An Active Form of Surrender: Teaching in Design Higher Education

James Corazzo, University of Derby

The Art Design Media Subject Centre made six awards under the Art Design Media Teaching Fellowship Scheme for the academic year 2010/11. James Corazzo, one of the ADM Teaching Fellows from 2010-11 reports on his experience. ... After ten years of teaching graphic design I began to wonder if the biggest obstacle to my students’ learning might actually be me...Two key points of reference framed ...

ADM-HEA Teaching Fellowship Projects 2010-11

The Art Design Media Subject Centre made six awards under the Art Design Media Teaching Fellowship Scheme (ADMTFS) for the academic year 2010/11. The scheme was part of ADM-HEA’s aim to support the professional development and recognition of staff in HE and to ensure that their teaching is valued and rewarded. For more information about the scheme

James Corazzo, one of the ADM Teaching Fellows from 2010-11 reports on his experience here. We shall be publishing further reports in Networks issue 18.

An Active Form of Surrender: Teaching in Design Higher Education

What were the aims of your project?

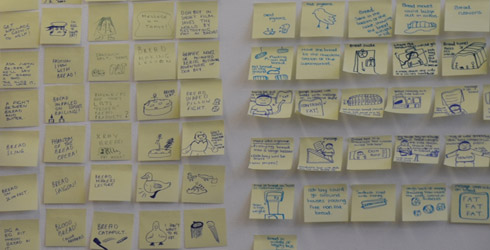

If you were going to chose an image that summed up your teaching practice what would it be? This is the one I chose:

Figure 1: My teaching practice

Some might argue that this image represents some level of success, perhaps it does, but it’s also a long way from ideal because so much depends on the dog and, as an educator, it troubled me that I wasn’t enabling the mice to ride their own bikes.

After ten years of teaching graphic design I began to wonder if the biggest obstacle to my students’ learning might actually be me. The ADM-HEA Teaching Fellowship presented an opportunity to examine this notion.

Two key points of reference framed my approach. The first was a design course at NHL University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. I visited in 2009 and it was quite unlike any other design degree I have seen. Committed to constructivist educational principles – many that question accepted pedagogies – its core ethos: ‘What you need to know and need to do is not the teachers’ decision. On the contrary, the idea is for you to discover for yourself what you need to know and how you need to do things’ (Communication & Multimedia Design Competency Profile, 2009).

Figure 2: Communication & Multimedia Design ethos

The second was quite literally a road junction a few miles from NHL University that had been designed by Hans Monderman, a traffic engineer obsessed with improving road safety. Monderman's vision for safer roads was counterintuitive: if you make driving seem more dangerous you could improve road safety. He believed that road signs cultivated a culture of dependency and were a manifestation of how badly the road had been designed: ‘the trouble with traffic engineers is that when there's a problem with a road, they always try to add something… to my mind, it's much better to remove things.’ Monderman’s shared space concept has now been exported all over the world. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b018xs8t

Figure 3: Inspired by Hans Monderman, Makkinga was the first settlement to remove all road signs, markings and signals. Drivers appear to successfully read the village context and adapt accordingly.

These reference points are both important to me because they flip our shared notions about how things should be done, and in the process ask challenging questions about accepted practices. I began to ask myself: what could I take away from my teaching? What effect would a well-designed ‘surrender’ have on the students learning?

What did you do?

I proposed to spend one semester surrendering as many established (graphic design) pedagogies as I could, including the curriculum, the delivery and content of lectures, and the control of the deadlines. In January 2011 we began the semester-long 48-credit module with a cohort of eighteen second- year graphic design degree students.

Figure 4: scheme of work

Surrender the curriculum

I made the outside world the organising principle of the entire curriculum. This meant that everything became a live project; real clients, real problems, real deadlines. We also worked with the Lost in the Forest Institute (http://litfi.ac) to realise a social design project.

Surrender the content

I replaced the front-loaded lecture programme with an on-demand model that would respond very deliberately to the needs of the students in relation to the particular project they were working on.

Surrender long deadlines determined by the module

I dramatically restricted project durations and now they lasted from a couple of days to a week at most. Furthermore, I made very little attempt to mediate the live projects for the students. Instead, we were interested in exposing them to the messy complexity of dealing with people.

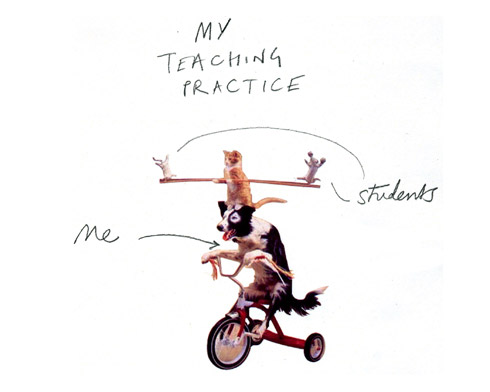

Figures 5, 6, 7: Real bread campaign for howies to combat obesity in young children

What have been the key outcomes of your project?

There were a number of significant outcomes but I’m going to focus on two: purposefulness and project length in relation to deep learning.

Make it Purposeful

The projects were all live and we didn’t mediate much between client and student. They ranged from work for photographers, iphone apps for a festival, an identity for an eco-home builder, to designing interventions around obesity in young children. Interesting and varied perhaps, but for the students it was the live-ness that resonated, rather than the project content.

It’s going towards something rather than to get a mark, or something to put in your portfolio, it may actually become something [Helen].

You want to take it on more because you’re going to see an actual outcome... it will be out there [Tom].

We, as staff, need to believe that the tasks we tackle are important and meaningful so why shouldn’t our students feel the same about the ones they do? For me it raised the question about differentiating between what I think is going to be meaningful and the things students actually find meaningful. Design thinker Bruce Mau argues that educators should:

...use action and real purpose to accelerate education and development. So rather than cutting education off the challenges we face we use the challenge as a kind of accelerator, rocket fuel to entrepreneurial education (Mau, 2010).

Deep learning through short projects

Generally speaking design education tends to link project duration with depth. And of course some projects have a complexity that requires long periods of time to research and develop. But too often long projects result in an ennui for the student that can impact on motivation and attainment. For graphic design students short projects place an emphasis on action and can give urgency to thinking, and I began to see more work being produced in a one-week project than if it had been four weeks.

I actually enjoyed the smaller time frame; it helped me to produce ideas more quickly [Laura].

Short projects in a larger module, although discrete in themselves, develop the opportunity for an iterative investigation of a student’s own design process.

I have a tendency to leave things to the last minute but with these live projects it’s extremely difficult to do so and come out with a positive experience. It became clear that organisation is the key and exactly the point where I start going wrong [Dave].

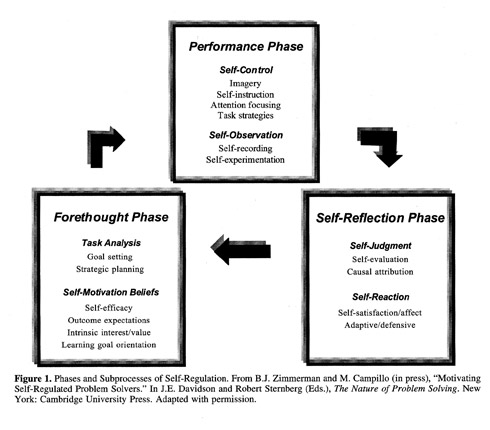

They create a kind of repetitive curriculum, in turn creating the opportunity for small-scale failures and quick feedback/forward loops. Looking at the students’ reflective accounts, they suggest that a deeper learning emerged because the students were able to make a series of connections across projects in relation to their own performance. Most profoundly they began to examine their own thinking and learning. This meta-cognitive approach is evident in theories of self-regulated learning.

Self-regulated learning is an active constructive process where by learners set goals for their learning and monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behaviour, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features of the environment (Pintrich and Zusho, 2002, p.64).

Self-regulated learning is a cyclical process with distinct phases, and what emerged from this project was the inter-relationship between purposefulness, short projects, the opportunity to make tiny failures, and quick feedback. This provided an opportunity for the students to recalibrate, reflect and go again the following week.

Figure 8: Phases and Subprocesses of Self-Regulation diagram

How have students benefited, or how will students benefit from your project?

There was a noticeable upturn in marks with over half the cohort attaining a whole class-mark above their average degree mark. The real benefits were in the less tangible and more difficult to measure areas of self-efficacy, self-confidence, and the development of a meta-cognitive approach to learning.

How can the wider art / design / media subject community benefit from your project?

It should be noted that this was an action research project, run on a small scale and much of the evidence is observational. As such I offer the following observations for the broader art and design community:

- Motivating and challenging students to achieve their full potential is at the core of an educator’s teaching practice. This project raises questions about the significance of what we ask students to do.

- Short projects are not mutually exclusive to deep learning. They can offer a way to introduce the opportunity to fail within a module without real jeopardy, with good and immediate feedback they are particularly useful for developing a meta-cognitive approach because they create the opportunities for students to adapt strategies and try these out.

- Self-regulated learning model has the potential to be highly suited to design education.

- Getting out of the way can be difficult and finding the sweet spot can be even more challenging. I would be very interested to hear from people on what we might call ‘non-teaching’ or ‘the space between teaching’ or ‘actively not teaching’; strategies where it might appear we are surrendering control but which have been designed to encourage learning.

About and thanks

This project was undertaken when I was Pathway Leader for BA (Hons) Graphic Design at Stockport College. I would like to thank all of the students that so enthusiastically entered into this project, Lost in the Forest Institute for the collaboration, the ADM-HEA Fellowship Scheme for funding it, and Brian Eno for the title. I’m now working at University of Derby and we’ve just held a Higher Education Academy workshop ‘Redesigning (Graphic) Design Education’ where students, tutors and practitioners spent a day generating a series of proposals and models for design education.

If you would like to join this conversation or would be interested in taking part in a future event please contact j.corazzo@derby.ac.uk or http://www.rgde.co.uk

References

NHL University of Applied Sciences (2009) Communication & Multimedia Design, Competency Profile. http://www.cmd-leeuwarden.nl/International

http://www.cmd-leeuwarden.nl/?node=743

Mau, B. (2010) What is the Centre for Massive Change? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XpRxAovJM7g. Date accessed 28/02/12.

Pintrich, P. R. and Zusho, A. (2002) ‘Student motivation and self-regulated learning in the college classroom’ in: J. C. Smart and W.G. Tierney (Eds.) Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, Volume XVII, New York, Agathon Press.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002) ‘Becoming a Self Regulated Learner: An Overview’, Theory into Practice, Vol. 41 (2).

Images supplied by James Corazzo

Figure 3: Photo: Andrew Burmann

Figures 5, 6 and 7: Photos: Lost in the Forest Institute

Listing image: section taken from Figure 1

Header image: section taken from Figure 6