Facilitating Interdisciplinary Learning and Innovation in Games Art Education

Lynn Parker, Robin Sloan, and Santiago Martinez, University of Abertay Dundee

In March 2011, the Digital Arts Curriculum – Interdisciplinary learning and Innovation project (DACii) was launched at the University of Abertay. The aim of this project was to facilitate interdisciplinary learning and encourage innovative thinking amongst students of Computer Arts, with particular focus on the application of digital game design as a means of addressing research problems posed...

Keywords: curriculum design, game art; game design, interdisciplinary, technology

Abstract

In March 2011, the Digital Arts Curriculum – Interdisciplinary learning and Innovation project (DACii) was launched at the University of Abertay. The aim of this project was to facilitate interdisciplinary learning and encourage innovative thinking amongst students of Computer Arts, with particular focus on the application of digital game design as a means of addressing research problems posed by other disciplines. The project methodology and outcomes are presented in this article. This includes the findings of a student game design case study in response to a brief from environmental science experts and the results of research into curriculum design within a Computer Arts programme.

Introduction

DACii is a project hosted by the University of Abertay Dundee, a centre for excellence in Computer Games Education, and funded by the Art Design Media Subject Centre of the Higher Education Academy (ADM-HEA). The project aimed to promote arts-led interdisciplinary thinking within a game art curriculum, and to introduce concepts and methods that are not typically present in game design education. The overarching goal was to broaden the knowledge and understanding of computer arts students, with a view to producing graduates who are better equipped to contribute to and lead innovative, interdisciplinary projects.

The following aims and objectives were stated:

- to involve students directly in the development of a new curriculum for game art and design

- to facilitate interdisciplinary learning and experimentation with contemporary technologies

- to encourage students to engage with research issues that cross disciplinary boundaries and academic departments.

To achieve these aims, the project team undertook the following objectives:

- recruit a team of computer arts students for participation in a two-month team project, which will form the basis of a qualitative study

- design and deliver an innovative curriculum for 3rd year computer arts students that incorporates interaction with advanced technology

- hold an exhibition of project findings targeted at arts students and staff from higher education institutions.

Rationale

3D games technology is increasingly used by researchers and practitioners outside the field of interactive entertainment. Perhaps the most widespread application is in education, where 3D worlds and virtual agents are used to facilitate learning and complement assessment (Nazir et al, 2008). 3D training simulators have been developed which immerse users in virtual worlds, for example preparing soldiers (Ciavarelli et al, 2009) and emergency response teams (Backlund et al, 2007) for real world scenarios. More recently, 3D real-time graphics have been embraced by researchers in the natural sciences as a method of visualizing complex data and communicating concepts to stakeholders (Isaacs et al, 2010). This application of games technology for learning or to convey detailed information has typically drawn on technical rather than artistic techniques for producing 3D art. However, advancement in technology and the desire to display ever-more complex ideas in the form of 3D virtual worlds could greatly benefit from the input of specialist digital artists.

In all applications of games technology, the need for expertly crafted 3D artwork is high. Students of digital arts courses – particularly those which focus on games – are not typically exposed to artwork production for interactive visualization. A few specialist courses, for example forensic animation and visualization, offer cross-disciplinary learning for student artists. At present, programmes in game art and design tend to focus on practical skills needed for employment in the commercial games sector (e.g. Makila et al, 2009), with little or no insight into how their skill set may enhance research in other disciplines. Research into teaching of 3D graphics for visualization and simulation has been conducted (Brutzman, 2002), but thus far there has been no published research into the development of an art-led curriculum for interactive 3D worlds.

As competition between companies and demand for funding in the commercial games sector increases, it can be argued that students must have an enhanced awareness of the application of their skills in a wider context. As the games sector in the UK continues to slip behind competitors (Cowen, 2010), there is an increasing need for game art graduates with skills to drive the industry forward. In the case of the DACii project, the demand for artist engagement with environmental science research was explored, fostering an awareness of a potential area of sustainable development in the game art sector.

Project Methodology

The research was undertaken in two phases; the summer phase (a case study of a group project), and an evaluation of student engagement with a new curriculum design. The case study trialled arts-led interdisciplinary research with a group of Computer Arts students. The students were set a brief by the project’s partner department, the Division of Environment at the University of Abertay. Over the course of eight weeks, the students worked with scientists and technologists from across the university, before designing and prototyping an original game design concept. The case study was supported by a focus group involving the participants, and the results from the case study informed the second phase of the project – the curriculum design phase – where a new syllabus was implemented and evaluated. The findings of the project were presented in an exhibition at the SICSA (Scottish Informatics and Computer Science Alliance) meeting hosted by the University of Abertay Dundee in February 2012. Both external and internal staff and students were invited to this exhibition to review the project findings, meet participating students, and to try student prototypes from both the case study and curriculum phases of the project.

The Summer Phase Case Study

The case study was targeted to take place over the summer of 2011. It aimed to trial a number of innovative delivery methods with a small group of students and to promote use of emerging technologies to enhance student practice. The findings of this trial would be fed into the development of a new syllabus to be delivered to third year Computer Arts students in the curriculum phase of the project.

The summer phase engaged a group of six Computer Arts students who had just completed their third year of study. The group worked on an arts-led interdisciplinary project to produce a prototype software application for the Division of Environment and their external stakeholder. The task posed by the Environment partner concerned the design and development of an interactive media installation that would successfully convey the role of natural coastal defences to the community. The specific application was to communicate the need for defence barriers on the West Sands beach located in St. Andrews. The student group were exposed to a range of disciplinary contexts and approaches through a lecture series, field trips, and tutorial sessions. The project activity benefited from advice, input, and feedback from the partner department, who contributed expertise in environmental visualisation and provided a real-world problem for the arts students to work on.

During their development process, students were able to meet a range of researchers working within the University of Abertay Dundee, to gain insight into their research practices and field of expertise. Guest seminars were delivered by PhD researchers and academic staff who specialised in a range of fields, including promotion of soil sustainability, development of interactive virtual environments, human-computer interaction, and cognitive psychology. These guest seminars were complemented by art and design focussed lectures delivered by the project team to inspire and aid the development of an artistically pleasing prototype. Students also attended technical tutorials, delivered by a technical assistant. Lastly, the students were able to visit St. Andrews West Sands to meet the beach ranger and a representative of the Countryside Trust (see Figure 1), who are working closely with the University to tackle the communication of the problems associated with costal defences to external stakeholders. The field trip offered further insight into the problem the students were hoping to address and also allowed collection of vital information and image research to enhance the visualisation of the final application.

Figure 1

The final prototype that the students conceived made use of emerging digital technology (multi-touch screens and stereoscopic 3D) in order to engage users. The interactive prototype was designed as a vehicle to allow student experimentation with new technologies, to trial new teaching approaches, and to build on interdisciplinary project development. The finished prototype was very well received by the partner department and their external stakeholders, and follow-on funding has been secured to continue this collaboration, leading to a more fully developed game based upon the summer phase prototype.

Upon completion of the eight week development phase, the student group were asked to write a short report of their experiences and to attend a focus group to discuss the project in more depth. The output of this qualitative research was analysed by the project team and the findings were used to inform the delivery of the second phase of the project; the curriculum phase.

Curriculum Phase

The curriculum phase was delivered within a one semester core module from the third year of the BA (Hons) Computer Arts programme. In total, 47 students undertook this module as part of their core game art education. The 'Advanced Interaction' module was historically a game art production module, where students were required to produce 3D interactive environments for a ‘Triple A’ game title. Lectures and tutorials focussed on the development of a game prototype and relied heavily on game trends and the popularity of first person shooter games. The technical elements of the module remained in the revised curriculum. However, the project brief and lecture content was shifted to conceptualizing and designing an original 3D virtual environment in response to a targeted research question based upon five core non-games applications of interactive technology.

The module was delivered by Computer Arts and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) experts with support from Psychology, Engineering, and Environmental Science specialists. A more conceptual approach to technology was applied, allowing students to prototype innovative concepts without being hampered by limitations imposed by a lack of specialised technical skills which would often be provided by specialist programmers within professional projects. The student group worked towards design concepts rather than functioning products to develop more innovative digital art solutions using a variety of complex technologies. A conceptual approach allowed the student to be creative in their application of technology but to present their designs in either illustrative or interactive forms without technical limitations.

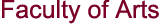

Students were required to devise a research question around five core non-games applications and to develop research skills and understanding in their chosen area. The student group developed personal research agendas based on topics as diverse as virtual commerce, interactive gallery spaces, energy use in the urban environment, and airport navigation (see Figures 2 and 3 for examples). The questions they identified correspond to real-world problems, in line with the nature of the summer phase of the project.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Upon completion of the curriculum phase, the student group were asked to complete a short survey detailing their experience of the module and its impact upon their creative development. This provided quantitative and qualitative data for evaluation of the project.

Project Findings: Summer Phase Case Study

Analysis of the summer phase focus group transcript highlighted four major themes that were used to inform the new game art syllabus trialled within the curriculum phase:

- expansion of the context of Computer Arts practice through interdisciplinary collaboration can enhance creative development

- active learning through field trips, brainstorming, discussion groups and regular formative feedback can enhance student engagement

- discussion of, and exposure to, new digital technologies helps stimulate innovative design solutions

- the requirements of an interdisciplinary digital design brief may drive individual technical development.

The curriculum phase of the project was designed around these findings and the observations of the project team during the project. The coursework specification of the ‘Advanced Interaction’ module was re-written to require that students compose a research question to drive their creative work, and that the research question must relate to one of five non-games core themes:

- an interactive visualisation for science, engineering, or technology

- an interactive service for navigation, travel, or tourism

- an interactive social, commercial, or financial application

- an interactive educational or training tool

- an interactive documentary or story

These areas were chosen to challenge students’ interpretation of interactive media and to promote expansion of student theoretical and technical practice through interdisciplinary research. The lectures delivered throughout the module were written by a range of specialist staff to ensure interdisciplinary input and the classes themselves were planned to be delivered by both HCI and arts staff to promote further collaboration.

The brief was also developed to take a more conceptual approach. The production of working prototypes requires advanced technical skills beyond the remit of arts students at this level, and so emphasis should be placed on conceptualisation and design. A key finding from this process was that the participants highlighted tutorials and lectures relating to non-game art fields as being the most informative to the development of their creative practice.

The six students who participated in the summer phase of the project are now completing their honours year research projects and a number have clearly been influenced positively by their experiences of the project. Two students chose to undertake multidisciplinary research working with augmented reality and stereoscopic 3D to address real world problems outside the field of game art.

Project Findings: Curriculum Development Phase

Findings from the curriculum phase survey were very positive, although response was lower than anticipated with only 50% (n = 22) of the class responding to the survey. The results suggest four key enhancements for the student group through the revised curriculum:

- enhanced understanding of research projects and proposals

- enhanced design skills both for different users and different technologies

- engagement with areas beyond entertainment games

- more prepared for multidisciplinary team work.

Overall the majority of students felt more equipped in terms of research processes in relation to their own specialist field and to mixed discipline projects. Over 82% of respondents believed their research processes, in terms of art and design research projects, were enhanced by the project and 91% believed that they now have a better understanding of fields other than Computer Arts. Of the respondents to the survey, 68% feel better prepared for multidisciplinary team-work which impacts positively on their practice both during their studies and upon graduation. In terms of creative practice and the role of the arts student, 78% felt better equipped to design applications with users in mind. In terms of HCI, usability, accessibility and interaction design, 63% felt that innovative uses of digital technology encouraged them to be more creative in the development of design solutions. This feedback suggests that students feel more technically and artistically equipped for the production of interactive applications through studying this curriculum. 91% of the student group agreed that they have a better understanding of how interactive digital media can be used in areas beyond entertainment games, and 78% felt that the module helped them to engage with areas other than Computer Arts. This suggests that students are more aware of their own role as a creative practitioner in the design of an interactive product, whether for an entertainment product or a non-games application, and that a high percentage of respondents are now more engaged with working more broadly with interactive art.

Dissemination Strategy

Throughout the project, a blog has been maintained with updates on project activity and findings. This record of the project also hosts the project documentary which is a ten minute film detailing the delivery and findings of the DACii project. The blog can be found at the following address: www.dacii.blog.com

An interim exposition of the summer phase was undertaken in August 2011 (see Figure 4) with staff and students from the university along with our partner department and external stakeholders in attendance. The exposition saw a presentation of student process and a trial of the working prototype for feedback and development. This exposition enabled the team to present the prototype to stakeholders in a professional manner, and the game concept has since secured funding for further development and deployment.

Figure 4

The final project exhibition (see Figure 5) was hosted as part of the SICSA event in the University of Abertay Dundee, on February 29th 2012. The exhibition was advertised to staff and students from universities around Scotland and also to those involved in SICSA. The exhibition promoted the project findings through a project poster, programme and four student prototypes on show for visitors to try. The project documentary was also presented. Staff and participating students were available to chat to visitors and overall feedback was positive.

Figure 5

To complement the online and physical exposition of the project, a comprehensive paper covering the life of the project, the findings, and recommendations will be targeted at an appropriate publication and a complementary conference presentation is planned in order to ensure broad dissemination across the art education sector.

Conclusion

Survey feedback and anecdotal evidence suggests that the aims of DACii were addressed throughout the curriculum phase, as students are eager to expand their theoretical skills not only within game art practice but also beyond into other areas of design and visualisation. Many students also believed that the use of research questions during this project has better equipped them for future study. It is hoped this will enable the students to progress successfully into honours research and industrial roles.

At Abertay, the project team have work closely with the programme team to use these findings to inform curriculum development beyond this one semester module. The team have ensured that in the redesign of the programme, there is scope for dedicated research projects from year one of the Computer Arts programme, and that multidisciplinary teams are promoted within the second and third years. The project is also likely to have an impact on teaching in terms of development of interdisciplinary course materials and the use of HCI technology in classes. This should enhance student experience, exposing arts students to the challenges (both conceptual and technical) that they will face upon graduation. In particular, we hope that future Computer Arts graduates will leave university with the confidence, knowledge, and skills to help grow the UK games and digital media sectors through innovative thinking, interdisciplinary collaboration, and entrepreneurship.

Contact information

Lynn Parker l.parker@abertay.ac.uk

Robin Sloan r.sloan@abertay.ac.uk

Biographies

Lynn Parker is the programme tutor for BA (Hons) Computer Arts within the Institute of Arts, Media and Computer Games. She holds an MSc in Animation and Visualisation and delivers animation modules across undergraduate and postgraduate game art courses. Lynn has professional and academic experience in 3D production having worked in historical visualization and game prototyping.

Dr Robin Sloan recently completed his PhD research in emotional avatars, is experienced in the design and execution of both qualitative and quantitative research methods, and is currently employed as a Lecturer in Computer Arts. Robin has academic and professional experience in game art production and has previously developed 3D interactive artwork for both scientific visualization and project promotion.

Santiago Martinez is currently studying a PhD in Human Computer Interaction at the University of Abertay Dundee. Santiago has a background in Computer Science and Engineering. He studied an MPhil in software engineering and Artificial Intelligence in Malaga before moving to the University of Abertay. Santiago is interested in IT design and usability in a social context.

References

Backlund, P. Engstrom, H. Hammar, C. Johannesson, M. and Lebram, M. (2007). ‘Sidh – a game based firefighter training simulation’, IV ’07, July 4-6, Zurich, Switzerland.

Brutzman, D. (2002) ‘Teaching 3D modeling and simulation: virtual kelp forest case study’, Web3D ’02, February pp.24-28, Tempe, Arizona.

Ciavarelli, A. Platte, W.L. and Powers, J.J. (2009) ‘Teaching and assessing complex skills in simulation with application to rifle marksmanship training’, Interservices/Industry Training, Simulation & Education Conference, November 29-December 2, Orlando, Florida.

Cowen, N. (2010) ‘Employment drops in UK games sector’, Telegraph.co.uk, November 4 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/video-games/8109768/Employment-drops-in-UK-games-sector.html. Date accessed 06/11/10.

Isaacs, J. P. Falconer, R.E. Gilmour, D.J. and Blackwood, D.J. (2010), ‘Sustainable urban developments: stakeholder engagement through 3D visualization’, CGIM 2010, February 17, Innsbruck, Austria.

Makila, T. Hakonen, H. Smed, J. and Best, A. (2009) ‘Three approaches towards teaching game production’, Design and Use of Serious Games, 37(1), pp.3-18.

Nazir, A. Lim, M.L. Kriegel, M. Aylett, R. Cawsey, A. Enz, S. Rizzo, P. and Hall, L. (2008) ‘ORIENT: an inter-cultural role-play game’. NILE 2008, August 6-8, Edinburgh, UK.

Rosser, J.C. Lynch, P.J. Cuddihy, L. Gentile, D.A. Klonsky, J. and Merrel, R. (2007) ‘The impact of video games on training surgeons in the 21st century’ Archives of Surgery, 142(2), pp.181-186.

Vernon, T. and Peckham, D. (2002) ‘The benefits of 3D modeling and animation in medical teaching’, Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 25(4), pp.142-148.

Photos: Lynn Parker

Figure 1: Students from the Summer Phase of the project met with the West Sands ranger to find out more about the coastal defences in St. Andrews, and to gather vital research information and imagery to inform their prototype application.

Figure 2: Computer Arts student Adam Dart created an interactive piece which could be used to demonstrate the visible signs of decay on new architectural designs.

Figure 3: Computer Arts student Alastair Low was inspired by recent discussion of the various applications of stereoscopic 3D (S3D), and proposed to design a game in which S3D would enhance the telling of game stories. Different views of the game world could be shown to the player through the use of polarised glasses, controlling which scene the user could see.

Figure 4: The student group from the summer phase exhibit their prototype to university staff, students and the partner division for feedback.

Figure 5: The final DACii exhibition provided an opportunity for internal and external staff and students to meet the project team and student participants, and to try out prototypes from the summer and curriculum phase of the project. The exhibition was held as part of the SICSA meeting hosted at the University of Abertay Dundee on February 29th 2012.

Header image: section from Figure 4

Back to Art Design Media Learning and Teaching Projects 2011-12 - Final Reports