The Art of Surviving and Thriving: How Well are Access Students Prepared for their Degrees in Art and Design?

Samantha Broadhead and Sue Garland, Leeds College of Art

This Learning and Skills Improvement Service (LSIS) in partnership with the Institute for Learning (IfL)-funded project aimed to evaluate how well ex-Access students achieved on undergraduate Art and Design degree programmes when they progressed internally within a specialist art college. These students came from diverse backgrounds and often had ‘unconventional’ educational histories. The pr...

Keywords: transition, curriculum, mature student, art, design

Abstract

This Learning and Skills Improvement Service (LSIS) in partnership with the Institute for Learning (IfL)-funded project aimed to evaluate how well ex-Access students achieved on undergraduate Art and Design degree programmes when they progressed internally within a specialist art college. These students came from diverse backgrounds and often had ‘unconventional’ educational histories.

The project considered the themes of familiarity, critical rigour and group profile, in relation to the progress and development of ex-Access students on their degree courses. The importance of FE and HE colleagues working together to improve the student experience during the transition from FE to HE was highlighted by this project.

Introduction

The Futurists, a group of Italian artists, proclaimed in their manifesto ‘When we are forty let younger and stronger men than we throw us in the waste paper basket like useless manuscripts!’ (Marinetti, 1909)

This extreme statement demonstrates an attitude that only the young and the male have anything important to contribute to art and design culture. However, the mature students from Access courses in FE colleges have aspirations that mean they deserve to be taken as seriously as artists, designers, photographers, filmmakers and craftspeople.

The aim of this research project was to discover how well Access students were prepared for HE level study in art and design at a specialist art college. This project was supported by the Learning and Skills Improvement Service (LSIS) in partnership with the Institute for Learning (IfL). LSIS is the sector-owned body to develop excellent and sustainable FE provision. The IfL is the professional body for teachers and trainers in the sector.

The reasons for this investigation were firstly to find out how the Access course helped the students and what needed improvement. This had conventionally been done using the quality processes that are part of self-assessment reporting. However, this approach had been very focused on the students’ experience before they left FE. Progression figures from such evaluations used to inform quality judgments but these did not tell the course team how well the Access Course met its core purpose (giving the students the knowledge, skills and strategies necessary for surviving and flourishing on their degree courses).

A second reason for this study was to make sure that the Access course continuously improved to give students the best chance of gaining future places at HE in an environment which was becoming increasingly competitive.

Thirdly, the project aimed to start a dialogue with HE course leaders. Responsibility for the transition from FE to HE could not be laid solely on the shoulders of Access tutors. The findings of the project were shared with HE staff where issues of curriculum design and pedagogy could be worked on together in the spirit of Joint Practice Development (JPD) (Fielding, 2005).

In order to understand the issues that surrounded the transition from FE to HE 18 ex-Access students on various art and design degrees and in different year groups were asked to share their experiences with the researchers. The ages of the students in the sample ranged from early twenties to late fifties. There was a gender bias as only two men took part. This reflected the student population of the Access course in general which tended to attract more women than men.

Methodology

This study has been strongly informed by two key ideas, firstly the idea of capturing student voices, through a range of methods including focus groups, interviews and reflective writing (Ward and Edwards, 2002; Coffield, 2009; Hudson, 2009). This study wanted to capture the voices of Access students in particular for social justice and democratic reasons (Kidd and Czerniawski, 2011, p.xxxvi). The study would give the Access students an opportunity to express their opinions that potentially could change the college’s policies and practices. Voices - a term expressed as a plural was used in anticipation that the participants would have diverse and sometimes contradictory attitudes towards their experience of HE (Thomson in Kidd and Czerniawski, 2011, p.22). The second was the idea of trustworthiness in educational research, a concept developed by Bassey in relation to case study research (1999, p.118).

The ex-Access students from the previous five years who were still at the art college were emailed using their college email account; they were told about the project and invited to take part. Those who agreed took part in focus groups and one-to-one interviews. Any reccurring themes that came from these activities were confirmed by a final focus group discussion. The participants were then given a written account of the findings and asked to comment on them. The questions used to drive the discussions and interviews were semi-structured.

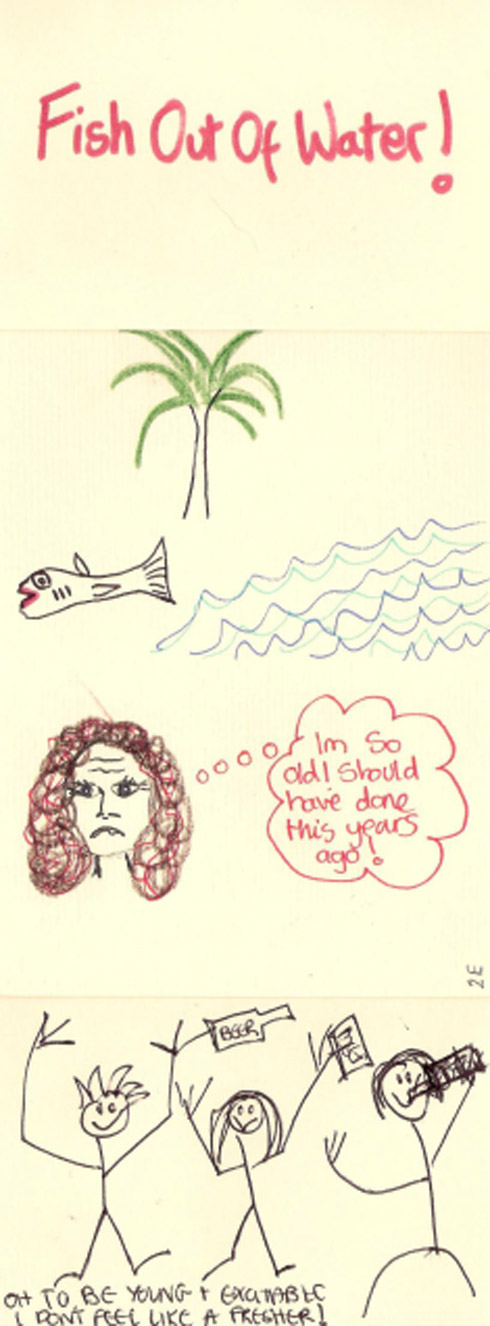

In addition to the interviews eight ex-Access students who were in the first term of their degree during the project were each given five postcards pre-addressed to the Access to HE course leaders. Each of these students was asked to jot down any comments or drawings about their experiences during their first term and informed that these could be sent through internal post. Of the eight students, three sent a total of eight cards back. These written and drawn comments were analysed alongside the other types of data collected in the project.

Pseudonyms were used in the interview notes and in the focus group minutes/post-it notes to protect student identities.

Analysis of results

Generally students reported that they felt really happy with their Access course, as this quotation from the interviews shows:

I felt well prepared even though completely out of comfort zone. The tasks done on Access did prepare me well for example mark-making at start of course. The sound project on Access was good preparation it gets you thinking (Jenny, November 2010).

There were some issues which kept emerging in the interviews and the focus groups. The points that were referred to by at least three different participants were organised into themes (familiarity with context, critical rigor and group profile).

Theme 1: Familiarity with Context

One common theme that came up in many of the interviews, focus groups and postcards was the idea of familiarity. Students reported that they were happy that they had already worked with art and design briefs, practiced putting a presentation together and had worked in the various workshops using a variety of techniques and materials. In response to the question ‘What ways did Access prepare you well for your degree course?’ Students repeatedly reported how happy they were that they had had experience in responding to briefs and they recognised the brief format. Art and Design education conventionally uses the brief to drive its delivery. It aims to promote experiential learning and problem-solving and self-directed research (Walker, 2005, p.38). The brief states aims and objectives and sets constraints which the student has to work within. From the next two responses it seemed that the actual layout of the brief helped understanding and promoted confidence:

Briefs, both in terms of content and format, although they are written in a complicated way on the degree, I understand how to deconstruct them (Carrie, November 2010).

Briefs, the same format helps. Familiarity college life helps (November 2010).

As the brief was the tool that drove what the student did on their course, and it was their response to the brief that would be graded, it was not surprising that they would see this as an area of importance. Perhaps the researchers had taken this for granted; it could be that other students coming from other feeder institutions did not use briefs in the same way to study art and design topics. This also linked to the idea of scaffolding where the brief provided a structure, which could be practiced with support at Access level, then on the HE Course the scaffold of the brief remained, but students were able to work more independently and with more complexity.

Also, having the confidence to go into and use workshops was something that was seen as very helpful to the ex-Access students. Again, perhaps the researchers had taken this for granted. However, many students would come from institutions which do not have specialist workshops and to go into this situation for the first time could be intimidating. In order to use workshops effectively students needed to manage their time effectively, be health and safety aware and also have good working relationships with workshop technicians and other workshop users.

Having been in workshops and college and done workshop techniques was good preparation I was able to build on skills from Access (Carrie, November 2010).

Workshops were helpful, to go in and be shown how to use machinery. Having skills in some workshop areas gives you confidence when entering new ones (Eileen, November 2010).

The idea of scaffolding was inherent in the students’ experience; they were able to build on their past experience to do more experimental and challenging work in the future. When the idea of familiarity was revisited with the final focus group (December, 2010) an interesting point was made. This was that there was a feeling of excitement and anticipation when doing something new. If things were too familiar then the thrill of doing something new could be lessened, and students who progressed internally may have felt they actually missed out on something.

Elements that were familiar were comforting but also reinforced to the student that they had chosen the right course in the right institution for them. Access students might have given up a lot, financial security or a previous career to do their HE course, so something as simple as familiarity might be important to mature students. This had the potential to cause a tension with the HE staff values that encouraged a break with past learning as described by Hudson (2009, pp.95-96) and Robins (in Addison and Burgess, 2003, p.45). Within the period of transition it may have been good to have signifiers from the past for reassurance.

Theme 2: Critical rigour

A second theme that was identified by the ex-Access students was that of critical rigour. There was a difference in the critical feedback students got at degree level from that on their Access course. This was an important area to get right, Access tutors aimed to build confidence and encourage students through positive feedback. However this could mean that students were not prepared for the intensity and depth of critical analysis involved in their degree course. Also, the feedback could be quite negative and students needed to be able to deal with this without losing motivation and self-belief. This next quotation makes the point that the transition between FE and HE marks a difference in how tough students need to be at this turning point: ‘…FE staff teaching HE programmes report a profound sense of responsibility as they prepare (‘toughen up’) students throughout the transition from [FE to HE] (Beaton, 2006, p.12).

Part of art and design pedagogical practice was and is based on the crit where work is displayed and discussed, often in a group in the studio. Students would receive formative feedback from peers or members of staff. The visible and public nature of this format was different from feedback that might be received in a tutorial or written at the end of an assignment which was a more private format. The researchers had memories of the anxiety and tension of their own first crit at art school. A discussion about the strengths and weaknesses was found in the Staff Guide published from an ADM-HEA project called Critiquing the Crit (Orr, Blythman, Blair, 2008, p.7). At degree level this could seem quite negatively critical to a student who was used to a more supportive learning environment. This was echoed on a post-it note comment from the first focus group which indicated that the crit seemed to have been a bit of a culture shock:

I wasn’t prepared for such critical but still constructive criticism of my work (October 2010).

When John responded to the question ‘How did Access not prepare you for Higher Education?’ he was very critical of the way crits were conducted on Access.

Access should show people that you couldn’t wander away from a crit. This is about mutual respect. Crits can be too demoralizing. Parameters for crits should be set e.g. no wandering off (John, November, 2010).

From John’s comments it seemed that the crit was a more informal process on Access whereas on a degree they were more disciplined and controlled. How to give and receive critical feedback was a skill that needed to be developed as much as the practical and academic ones associated with workshops and presentations. Phrases like ‘more lenient’ and ‘more laid back’ were used to describe Access; this approach had benefits and dangers as this student reported:

Access tutors were more lenient which generally works well for mature students, but they could have difficulties adjusting in the future, although this wasn’t an issue for me (Marie, November 2010).

This was an example of how staff values could be very different (Casey et al, 2006, p.28). Access staff valued supportiveness whereas HE staff valued setting challenging goals and getting students to be independent. As the two sectors were on two different campuses the opportunities for dialogue were few. It could be argued that a dialogue between FE and HE staff could contribute both to developing pedagogies and an increased understanding of critical rigour. Access tutors needed to be informed about the expectations HE staff have.

Theme 3: Group Profile and Student Identity

The following were typical of student reponses to the question ‘How well, and in what way, did Access prepare you for your degree course?’

To mix with other students all with very different backgrounds, not necessarily in art.

Varied ages – knowledge/ Experience.

Showed you how to integrate with the other students in collaboration projects (October 2010).

The varied group profile of the Access to HE course seemed to be valued by ex-Access students and this theme came up again and again throughout the interviews and the final focus group. The researchers did not expect this to be such an important issue, as it was assumed that HE courses would have some level of diversity in the student body. Within the context of this project it seemed that the student body of HE is actually less diverse than expected. This could be understood in terms of class, gender, ethnicity, and race. However, the aspect which the ex-Access students picked up on was age. This was visually communicated through drawings that one student made on the postcards that were given to ex-students on which to express their feelings when starting their new course (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Postcards from Ex-Access students sent in the first term of their degree

Figure 1: Postcards from Ex-Access students sent in the first term of their degree

During the one-to-one interviews students commented on how they were not prepared for being in a minority and feeling the differences between themselves and other students in terms of age. This difference affected cultural and social interaction and increased the time students took to feel they belonged to their new course. This was felt not just by students in their forties and fifties but also by students in their mid-twenties and early-thirties. This was demonstrated by one student when, in response to the question ‘In what ways does being a degree student differ from being an Access student?’, said:

How you are spoken to is a big difference, like when the tutor is talking to 18/19 year olds. Being part of a group of young students being shouted at to be quiet which feels alien when you are 30. It was good to have Emily and Nicola around, so we could work in a kind of in a bubble and forget that most students were 10 years younger (Jade, November, 2010).

Another student, Adrian, who had been in his late twenties and actually the youngest on his Access course, said he felt really strange being the oldest in the group, this affected how he settled into the new course. He said that all they (the younger students) wanted to do was to play games and he had already been through that phase and he was not interested in that any more. This student felt alienated from his younger peers (Adrian, November 2010). But what Jade pointed out was the importance of having other mature students on the course. The support they received from each other, a feeling of belonging to a small community of mature students, helped them through this transitional time. This was confirmed by comments made by another two students who took part in the final focus group. There were three mature students on their course and they were glad that they could all be in college together during the first term.

There were positive aspects to being an older student as Carrie says:

The mix of people is very different. Some aspects of the degree seem geared to younger students, although hasn’t impacted on my work. I enjoy being in the ‘mentor’ position for younger students. I like to help students who are struggling. I feel Access prepared me well (Carrie, November 2010).

Older students can enjoy helping younger students; this can improve the self-esteem of both parties. The inclusion of students with more life experience could be a positive influence on group dynamics. However, during the final focus group one student felt that group discussions were more difficult on degree because younger students were reluctant to debate issues or challenge the ideas put forward by the tutors. Discussions on the Access to HE course were seen as a strength, which mature students enjoyed. This passive role that younger students adopted was also remarked upon in one of the interviews, when students were asked ‘In what ways did Access not prepare you well for your degree course?’

I was not prepared for lack of open-mindedness amongst fellow students. There seems less academic/intellectual vigour – students are sticking more to what they are told to do (Marie, November 2010).

It seemed that the Access students enjoy the social aspects of learning art and design practice. They engaged with the community of the studio and welcomed opportunities for debate and discussion; this is how they developed skills in critical thinking. They also enjoyed thinking for themselves and taking ownership of their own creative space. Access backgrounds may actually be advantageous in the sense that they have had a different educational background from that of A-level students. The issue may not be directly concerned with differences in age but in differences in previous teaching approaches. The traditional A-level student, who had not studied on a diagnostic art and design course might not be as confident in expressing opinions, questioning ideas suggested by tutors and managing a studio workspace (Swift and Steers, 1999 in Hardy, 2006). The students had different expectations of the teaching and learning process; this could be what caused feelings of frustration. A mature student who always answered the tutors’ questions where others were silent could have felt even more different from the rest of the group, in that they were visibly behaving in a different way. Yet there may have been few other opportunities for the dialogue that these students enjoyed.

Conclusion

The project discovered that in spite of high withdrawal numbers, Access students who persisted felt that they had been well prepared by their FE course to succeed at HE. There were three main themes that students felt were important. The first theme was that the familiarity of formats and procedures like the brief, the presentation and the use of workshops were very much appreciated.

The second theme was that of critical rigour, where students were not always prepared for the degree and intensity of criticism they would receive from staff. There was an implication that some crits in Access to HE were too laid back or lenient and perhaps should have been more formal.

The third theme that concerned ex-Access students was that of the lack of diversity of group profile. The Access students felt themselves to be in a minority within a group of much younger students who had come to college through a more traditional route (National Diploma or A-levels and Pre-BA Foundation course). This was connected to the frustration ex-Access students felt when in college where the younger students were reluctant to take part in studio debates.

A couple of the students, Marie and Adrian, reported feeling quite isolated because their social interests were not the same as the rest of their group (fashion, gaming and drinking). On courses where there were three or more ex-Access students the transitional stage seemed to have been more positive. Ex-Access students seemed to stick together and support one another within the college environment.

The Learning and Skills Improvement Service (LSIS) in partnership with the Institute for Learning (IfL) funded this project for six months from September 2010 to March 2011.

Biographies

Samantha Broadhead graduated from Lancaster University in 1989 with a Visual Arts degree, later that same year she worked as a community artist in the Kirklees Area. Subsequently she completed an MA in Art History at Leeds Metropolitan University.

She has worked as a practising artist and tutor within formal and informal art and design contexts. Her interest has been in working with mature students in gallery spaces, penal institutions, Further Education Colleges and Higher Education Institutions. She is interested in art and design educational research because it aims to contribute towards improving the student experience. Samantha is currently working as an Access Course Leader and a critical studies tutor in a specialist art college.

Sue Garland graduated from Newcastle University in 1975 with a Fine Art degree, completing a PGCE in Art Education the following year. She worked as a practising designer/maker and tutor in a range of contexts. Her main focus has been working with adults in a wide variety of community and college settings. For the last ten years she has run an Access course in a specialist art college, and now teaches part-time on that course.

Contact information

sam.broadhead@leeds-art.ac.ukReferences

Addison, N. and Burgess, L. (2003) Issues in Art and Design Teaching, Oxon, Routledge.

Alexander, R. (2006) Education as dialogue: moral and pedagogical choices for a runaway world, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Institute of Education in conjunction with Dialogos UK.

Bassey, M. (1999) Case Study Research in Educational Settings, Buckingham UK, Open University Press.

Beaton, F. (2006) ‘HE in FE: whose Professional Teaching Standards?’ Educational Developments: The Magazine of the Staff and Educational Development Association (SEDA), Issue 7.1, March 2006, pp.12-13.

Casey, H. et al (2006) “You wouldn't expect a maths teacher to teach plastering…”: Embedding literacy, language and numeracy in post-16 vocational programmes – the impact on learning and achievement, National Research and Development Centre for Adult Literacy and Numeracy found at http://www.nrdc.org.uk/publications_details.asp?ID=73. Date accessed: 02/10.

Coffield, F. (2009) All you ever wanted to know about learning and teaching but were too cool to ask, London, Learning and Skills Network.

Coffield, F. (2006) Just suppose teaching and learning became the first priority, London, Learning and Skills Network.

Dadds, M. and Hart, S. (eds) (2001) Doing Practitioner Research Differently, Abingdon, Oxon, Routledge.

Fielding, M. et al (2005) Factors Influencing the Transfer of Good Practice, Nottingham, DfES Publications.

Hatton, K. (2008) Design Pedagogy Research, Huddersfield, Jeremy Mills Publishing.

Hodkinson, P. Sparks, A. Hodkinson, H. (1996) Triumphs and Tears, London, David Futon Publishers.

Hudson, C. (2009) Art from the Heart: the perceptions of students from widening participation backgrounds of progression to and through HE Art and Design, National Arts Learning Network.

Kidd, W. and Czerniawski, G. (2011) The Student Voice Handbook: Bridging the Academic/Practitioner Divide, Emerald Group Publishing.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E (2009) Situated Learning; Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Leeds College of Art (2010) Further Education: Student Achievements and Career Routes, 2009-2010, Leeds College of Art, http://www.leeds-art.ac.uk.

Marinetti, F. (1909) ‘The Futurist Manifesto’, http://cscs.umich.edu/~crshalizi/T4PM/futurist-manifesto.html. Date accessed: 02/10.

Orr, S. Blythman, M. Blair, B. (2008) Critiquing the Crit: Staff Guide, http://www.adm.heacademy.ac.uk/projects/adm-hea-projects/learning-and-teaching-projects/critiquing-the-crit. Date accessed 02/10.

Walker, A. (2005) ‘Teaching Landscape Through Story-Telling: Learning from the subjective to transverse disciplines’, CEBE Transactions, Vol. 2, Issue 3, December 2005, pp.30-41.

Ward, J. and Edwards, J. (2002) Learning journeys: learners’ voices, London, LSDA.

Header and listing image: section from Figure 1: Postcards from Ex-Access students sent in the first term of their degree