Towards globalising: peer communication of creative practices

Harriet Edwards, Royal College of Art

Developed from a practical strand of recent PhD research (‘Design Leads’), this article outlines a series of drawing activities that offer a way into peer exchange and articulation of creative practices. While activities transfer to various teaching and learning contexts, this article centres on international students preparing for postgraduate studies and calls on tutor and student commentary ...

Keywords: drawing / visualising, creative practice, integration, communication, writing

Abstract

Developed from a practical strand of recent PhD research (‘Design Leads’), this article outlines a series of drawing activities that offer a way into peer exchange and articulation of creative practices. While activities transfer to various teaching and learning contexts, this article centres on international students preparing for postgraduate studies and calls on tutor and student commentary.

The activities produce a relaxed environment in which to see with fresh eyes through drawing. However much drawing may appear out of kilter with today’s digital practices, I intend to show how potent it can be in encouraging a sense of a community of practice while increasing students’ awareness and confidence in capabilities and approaches. The drawings stimulate curiosity about peers’ experiences across individual practices, disciplines and nationalities. Further, resulting discussion offers leads into written texts - somewhere between reflective and expressive.

‘The true method of knowledge is experimentation’, William Blake.

A brief

The challenge: how to plan for a multi-national, multi-discipline group of students mostly in their twenties on the RCA Pre-sessional? In 2011, there were 12 nationalities (60% from the Pacific Rim) and 12 disciplines – mostly on the design side but including a few fine art students. The students have excelled in creative practices yet are admitted to the RCA pre-sessional course because they have not quite made sufficient progress in terms of linguistic ability, often writing. How to plan a course to suit student needs and maximise their potential while they are immersed in London/UK/art and design studio-based culture? How to create a sense of motivation and confidence regarding linguistic skills that will sustain students through studies in the medium of English?

English for Academic Purposes (EAP): one particular angle

The curriculum we devise in EAP is not purely linguistic but rather indivisible from cultural and social dimensions connected with integration, orientation, identity and affect. The history of language learning since the 1960s is too complex to detail in this short article: suffice it to say, our emphasis is student-centred with students’ own backgrounds and experience employed as resources. Overall, we maintain an eclectic approach and produce a multi-layered syllabus.

The majority of our students are design-oriented, and 60% from the Pacific Rim. They do not arrive with an articulate, western-based command of the relative aesthetics, say, of some fine art cultures. Academic writing can be problematic, with a reading-centred plethora of academic literacies the sub-skills for which are multiple and not always transparent (Joan Turner, 1999). The EAP course reviews, extends, emphasises points of difficulty, and maximises practice opportunities, but cannot prepare students fully for the onslaught of accents, slang, cultural references whether from the streets, TV, postmodern theory, or indeed the London music/art/ design scene that hit students when beginning MA programmes.

Figure 1: Influences

Is the ability of such students to engage in city, English and college life under-appreciated? How much does the university culture allow for the ‘small narratives’ (Lyotard, 1984) of its international community on which it is dependent, or, to put it another way, how ‘global’ can it be? The course I describe below offers one way of encouraging the voices of a community of practice across differences.

Background perspective on the ‘Drawing, Speaking Writing’ activities

As a team member of Writing Purposefully in Art and Design (2002-6) I joined in discussion about writing practice and provision; dyslexia issues and insights, and how to respond to the rapidly changing digital technology together with a set of pressing economic factors. All of these were debated across the network and recorded on www.writing-pad.ac.uk, which still has a set of resources on it, mainly with undergraduates in mind.

The website’s resources are somewhat divided between the promotion of ways in which art and design students might be better trained, say, to deal with the reading and writing culture of degree programmes (a cross-over with EAP aims), and an emphasis on the distinct student identity towards the defining of a visual or practice mind (Raien, 2003, Davies and Riley, 2011). Hybrids or forms of creative practice thinking seemed to disrupt the more conventional, academic text-based culture, and through doctoral research, I intended to pursue this area in depth. As the research project developed, I devised a series of ‘drawing and writing experiments’ that took place in six institutions across the network (details in ‘Design Leads’ Ph.D. 2011).

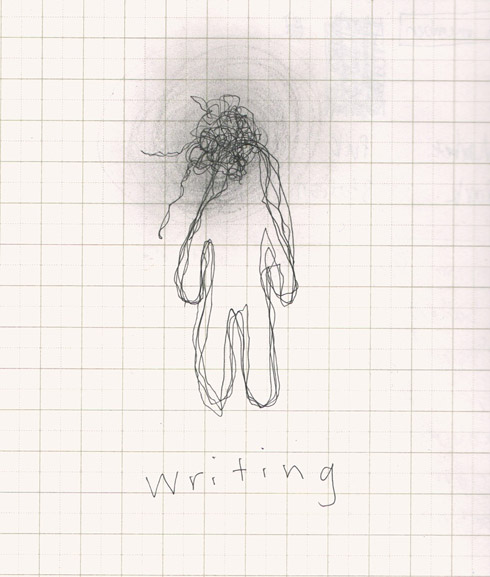

Figure 2: Writing

The setting up of the ‘Drawing, Speaking and Writing’ activities

The book that emerged from doctoral studies, ‘Exercise, a little book of drawing and writing’, was trialled on the pre-sessional course 2011 where it served the 33 studio-based students preparing for MA programmes, mainly in design with some in fine art.

Instructions include drawing the ‘habitat’, ‘practice moves’, ‘the brain’, ‘the hand’, ‘being lost’ and the like. Each session is simple to set up (minimal lead-in, maximum space for activity) and is introduced by key questions or anecdotes from previous interviews/experiments. The tutor acts as facilitator, sometimes participant: handing out materials, feeding in, engaging students in activities, managing time and points of feedback. After a response in drawing of around 15 minutes or so, there is a conversational exchange around the drawings, then an extension of the communication in writing with general group feedback at the end.

None of the individual elements could be said to be original in themselves. There is obviously a similarity to drawing activities in practice contexts and on the other hand, to brainstorming or mapping as a prelude to writing. The activities lend themselves to a gallery-like exhibiting of sketches, as well as to a discussion over work not a million miles away from a critique, a peer-operated one.

What is difficult to convey in this article is the quality of what occurs within such an environment, towards the intelligent over the intellectual. It is in part sensual: the informal space in the room, the smell and touch of paper, the visual focus. It is in part kinetic: a movement of paper and material, a movement across the room to others’ works, to the exhibiting. It is also definitely affect: the buzz at a new venture, the nervousness at beginning, some surprise at what comes up, with that, enjoyment, though the activity sometimes raises difficulty of course: blocks, puzzles, fears, and challenge. Sometimes, a silence descends that is made from concentration and absorption. Steven Farthing (2011) says that drawing captures ‘multi-dimensional events’: in this case, there is multi-dimensional experience too.

‘What did you think when you first did the drawing exercises?’

Despite my apprehension about how the course would be received, the student feedback was copious and extremely positive, providing much food for thought. I will therefore cite comments [including small errors] from just two out of six feedback questions, dividing each into sub-themes with subsequent commentary.

AWKWARDNESS

‘I don’t know what I’m going to do. A little bit confused about the logic.’

‘I had to understand what it was all about … but after some days, it was clear, very useful.’

‘In the beginning I feel confused but after I do it I gradually start to experience the chemical and magic of doing these exercises. Especially when transforming the drawing into writing. It feels like sorting out logics in our abstract thinking.’

There was a gamble involved in tutors knowing how much to explain at the start. While such explanation is generally seen as good teaching practice, it can pre-empt students’ own direction and discovery, and inhibit openness of response. The students’ initial immersion, however, creates awkwardness – a sense of difficulty and tension to be worked through that I came to see as inevitable in practices, though not desirable.

I was surprised, however, by the explicit reference to ‘sorting out logics’, something I had not anticipated but that was endorsed by others’ comments. Steven Farthing (2011) also comments on the making sense and organising that derives from drawing origins in a process of simplification though interestingly, he refers to drawing alone while in the above case, this seems to transfer to writing.

INTRIGUE AND SURPRISE

‘I never did it before and it was interesting.’

‘Well, that’s different and it could be good, especially for visual creatives.’

‘I think, I didn't know why we did that so I was interested…I mean curious.’

The course was able to capitalise on the creative instinct to try things out and go for the new. This was ironic on one level as all the themes for drawing came originally from interviews and experiments with students, designers and tutors about their own practices. I imagine that the way in which the three activities of drawing, speaking and writing were joined together made the ‘difference.’

THE UNPREDICTABLE

‘I was thinking to myself that something different would happen but I couldn’t predict what or how it would go on, but I was very happy because I didn't like to start from writing.’

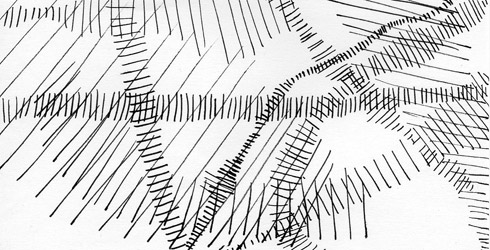

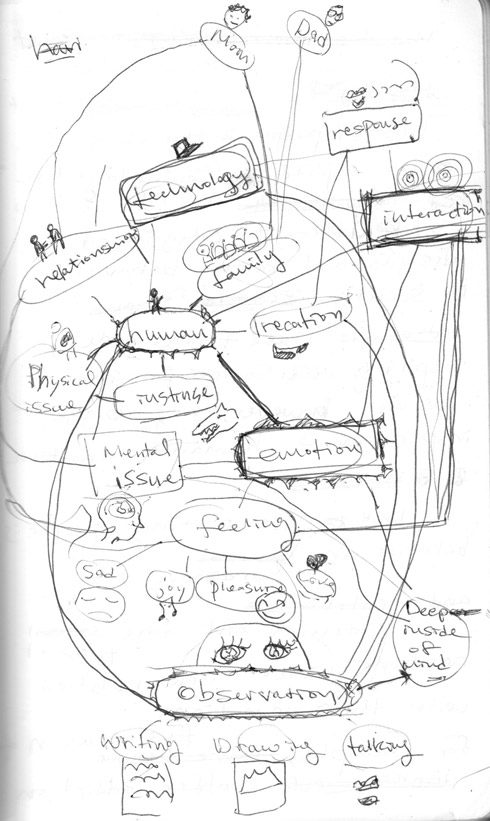

In retrospect, it appears that distinct kinds of thinking were going on in the initial activity: I propose that some students were more logical thinkers, producing more diagrammatic images, while others responded in impressionistic ways, or more intensely visual ways. In the latter case, it might be appropriate to talk about ‘visual thinking’ i.e. something more unconscious that needed a ‘translation’ to words. The indirect movement to writing from drawing seemed to suit many students and was endorsed by Helen Elder, participating EAP tutor, who described that movement as more flowing over time.

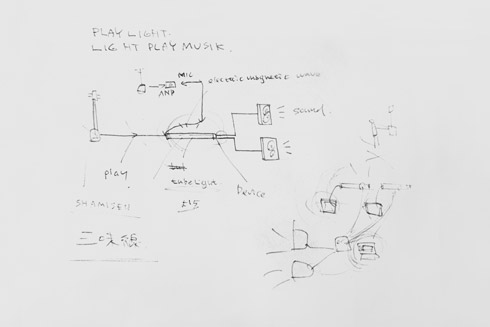

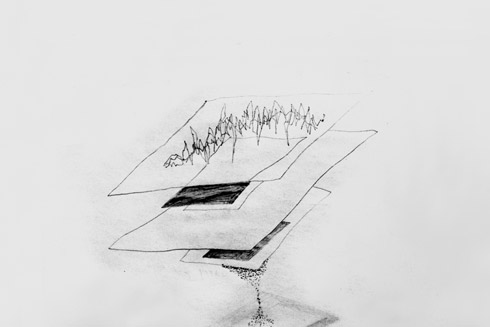

Figure 3: Diagrammatic, process

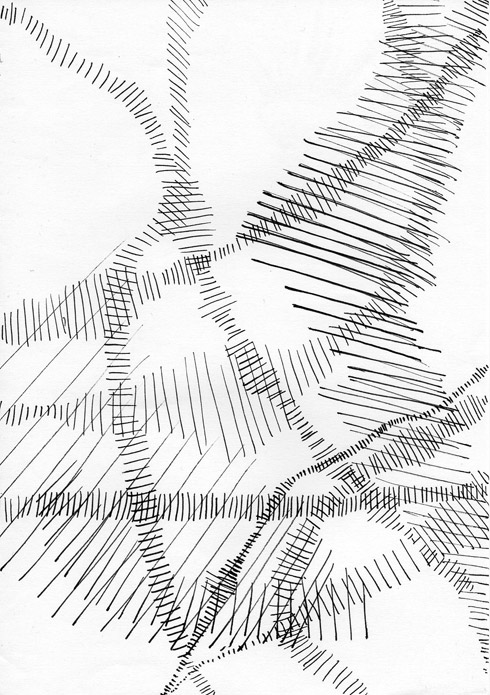

Figure 4: Impressionistic, time

PLEASURE

‘It’s exciting me. I like to practice.’

METHOD

‘At the beginning I didn’t get the meaning of the project. But after using it, now I am realising the potential and the possibilities of the method.’

The activity was treated as very much hands on and tutors deliberately avoided theorising or speculating about what might happen in advance with students. It was interesting therefore that students referred to ‘method’, something I had been reluctant to do myself. It was a means of ‘sorting out logics’ and ‘useful to build structures of the writings’. While this could be due to the dual benefits of looking back through visualising and reflecting, the visualising appeared to be the more profound enabler.

‘What was the experience like of drawing around aspects of your creative practice?’

SPONTANEITY

‘I never tried to draw a thing in such a short time. So it is a challenge and I find it useful. (Normally I need to decide for a long time before I draw).’

In my own experience, some of the richest drawings were the very fast ones, done without too much deliberation or perhaps, conscious interference. Partly that would depend on subject matter but it is a phenomenon described vividly by Jane Graves when she wrote about ideas coming up out of the dark, aside from the clutter of the mind (2009). I would further describe it as primary, giving way to other kinds of slower development.

AS AN EXERCISE

‘It was helpful, because it was like a warming up process before having sports. The drawing task made me orient to the particular topics.’

‘I couldn’t really be creative the first time, it had been too long time I didn't try to draw with my thoughts because in general, I usually draw the sketch of my ideas.’

‘I like the subject, which is abstract and conceptual to draw. However, it gave me lots of inspiration and space for thought again. Think that I will keep this method in the future as well.’

Here is an acknowledgement of difficulty again, along with the assertions of postgraduates’ own drawing purposes and methods that are distinct. It could be argued that the exercises were too manipulative but there was in parallel, the surprise element, an indication that the struggle was worthwhile, and for one at least, a new way into thinking. As Betts emphasised, drawing can be a ‘tool for research, reflection, analysis, investigation and experimentation’ (Kantrowitz, et al, 2011).

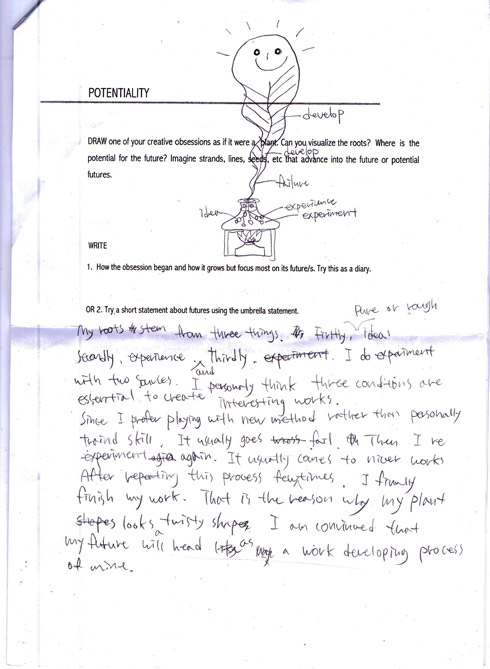

Figure 5: Potentiality

Figure 5: Potentiality

A LANGUAGE COURSE?

‘I was shocked, don't know why even a language course has to draw.’

‘I think it was an interesting way to improve my English.’

‘I think the first time is quite new and exciting for me. I love the idea or way that this exercise is so different from other language course.’

The first and last comments speak volumes: our education systems generally present creative and linguistic courses/pedagogies as separate, two separate spheres. The Exercise book attempted to bring the two spheres together in a kind of crossing over procedure articulated below in ‘A bridge.’ The drawing meant beginning with the students’ familiar, their identity, but the focus on visualising created sources from which students moved to ‘secondary’ thinking. In this respect, I am calling on theories of left and right hemisphere, signposted at the end of the article.

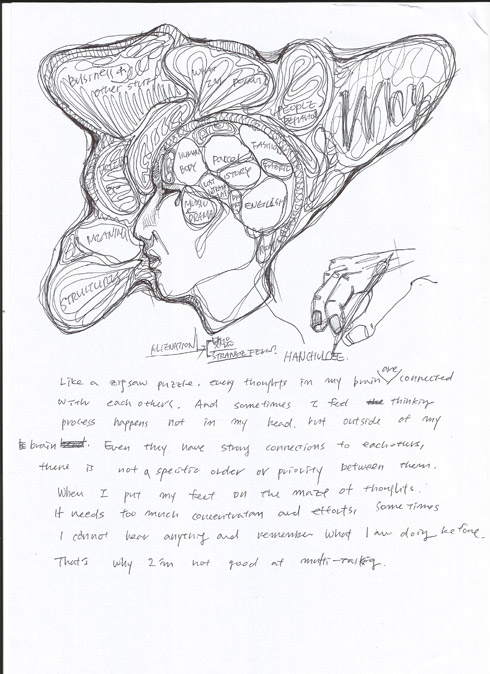

Figure 6: The Brain

Figure 6: The Brain

A WAY INTO WRITING

‘It’s so different from the way I learn writing. But it is really interesting to think it carefully before writing.’

‘I thought it was a bit strange in the beginning but it also made sense and I got used to this way of ‘experience writing.’

‘Thought, why didn't I learn this writing in such a way in the beginning of my learning…I thought this method is so helpful.’

A BRIDGE

‘It’s like finding a bridge between left brain and right brain, I think. Actually, it’s different way of thinking and structuring things, but it’s like we’re trying to make it united, as seamless as possible.’

Does ‘trying to make it seamless’ refer to the kind of automatic or unself-conscious process that goes on when we move from a drawing sphere to a writing sphere? Is that a ‘globalising’ kind of framework? It certainly connects to the ideas of Iain McGilchrist (2009) that I refer to below.

EXCHANGE OF PRACTICES AND EMPATHY

‘It was like explaining my secret world.’

‘I was inspired by other students’ drawings and their roots. It was absolutely different although we drew the same subjects.’

‘It makes me realise the difference between us. It allows us to enter in a way in people’s mind and discover then maybe more personally.’

The sessions remained non-competitive, which made them ideal, away from the more aggressive (self-promoting) stance necessary for assessments, applications, internships and job searches. The realisation of ‘the difference between us’ makes for a consensual stance and a sense of space. A similar effect is pinpointed by Betts quoting Farthing on drawing as common property: ‘it implies a democracy of use and purpose and removes a perception of hierarchy or belonging to one discipline’ (2011).

Yet about ‘explaining my secret world’, I profess ambivalence. Why not a secret world? And if you tell all, how or what can you make? Is the energy for that diffused?

IMAGINATION

‘Strange. We were asked to draw about things we never drew before. It is a process that wake up your imagination.’

‘It’s a journey to loose myself and experiment what I think. Through the journey I am more confident and open another door for me to creative my drawing.’

DRAWING ACTIVITY AS GOOD IN ITSELF

‘Fresh try!’

‘Drawing exercises were good as ready practice for actual drawing.’

‘Helpful to make my horizon broader. I was able to realise more.’

‘Sometimes it was helpful. I think it develop our abstraction skill.’

‘It was great! I start to use different point of view to think and different ways to draw.’

REFLECTIVE INSIGHT

‘It can give me an opportunity to have a look at my past and think about my work objectively.’

‘Very good. Because I could concentrate and think to most of the other things that I did accidentally and automatically before. So I could understand my nature and my spirit better and how the pieces would start to continue in me. *You make me clear to myself. *’

Figure 7: Practice pattern

Figure 7: Practice pattern

The potency of the drawing, speaking and writing activity

While the limits of this exercise were reported as mainly limits of time, the strengths remain many:

- It offers ways into seeing with fresh eyes through drawing, speaking and reflecting on creative practice, as well as into written recording.

- Students are able to orientate themselves in relation to practice in what appears a genuine, honest manner, owning their approach.

- There is an appreciation and awareness of difference across practices and nationalities plus a sense of community through the non-hierarchical peer exchange.

- While the Exercise book includes prompts into writing, the writing activity ‘seemed to flow naturally’ without any additional input.

- Beyond the process of writing, a plethora of outputs emerge: notes, a list or map or cartoon, a small objective report, a narrative, a voice to perform, a poetic text, a nugget for future unravelling. What should be stressed is that these were individual texts arising from ‘experience writing’, as one student put it.

- If the tutor joins in, they offer part of their own experience of practice in a more horizontal, shared way.

- The students gather by-products of seeds for the future, as do tutors while gaining insight into this fundamentally holistic approach.

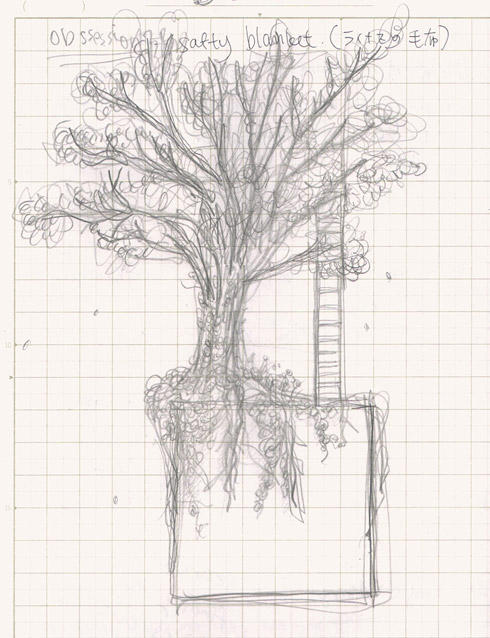

A central influence

There are many influences on Exercise that have grown through the research period and up until now, with the recent publication of Thinking through drawing practice into knowledge (2011). One enormous impact for me was The Master and His Emissary (2009) by Iain McGilchrist. Despite an impressive referencing of neuro-scientific findings, it was his cultural view of the hemispheres and their roles that made the lasting impression. His explanation of their interaction, and above all, his argument about the harm done by the dominance of the ‘left hemisphere’ in western society was persuasive. In terms of the position of drawing to writing via speaking, it seems to me there is clearly a ‘bridge’, a movement from the primary source expressed in drawing through to the secondary of writing, as one student said:

‘When it comes to writing after the drawing, it’s like we are elaborating or articulating or explaining our work in a logical and comprehensive way. It’s like interpreting ourselves work [sic] and make it understandable to others and ourselves as well.’

Figure 8: Tree-ladder

Figure 8: Tree-ladder

Finally, having emphasised one role of drawing in Exercise, I would not wish to deny its potency in many other ways and for its own sake.

Towards globalising

First, with ‘towards globalising’, I have the holistic in mind, which although worn, still usefully describes a multi-dimensional activity such as drawing, speaking and writing, with distinct kinds of cognition brought together in an environment beyond individual-with-screen.

Second, ‘towards globalising’ means integrating individuals themselves from many places and educational systems in the attempt to diminish what I see as ‘eastern’ and ‘western’ splits in the community. If discussion begins with students drawing and articulating, a positive atmosphere is generated, with a more democratic exchange of experience and more understanding.

Thirdly, ‘globalising’ refers to the ‘two-hemisphere’ integration through drawing, then speaking and finally writing – metaphorically at least, a move from right to left hemisphere that will be expanded on in my next publication, ‘An account of Rhythms of Practice’. Simply, ‘towards’ signifies that I am still wondering about this whole area. I remain uncertain and probing, which I consider no bad thing.

Contact information

harriet.edwards@rca.ac.uk (you can obtain copies of Exercise at this email address)

Biography

Harriet Edwards is the English for Academic Purposes Co-ordinator and a teaching fellow at the Royal College of Art. Her work deals with international students as well as writing development at MA and Research level. Outside the main college role, she has run a number of experiments based on drawing and writing. She was a project team member of Writing PAD and is now assistant editor of its Journal of Writing in Creative Practice (Intellect). In 2011, she completed a PhD exploring how certain contemporary design processes might impact on higher education writing culture. The research project was realised through a studentship at the Landscape, Architecture and Design School, Leeds Metropolitan University.

References

Davies, M. and Riley, H. (2011) ‘The Visual Essay: Further Thoughts’, Writing PAD symposium, Friday, 1 April 2011, Swansea, Swansea Metropolitan University.

Kantrowitz, A. Brew, A. and Fava, M. (Eds.) (2012) ‘Thinking through drawing practice into knowledge’, Proceedings of an interdisciplinary symposium on drawing, cognition and education, Symposium: 28-29 October 2011. Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, http://drawingandcognition.pressible.org/files/2012/05/Thinking-through-Drawing_Practice-into-Knowledge.pdf, Date accessed 08/06/12.

Drawing Research Network (DRN). DRAWING RESEARCH, JISCMAIL@AC.UK, Date Accessed 06/06/12.

Duff, L. and Davies, J. (2005) Drawing: the process, Bristol, Intellect Books.

Duff, L. and Davies, J. (2008) Drawing: the purpose, Bristol, Intellect Books.

Edwards, H. (2011) ‘Design Leads: a re-evaluation of design thinking and making and its potential impact on HE writing culture’, Ph.D. School of Architecture, Landscape Gardening and Design, Leeds Metropolitan University.

Francis, P. (2009) Inspiring writing: taking a line for a write, Bristol, Intellect.

Graves, J. (2008) The secret life of objects, London, Trafford.

King, S. (2012) ‘Only connect: an integrative, participative approach to writing through film that promotes the experiential over the theoretical’, Networks 16, ADM-HEA.

McGilchrist, I. (2010) The master and his emissary: the divided brain and the making of the western world, New Haven; London, Yale University Press.

Moon, J. (2004) A handbook of reflective and experiential learning, London, Routledge.

Petherbridge, D. (2010) The primacy of drawing: histories and theories of practice, New Haven; London, Yale University Press.

Raien, M. (2003) ‘Where is the ‘I’?’ Discussion Papers, Resources, Writing Purposefully in Art and Design, http://www.writing-pad.ac.uk/, Date accessed 07/06/11.

Schön, D. (1983) The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action, London, Basic Books.

Turner, J. (1999) Academic Literacy and the Discourse of Transparency. In: Jones, C. Turner J. and Street, B, (Eds.) Student writing in the university: cultural and epistemological issues, Amsterdam; Philadelphia, PA, John Benjamins Publishing.

Writing Purposefully in Art and Design (2007) http//www.writing-pad.ac.uk, Date accessed 06/06/12.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to tutors, Helen Elder and Simon King, and all the pre-sessional students of 2011, especially those who volunteered images – Soomi, Han, Yuen, Yu Yu, Kaoru and Masayo.

Images: supplied by Harriet Edwards

Listing Image: Section from Figure 6, The Brain

Header Image: Section from Figure 4, Impressionistic, time