Challenges to learning and teaching relations in higher education studio environments

Alison Shreeve and Ray Batchelor, Bucks New University

This project set out to explore what made for positive relations for learning in the art and design studio environment where the primary mode of teaching is through a dialogic approach which engages students with ongoing project work. The importance of one to one teaching is still maintained by most faculty, in spite of economic pressures to adapt to large groups with less contact time. This st...

Keywords: relations, engagement, studio learning, one to one, tutors, students

Abstract

This project set out to explore what made for positive relations for learning in the art and design studio environment where the primary mode of teaching is through a dialogic approach which engages students with ongoing project work. The importance of one to one teaching is still maintained by most faculties, in spite of economic pressures to adapt to large groups with less contact time. This study also identified that positive learning opportunities resided in peer learning and group based activities, but these may also entail relations between tutors and students. Through semi-structured interviews with students (N=7) and tutors (N=7) the researchers looked for positive ways in which students were supported to learn and for those situations which were less successful or presented obstacles to learning. The main outcomes indicate that relations are influenced by roles structured by the university, the professional practice and by personal trajectories or dispositions of students and tutors. Ambiguity is likely to exist in the fluid relationships required to negotiate learning in a higher education environment.

Aims and Objectives and Rationale

Art and design takes for granted much of the pedagogic practice which is the norm or the signature pedagogy (Shulman, 2005, Sims and Shreeve, 2012) of the discipline. Researchers external to the discipline have noted that there is a distinctive partnership in the learning process:

Alongside this informality is a greater sense of community and partnership between staff and students in the Art and Design and Performing Arts disciplines than we detected in the other disciplines that were part of our study (Little et al, 2009, p.38)

This small-scale research project set out to explore the experience of student:tutor relations in higher education in an art and design context. As Ashwin (2009) points out, the fundamental condition of higher education is that there is a relationship between teaching and learning, they are inextricable, and yet subject to numerous conditions which influence and impact the success of learning activities. ADM subjects rely on continuous interaction between students and tutors to promote learning and this ‘kind of exchange’ (Shreeve et al, 2010) is actually poorly understood and increasingly under threat from funding pressures and requirements to increase efficiency in HE. Research based on transactional analysis claims that a relationship in which students are treated ‘adult to adult’ is more conducive to learning (e.g. Mortiboys, 2005), but what are the stresses and strains in current studio teaching environments that might lead to less productive learning and teaching relations for students and how might we circumvent them?

Project Methodology

We adopted an appreciative enquiry approach (Cousins, 2009) to investigate the qualitative experience on student and tutor interactions in a range of art and design subject areas and levels. A framework of semi-structured interview questions was trialled and modified for use with tutors and for students. This enabled a common approach, yet allowed for unexpected avenues of enquiry to be developed if there were openings in the interview process. It began by asking for good learning experiences between tutors and students to be described, where possible giving concrete examples of interactions and outcomes. Students were employed to interview students in an attempt to remove the potential power imbalance in the interview relationship and to enable students to talk freely without fear of loss of anonymity. The student interviewer sent audio files to the researchers without names, or courses identified. The university ethics committee also advised a similar approach to interviewing where Ray Batchelor, as a fellow academic, rather than the Head of School interviewed staff who volunteered to take part.

We were aware of limitations with this methodology, but reporting through an interview process, a second order generation of data, does have advantages in that it allows a personal account and interpretation of the experience to be told, which an observation interpreted by a non-participant does not allow. More complex data generation for learning and teaching situations can be hard to manage and limited in numbers participating (for example see Mann, 2003). We experienced logistical problems in obtaining and managing the student interviews in spite of support from the student union. Timing was difficult with students absent when tutors had time to chase up progress!

The number of interviews (7 students and 7 tutors) was relatively small, but as it consisted of rich data about individual experiences we considered it to be significant enough to draw some general observations which would have resonance with art and design studio- and workshop-based subject areas more widely.

Outcomes including deliverables and dissemination strategy

The data was analysed thematically and several theoretical positions considered in deciding the final approach, including Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1998, Drew, 2004) and activity theory (Engeström et al, 1999). However, we agreed on a thematic analysis which began by categorising the topics raised by tutors and students in the separate interviews and locating overlaps in the topics and also identified issues which were not raised by one or other of the groups.

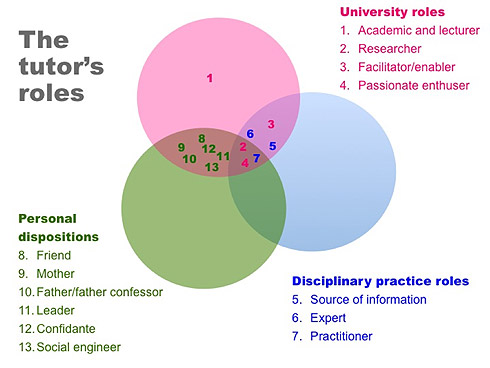

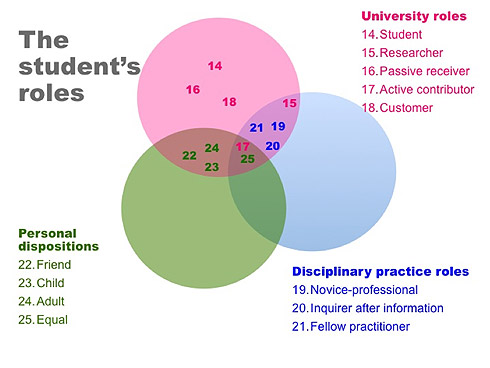

These categories were further located together under headings which we perceived to be particular identities shaped by roles structured by the university, the professional practice (subject area) of the participants and personal experiences or dispositions which they brought to the learning and teaching encounter (Billett, 2001).

Diagram 1

Diagram 1: The tutor’s roles: Fluidity and ambiguity have been the distinguishing characteristics of our findings. So, for example, being a ‘Passionate enthuser’ (4), might be taken as just a personal disposition and also, perhaps, an asset for a professional practitioner. In the context of student-tutor relations in a studio discipline it has a further value, as a key aspect of the role which the university expects the tutor to perform and an important influence on learning relations for the student.

Diagram 2

Diagram 2: The student’s roles: It should be noted in both diagrams that categories were arrived at on the basis of what tutor or student interviewees reported about themselves (or peers) and their roles. Although some student-tutor relationships (Father-Child, for example) suggest correlation and reciprocation in their performance, others do not. We found little evidence that students’ expectations as ‘Customer[s]’ (18) were matched in art and design studios by tutors seeing themselves as ‘service providers’, for example. Mis-matches of expectation are among the characteristics reported of poor learning and teaching experiences.

Although it is doubtful that we fully answered the research questions we set out, we believe that we have gained valuable insights into the highly complex roles that tutors play in supporting student learning in art and design. Although there is a greater sense of community in teaching and learning in art and design and more informal approaches than in other disciplines, we identified a series of areas where ambiguity exists and which are subject to forces which might upset a balance in relations. These imbalances could impact the success of dialogic learning encounters described by students and tutors.

Indeed, despite the limited number of participants and modest original research objectives, both researchers – experienced art and design academics – were much struck by the richness, complexity and variety of insights this project has highlighted. The effects on student-tutor relations of location and contexts, for example – contexts beyond the confines of the studio; roles which have multiple origins, and multiple values attached to them, so that in their performance, they are differently understood by the other, or others in the relationship. These also refers to relationship models themselves and consequent expectations which are, or are not, shared. This layering and interweaving of roles and relationship models which, partly from its sheer complexity, ambiguity and fluidity, when it goes wrong can work against effective learning and teaching, can equally be the hallmark of the best and most effective learning and teaching in a studio context. Such richness deserves further investigation.

Outcomes

1. The first outcome was the presentation of a short paper to the annual Society for Research into Higher Education conference in December 2011. This focused on the tutor’s experience of learning relationships. Whilst recognising that relations are of necessity fluid, dynamic and interdependent (Ashwin, 2009), we had analysed the outcomes as separate perceptions of experiences, and the research design did not enable us to match tutor with student in one encounter. However, we were surprised to hear about the range of learning activities which tutors deemed to be successful. These not only included the one to one encounter, which might be seen to be a gold standard in art and design, but included off site learning on live projects, summer schools, trips and visits as well as student-led discussion groups with the tutor absent! A wide range of situations was reported by tutors, but individual discussion was valued by most:

Factors deemed by tutors to have an impact on relations were varied and included:One to one tutorial is fundamental, tailor made – you need the body to cut it so it fits, therefore you need a one to one tutorial.

Demographics and biographies:

- gendered relations and the sex of the tutor, particularly in relation to the discipline norm

- age influences and differences including mothering or parental aspects of relations

- identity and status of the tutor including credibility in relation to the subject area.

Conceptions of learning and teaching in the discipline:

- tutor expectations of the student including being prepared for the encounter, interested in the subject and prepared to take ownership and responsibility for their learning

- tutors’ expectation that learning in art and design is not didactic, but open-ended, individually focused and about realising the potential of each student.

Barriers to good learning relations from the tutor’s perspective:

- time constraints

- workload - admin

- poor physical spaces for tutorials

- different cultural expectations of the learning relationship

- students wanting their practical work to be liked

- students uninterested and not taking responsibility for their own learning.

The overall context for good relationships in learning was the notion of professionalism, or ‘levelling’, so that there was a two way exchange embedded in respect. Underlying this though were some issues of power. Inevitably the tutor was more experienced and knowledgeable about the subject and was also in control of the assessment process, which automatically made for imbalances which those tutors interviewed were very consciously attempting to counter. It was also evident that, as researchers, we could see that power was being exercised, with good intentions, to ‘socially engineer’ situations, for example to bring a group together or possibly to ensure that there was cohesion in approach to a live project. Where there were some concerns we wondered whether the expectation by tutors of certain kinds of knowledge, awareness and experiences in new students might lead to lack of cultural capital in learning encounters for some students.

2. The second outcome was a paper which was accepted for the Design Research Society’s (DRS) annual conference in July 2012 where it will be delivered to an international audience of design educators and published in proceedings. We may also consider submitting this to a journal, depending on the requirements of DRS. The title of the paper is ‘Designing relations in the studio: ambiguity and uncertainty in one to one exchanges’. It examines the areas of interaction which have potentially hidden rules of engagement and which may be subject to ambiguous meanings and encounters. These have been categorised as relationships pertaining to:

- Professionalism

- Mother/father/child/adult

- Friend/guide/enabler

- Dependent/independent

- Expert/novice

whilst recognizing that there was constant fluidity in relations between student and tutors which structure tutors to take on different roles according to circumstances.

3. Materials have been created for workshops with students and tutors to help understand perceptions and to debate issues arising from the data. These will be made available to the HEA Resources site. They are suggestions for a format to enable discussion and interaction using statements made by participants in our research interviews. The tutors’ workshop is based on three issues starting with a discussion and exploration of tutors’ expectations entitled ‘What works best for you?’ This helps to set the scene and to make explicit the usually tacit requirements of participation in studio based learning activities. The workshop then uses the student and tutor quotations selected from appropriate categories in order to stimulate debate about creating adult-to-adult relationships, what might challenge these and how to best maintain them. The final exercise is to explore how a professional relationship is maintained, how the boundaries of friendship and respect might differ and what is appropriate in individual circumstances.

For students the workshop begins by asking ‘What does your tutor expect of you?’ This may be particularly important for students new to an HE environment, where the pedagogic practices are different to those previously encountered. It then takes a similar format to the tutors’ workshop and explores what students and tutors have said and provides the opportunity for the facilitator to offer guidance and suggest courses of action as appropriate.

Workshops are supported by an introductory PowerPoint presentation which briefly outlines the project and its intentions, quotations from students and tutors to stimulate debate, plus suggestions for further reading aimed at tutors.

4. Videos for student representatives to use as part of the engagement in workshops have been delayed and are running behind schedule. They are scripted but require processing. We aim to complete these by the end of May and upload them with the workshop materials. The intention is to dramatise and make accessible some of the issues which can affect relations for learning.

5. The Evaluation Report has not been completed as indicated on our brief due to the relocation of our evaluator to another institution.

Contact information

Alison Shreeve alison.shreeve@bucks.ac.uk

Ray Batchelor ray.batchelor@bucks.ac.uk

Biographies

Dr Alison Shreeve is currently Head of School of Design, Craft and Visual Arts at Bucks New University. Between 2005 - 2010 she was the Director of Creative Learning in Practice Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CLIP CETL) at the University of the Arts London. CLIP CETL developed knowledge and understanding of innovative and effective teaching in creative arts and created a wider awareness of these through development activities.

A teacher in embroidered textiles for over 20 years, Alison has a Masters in Art Education and a PhD in Educational Research from Lancaster University. Research interests include the student and tutor experience in creative arts higher education. She is associate editor of the journal Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education and a National Teaching Fellow.

Dr Ray Batchelor teaches Visual and Material Culture to students in the school of Design, Craft and Visual Arts at Bucks New University. He is the school’s learning and teaching coordinator and currently Lead Teaching and Learning Coordinator for the Faculty of Design, Media and Management. His passions include using new technology to support teaching and learning and the Argentinean Tango.

References

Ashwin, P. (2009) Analysing Teaching-Learning Interactions in Higher Education, London & New York, Continuum.

Billett, S. (2001) Learning through working life: interdependencies at work. Studies in Continuing Education. 23(1): 19-35

Cousin, G. (2009) Researching Learning in Higher Education, New York and Abingdon, Routledge

Drew, L. (2004) ‘The experience of teaching creative practices: Conceptions and approaches to teaching in the community of practice dimension’. In A. Davies (Ed.) Enhancing curricula: Towards the scholarship of teaching in art, design and communication, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference, London, Centre for Learning and Teaching in Art & Design, pp.106–123.

Engeström, Y. Miettenen, R. & Punamaki, R. (1999) Perspectives on Activity Theory, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Mann, S. (2003) ‘Inquiring into a higher education classroom: insights into the different perspectives of teacher and students’. In C. Rust (Ed.) Improving Student Learning Theory and Practice – 10 years on. Proceedings of the 10th ISL Symposium, Oxford, OCSLD pp.215-224.

Shulman, L. S. (2005) ‘Pedagogies of Uncertainty’, Liberal Education, 91, pp.18-25.

Sims, E. and Shreeve, A. (2012) ‘Signature Pedagogies in Art and Design’. In Chick et al (Eds) More Signature Pedagogies, Stylus, USA.

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice. Learning meaning and identity. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Appendices

Introduction to workshops - project context (pp presentation)

Workshop for students in art and design

Diagrams 1 & 2 supplied by A Shreeve and R Batchelor

Header image: Section from a photograph of George J. Lober among a group of eleven fellow sculpture students. Circa 1911 or 12. Published in: Archives of American Art Journal v. 12, no. 2, p. 23. : Unidentified photographer. Sourced from Flickr commons

Back to Art Design Media Learning and Teaching Projects 2011-12 - Final Reports