceived difficulties in adjusting to such changes alongside those of becoming a constituent part of a new type of higher education institution – the Polytechnic. Although certain aspects of all of these concerns are dealt with elsewhere (Chapters 4,5, 6 and 7), it seems appropriate to outline here some consideration of the difficulties facing the new Principal, Raymond Cowern, and his staff and students in the years between his appointment in 1958 and his retirement in 1974.

Arguments for a new building had gathered pace in the 1930s with Sallis Benney’s ambitions for establishing an International College of Arts & Crafts in Brighton although, with the very pressing realities of cramped conditions and growing student numbers, they became increasingly compelling in the 1950s. In 1958 the decision was taken to erect the new building on the Grand Parade site although, due to the many deliberations about its ‘fit’ with the environment, the commencement of rebuilding was delayed until 1961-62.

The original rebuilding plan embraced the whole site bordered by Grand Parade, Edward Street, William Street and Carlton Hill, considerably larger than the ground space occupied by the building that eventually went up. The larger complex would have included residential student accommodation and car parking. The Town Council decided to employ the municipal architect, Percy Billington, for the task, rejecting the Education Committee’s earlier enquiries into the possibility of bringing in outside architects sympathetic to the Regency style. Considerable local anger had been expressed about the possibility of demolishing a Grade II-listed terrace of Regency houses and ignoring the advice of the Royal Fine Art Commission. The Ministry of Education, the Royal Institute of British Architects and Royal Fine Art Commission all expressed views, resulting in the appointment of Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall and Partners to cooperate with Brighton Corporation’s planners and architects to produce a design solution that was aesthetically and environmentally acceptable. Michael Viney described it:

Decisively modern and pseudo anything, the building nonetheless makes gradual easy transition from the Regency bow-fronts adjacent in Grand Parade to the sharper, cleaner, more functional lines of 1958.

Even so, it was decided to take further advice and Sir Hugh Casson was brought in as an advisor with resultant changes in the façade and roof line and the production of a modern building appropriate for the needs of art and design education in a changing contemporary world.

As is discussed in Chapter 4, Phase 1 of the Project, the Wing along William Street, was completed in late 1969 and housed all of the vocational about here and craft courses. Phase II, which was the most complex as it involved the demolition of the century old Brighton School of Art and the decommissioned Roman Catholic Apostolic church which had housed art teacher training and hairdressing, was completed in 1967. Housing Fine Art, the Library, the Refectory and the Hall, it was formally opened by the President of the Royal Academy, Sir Thomas Monnington in June. Phase III, housing the Gallery, Graphic Design Studios, Printmaking, Photography, and offices for the Directorate and the Administration, was completed in 1969. However, as indicated above, the site that these three phases occupied was considerably smaller than that first envisaged. As a result, not all buildings could be housed in new premises: Fashion and Textiles were in a former school in Finsbury Road, Architecture and Design in Circus Street and St. John’s, Three Dimensional Design in Circus Street, Complementary Studies in Glenside, Art Education Studies in Sussex Square, and the Art Centre in Bear Road, and there were no student halls of residence.

Substantive changes in the nature of art and design education were unfolded during the 1960s and early 1970s, most significantly due to the consequences of the findings of the National Advisory Council on Art Education established under Sir William Coldstream in 1959 and the National Council for Art and Design set up under Sir John Summerson to administer the new schemes for the new Diplomas in Art and Design (DipAD) in 1961. Under this new framework students would take a one-year pre-Diploma course (subsequently widely known as Foundation Courses) followed by a three-year specialist course in one of four areas: Fine Art, Three Dimensional Design, Graphic Design and Fashion/Textiles. These new diplomas were conceived as degree equivalent courses with 15% of the curriculum devoted to Art History and Complementary Studies as a means of enhancing the vocational with an intellectual enhancement. The tension that this caused in many Colleges led to the student unrest of 1968, the Brighton dimensions of which are discussed in detail in Chapters 6 and 7. A number of Brighton students were quite politicised, with Ronald Horton, John R Biggs and Ray Watkinson supporters of the Communist Party. Indeed, the latter, a staunch Communist Party member throughout his adult life, used to take students to the Communist Art School in London in the 1960s and was a participant in the Brighton and Hornsey occupations of 1968.