Autographic Photographic: developing critical analysis through slow doing and embodied thinking

Paul Grivell and Claire Scanlon, Northbrook College Sussex

Photography students’ critical analysis of their own images traditionally occurs in written self-evaluations and ‘critiques’ where their photographs are viewed and discussed. Analysis is thus often understood to be a physically remote conceptual process that takes place in the realm of language, beyond the doing of photography. In the context of ubiquitous digital technologies that enable st...

Keywords: photography, neuro-aesthetics, critical analysis, embodied learning, autographic techniques

Abstract

Photography students’ critical analysis of their own images traditionally occurs in written self-evaluations and ‘critiques’ where their photographs are viewed and discussed. Analysis is thus often understood to be a physically remote conceptual process that takes place in the realm of language, beyond the doing of photography.

In the context of ubiquitous digital technologies that enable students to create and disseminate images at high volume and speed, this paper reports on research into the use of time and labour-intensive autographic techniques as methods of formative image analysis for students working with photography in an art and design context.

(Post-rationalised) Rationale

Conjecture: What’s The Matter With How Photography Students Do & Think Their Subject?

This study is based on a hunch - that students of photography might gain a deeper understanding of their habits of perception and image-construction by applying drawing and print-making processes to their own photographs. It’s premised on a concern that the technologies of photography may mitigate against the development of that understanding.

We contend that the speed of image production that the camera facilitates may short-circuit the process of ‘knowing through seeing’ inherent in slower media such as drawing. Consequently the photographic image often contains a density of immediately visible visual data that can paradoxically remain remote from students’ conscious perception.

Recent developments in the field of neuro-aesthetics bring to mind that our habits of perception are structured by a complex of psycho/symbolic associations to the visible world, as well as being conditioned by a specific socio/historic image repertoire reinforced over millennia by the evolutionary adaptations of neuro-biology (Stafford, 2007). These developments correspond with theoretical perspectives in visual culture that emphasise the importance of historically specific ‘scopic regimes’ in formulating perception (Metz, 1982; Crary, 1990; Jay, 1993; Tagg, 2009). From this it is understood that form and content are indivisibly ‘significant’ in the semantic consideration of images.

However, the rhetoric surrounding much photographic practice, derived in part from assumptions about photography’s ‘reality effect’ at the level of representation, tends to foreground an emphasis on the taking of images - wherein hunting metaphors have us aim, shoot and capture pictures of the world - rather than the role of perception in the construction of reality. Once captured, those images tend to be unproblematically displayed as evidence of that world, without reference to the complex interplay suggested above.

This ubiquitous rhetoric can work counter to the aims of photographic education, potentially foreclosing student understandings of the significance of formal issues in the construction of meaning and the critical analysis of photographic imagery. Formal considerations may then become analytically marginalised to the level of aesthetic choice, and largely discounted at the level of meaning-making.

In this sense students’ analytical awareness of the meta-structure of images may be an important aspect of their critical and creative development. Without this awareness significant elements of their photographic image-making processes are all too often experienced as given and so are uncritically reproduced in practice. Such habituated responses, reproduced without awareness, are fundamentally inhibiting for the creative-reflective practitioner in visual culture. Thus it may be argued that recognising (or indeed cognising) habituated approaches is a key threshold concept for photography students if they are to develop as practitioners (Land & Meyer, 2003).

Aims/Desired Shifts

From Taking to Making

For many students of photography the camera appears to subsume the work of co-ordinating the hand/eye/brain in representing the observable world. This given technological capacity, coupled with the rhetorical framework which foregrounds the taking rather than the making of pictures, may create a disposition towards a disembodied yet acquisitive relationship to their subject.

From Thinking as Un-doing to Thinking as Doing

Having taken their photographs in the world, students’ subsequent image analysis mostly takes place at a distance and in the realm of language - spoken and written, usually in an essay, critique or written evaluation. Often it is only in this realm that images are (post) rationalised, usually in the context of assessment requirements.

It is therefore unsurprising that students may then come to conceive of critical and analytical thinking about their practice as a largely post-hoc conceptual process - remote from other ways of knowing, disembodied from their practice and undertaken after the event of photography. Image analysis is thus often understood as a form of post-rationalisation.

In this case study we hoped to address this essentially false dichotomy of doing and thinking in order to encourage both a more mindful photographic practice, and a more embodied thinking on and in that practice.

Starting Points

Troubling Looking - The Itchy-Scratchy Photograph

Charlotte Cotton defines an itchy-scratchy image thus:

I think of it as the picture/s that you print up, just to a small working size, to get a look at. The ones that interest and trouble you because there is something that you don’t fully understand about them, as if you unconsciously did something. These pictures seem to signpost a new direction in a photographer’s practice, they are transitional pieces, and precursors to a new phase or project. I think all the best photographers have the guts to move beyond the pictures they already know they can make, and spend time with the itchy scratchy pictures to work out what comes next.

This description of a critical, analytical and reflective process of image evaluation, premised on a certain unease, struck us forcibly in the context of the digital image economy in which many students predominantly operate. In this digital realm students often accumulate thousands of photographs, which are stored on their cameras’ memory cards and may be downloaded to their computers or up-loaded to image hosting websites such as Flickr. The convenient speed and minimal cost of digital image production and dissemination can result in students spending relatively little time in planning, making, looking at or thinking about their photographs, whilst feeling highly productive in their output.

To generalise, and without wishing to sound nostalgic for the ‘heritage processes’ of analogue photography, we maintain that the relative cost, slowness and labour-intensiveness of analogue image-making afford students a range of opportunities to be mindful of what they are doing - both before, during and after the moment of image exposure. Compared to digital practices these processes also tend to involve a greater degree of physical, manual and embodied engagement with the medium.

Given the reduction of these opportunities in much digital practice we adopted the idea of the itchy-scratchy image as a starting point to engage students in a sustained, reflective and embodied analysis of their own photography.

Re-cognising Habits of Perception / Bringing to Mind Tacit Knowledge

In using the starting point of the itchy-scratchy image and its quality of troublesome-ness (Perkins, 1999, Meyer & Land, 2003) an aim was to help students reconnoitre aspects of their chosen image by surfacing their habits of perception alongside formulas and conventions adopted intuitively in their image-making practices. This aim is underpinned by our understanding of the role that tacit knowledge plays in formulating students’ intuitive judgements of their work and that of others (Polanyi, 1967).

Embodying Learning - Using Autographic/Print-making Techniques

Bringing the above critical starting points together we have grounded the case-study in a model which emphasises the importance of experiential and embodied learning and an understanding of the role of the body in perception (Dewey, 1934, Merleau-Ponty, 1962, Shusterman, 2004). Given students’ readily understood conception of the camera as a disembodied eye, and their tendency to separate practice from reflection, we sought ways to slow down and embody student reflection in practice.

Thus we hoped to find out if a different sort of engagement with the photographic image, involving the body directly and taking place over an extended period of time as a laboured reflection (Whiteread, 2010), would give students alternative access points and means of developing critical and analytical skills.

Practice

Laboured Reflection

My drawings are very much part of my thinking process. They are not necessarily studies. I use them as a way of worrying through a particular aspect of something that I’m working on. (Whiteread, 2010)

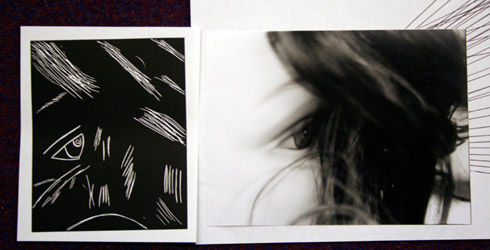

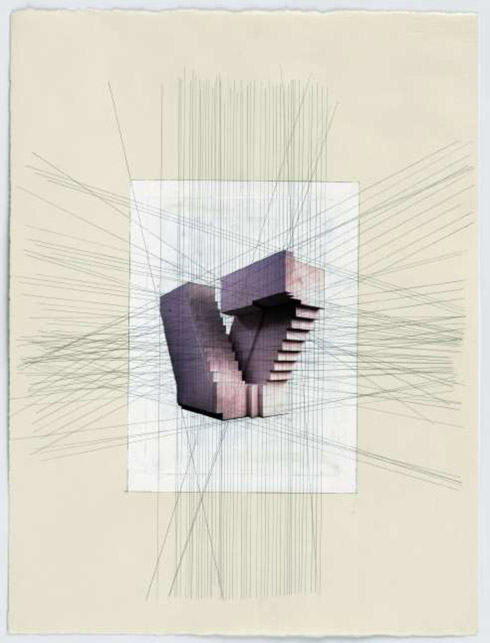

Figure 1: Rachel Whiteread Stairs 1995

Figure 1: Rachel Whiteread Stairs 1995

This drawing by Rachel Whiteread was a key text as the seed for the study. In Whiteread’s oeuvre the drawing serves as a laboured reflection on a photograph of one of her sculptures. Obviously in this context the photograph has a meta-function in her analysis of the sculpture, though we were interested in its potential as a technique to analyse the photograph specifically, with the process of drawing used as a tool for image analysis rather than as an expressive or representational practice per se.

Time-frame

Having selected a troublesome itchy-scratchy photograph from their own practice, Level 5 students on the BA (Hons.) Contemporary Photographic Arts Practice programme at Northbrook College, Sussex, were introduced to a range of autographic and printmaking processes. Over a period of five weeks, for three hours a week, they applied these techniques to their individual photographs. In week six they presented the range of outcomes from these approaches and discussed their understandings of the work made and the insights gained.

Description of Sessions

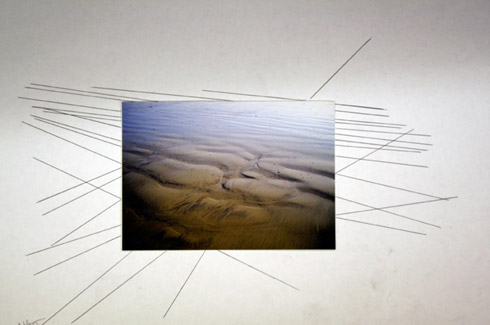

Week 1 - Linear/Vector Drawing Analysis (composition)

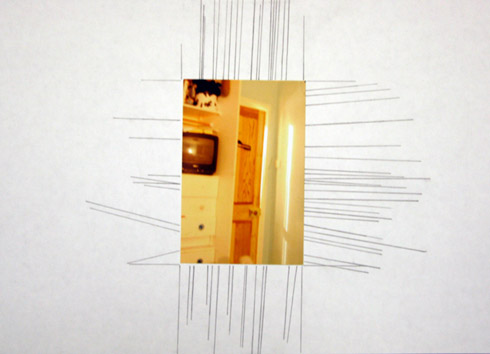

With reference to the drawing by Rachel Whiteread, students were introduced to the worrying technique of linear-vector drawing in relation to their troubling itchy-scratchy photos. Using a ruler, lines are drawn out from the image, extending the compositional structure beyond the frame. By exaggerating the horizontal, vertical and diagonal vectors, the internal dynamics of image-composition become more evident, revealing what Petherbridge (2011) refers to as the underlying ‘hegemonic linear construction’, and thus foregrounding aspects such as receding perspective (renaissance space) and grid-like frontality (modernist space).

Figure 2: student J - linear vector drawing from itchy-scratchy photograph

Figure 2: student J - linear vector drawing from itchy-scratchy photograph

Week 2 - Mono-Printing (tone-considering the relationship of pressure to light)

In mono-printing a sheet of paper is laid over an inked plate. A copy of the photograph is laid on top of the paper. Using varying degrees of pressure with an appropriate tool an impression is made on the reverse side of the paper. Having experimented with the technique, students were asked to consider the tonal range of the photographic image and apply relative degrees of pressure to indicate lightness or darkness - less pressure, more light, and more pressure, less light. This process reveals the relative contrast (chiaroscuro) of an image.

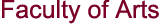

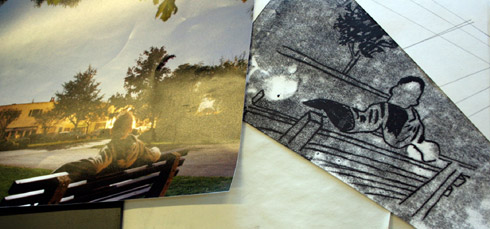

Figure 3: student J - itchy-scratchy photo and mono-print

Figure 3: student J - itchy-scratchy photo and mono-print

Week 3 - Lino-Cut Printing (figure/ground - considering negative space)

In lino-cut printing the negative space of an image (the ground) is produced by removing material from the printing block. Positive marks (the figure) are produced by what remains on the lino, as this is where the ink will adhere. The lino is inked-up, a sheet of paper is put down and pressure is applied to produce the mirror image. This technique requires a counter-intuitive understanding of image production, rather like a photographic negative, as the positive cutting action produces an absence in the image. The photographic image is transposed onto lino by tracing and the negative space is then cut away, exposing a simplified relationship between figure and ground. This helps reveal underlying compositional structures within the frame.

Figure 4: student J - lino-cut print from itchy-scratchy photo

Figure 4: student J - lino-cut print from itchy-scratchy photo

Weeks 4 and 5 - Photo Silk-Screen Printing

Used by many significant artists and designers in the 20th century - most notably Andy Warhol, to produce some of the most iconic images in the history of visual culture – the photo silk-screen technique represents the perfect marriage of photographic and fine-art image-making processes. Contextualised as such, students prepared high contrast transparencies of their images using digital manipulation and photocopying for use in the silk-screen process. Some students worked with the outcomes of the previous techniques or composites of their images rather than the original photographs, as these were more suitable for the silk-screen process.

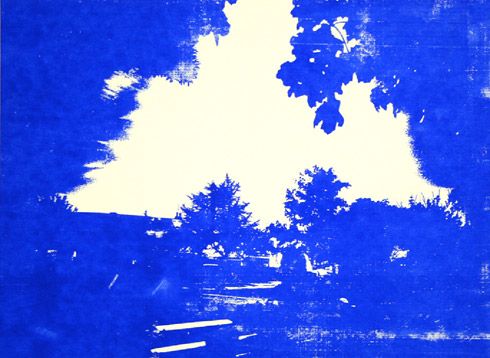

Figure 5: student J - silkscreen image

Figure 5: student J - silkscreen image

Week 6 - Concluding Critique with Questionnaire (audio-recorded)

Throughout the practical sessions students were asked to reflect on their experience of each process via a set of questions requiring a written response. Then, at a final critique they engaged in a discussion of their overall experience, which was audio recorded alongside the photographic documentation of their visual outcomes. In this context they were asked to reconsider their initial written responses to the questions.

The students’ written responses to the key questions, their comments made in the audio recorded final critique, and the visual work they made in the context of the five sessions, have together provided a wealth of material for consideration. From this we have chosen representative samples of students’ written and verbal responses to our questions. These are presented below, alongside examples of their visual work made during the sessions.

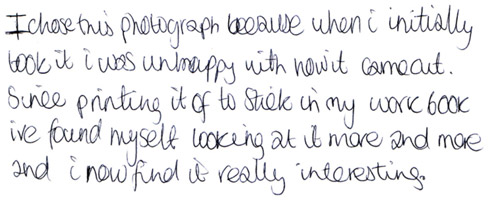

Question 1: What was it about your photograph that made you choose it to work with?

Figure 6: student L - Q1 written response

Figure 6: student L - Q1 written response

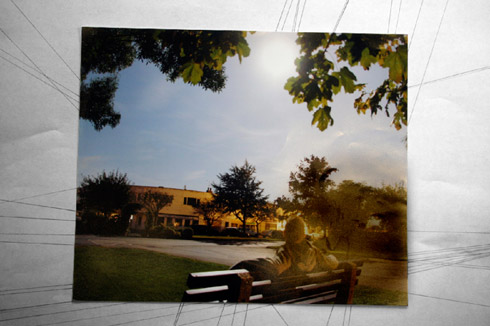

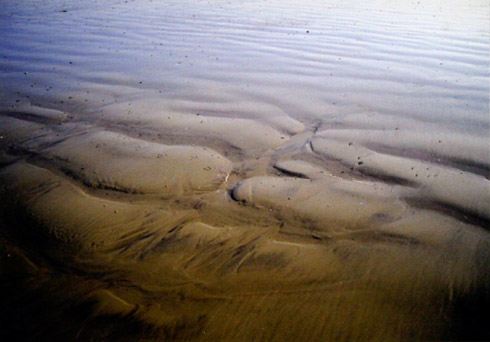

Figure 7: student L – itchy-scratchy image

Figure 7: student L – itchy-scratchy image

Figure 8: student A - Q1 written response

Figure 8: student A - Q1 written response

Figure 9: student A – itchy-scratchy image

Figure 9: student A – itchy-scratchy image

Question 2: Did the linear network drawing analysis exercise reveal something about the photograph you had not noticed or consciously considered before, and if so, what was it?

Figure 10: student A - Q2 written response

Figure 10: student A - Q2 written response

Figure 11: student A - linear vector drawing from itchy scratchy image

Figure 11: student A - linear vector drawing from itchy scratchy image

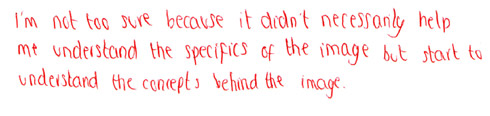

Figure 12: student L – Q2 written response

Figure 12: student L – Q2 written response

Figure 13: student L – linear vector drawing from itchy-scratchy image

Figure 13: student L – linear vector drawing from itchy-scratchy image

Question 3: Did it help you to think differently or understand more about the photograph to work physically with it through drawing and printmaking?

Student L (oral response): ‘…not entirely…I just enjoyed making it into something I found quite interesting.’

Student AM (oral response): ‘It made the point that it doesn’t have to stop there…the photograph isn’t the end of the process…it can be developed further...To have a better understanding of why you do things…how you take a picture…how you frame things…to understand how your practice works.’

Figure 14: student E – Q3 written response

Figure 14: student E – Q3 written response

Question 4: Would you use this type of autographic analysis again? Please say why if the answer is either positive or negative.

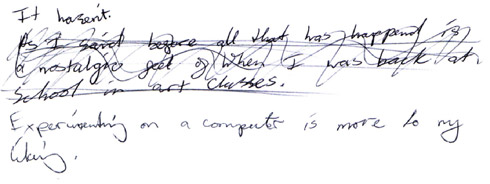

Student A (oral response): ‘It reminded me of when I was back at school doing art…. and I hated art.’

Figure 15: student E – Q4 written response

Figure 15: student E – Q4 written response

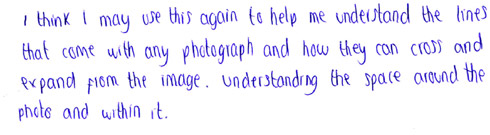

Figure 16: student B – Q4 written response

Figure 16: student B – Q4 written response

Figure 17: student B – Q4 written response (on further reflection)

Figure 17: student B – Q4 written response (on further reflection)

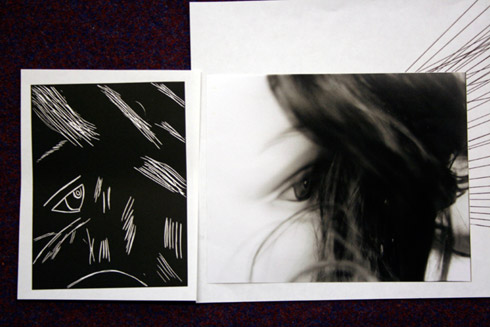

Figure 18: student B - linocut and itchy scratchy image

Figure 18: student B - linocut and itchy scratchy image

Question 5: On reflection, how has the time spent with your image helped you to consider the implicit socio-cultural formations in your habits of perception and the subsequent conventions of representation you employ?

Student L (oral response):

My image came from my ‘time and space’ project… it’s just of the corner of my room in candle light…but it was really over-exposed…I first thought I would delete it because it was so dark, but I found it really interesting and then I thought we are meant to keep our mistakes, so I didn’t, and I’ve had it on my wall ever since…so I thought I would work with it (as a real itchy scratchy image). And it showed how I’d really composed it unconsciously, so it really made me look into what was a mundane thing to me … so I really enjoyed trying to dissect it … At first I didn’t think it was visually interesting, but the drawing made me realise how I had actually composed it….

Figure 19: student A – Q5 written response

Figure 19: student A – Q5 written response

Drawing Conclusions

Subsequent consideration of students’ visual outcomes and their verbal and written responses led us to the following provisional observations on the value of the project and the issues it raised.

Students’ prior experience of being taught art - both positive and negative - influenced their attitudes towards the study aims. As a result, student responses divided on the basis of whether they found the processes enjoyable or difficult and/or troubling in relation to their understanding of their subject area and the disciplinary context. Regardless of this bias however, it was notable that most of the students enjoyed the developmental aspects of the processes and techniques over the more demanding aspects of developing critical reflection. So in this sense there were contradictory tensions at work in the study aims from the outset. As a result, student responses were in general couched in terms of levels of enjoyment derived, rather than levels of understanding attained. For some students the merit of the autographic processes in developing analytical skills were attributed to the duration of attention rather than to the form of that attention. Indeed, some students expressed a preference for the more remote process of just looking in order to analyse images. This may be symptomatic of a wider cultural passivity in the realm of visual media consumption (Debord, 1967), but also suggests an implicit dualism in the students’ perception of learning. This reinforces our initial conjecture that students tend to understand image analysis as an activity conducted after-the-event of photography.

The difficulty in reconciling the enjoyment of the technical processes with the potentially challenging processes of analysis may be key to the contradictory responses the study provoked. It has been noted by Spendlove (2007) that:

Emotional state has also been considered to have a direct relationship with cognitive appraisal and how artwork is perceived and evaluated with affective states influencing the way an artwork is perceived and processed. This results in more holistic processing when the perceiver is in a positive mood, and more analytical processing when in a negative state (p.162).

The association of emotional negativity with analysis has inevitable implications for learning, especially when coupled with the complex emotional factors of uncertainty and personal risk associated with creative practice - a problem now being recognised in research into the ‘crit’, as the predominant form of assessment in art and design education (Blair, Blythman & Orr, 2007). The aim of our study was to (re)engage students with image analysis by making the process interactive and pleasurable. Physical, technical processes served to link the development of higher cognitive faculties (analysis) with pre-linguistic play (pleasure) in order to integrate the learning experience - thus enabling students to (re)discover the bonds between curiosity, sensory pleasure and learning.

In our experience student interest in technique and skills acquisition tends to predominate over analysis and critical reflection. This is perhaps attributable to both a cultural understanding of the learning process as consumption, and to the affect of emotional negativity associated with analysis, as indicated above.

Another notable contradiction, and possible methodological aporia, was the use of the questionnaire in the study. Given the role of tacit knowledge in students’ understanding of image construction, the requirement to respond verbally or in writing to the physical processes reinforced the assumption that the analytical process necessitates a bringing into language. The written and verbal responses reflected this on-going difficulty in articulating physical experience in language, and were often contradictory or nonsensical. In some instances this was expressed (in words) as a negative feeling towards the activity, yet new insights were nonetheless revealed. Whilst not entirely surfacing student understanding, there remained a sense in which the activities certainly made that understanding more available, acting as a bridge to further understanding. As previously suggested the tendency to see image-construction in photography predominantly as a simple act of framing of a given world demonstrates a host of tacit assumptions about perception and cognition that take time to excavate. The very ideas of habits of perception and conventions of representation may have been too unfamiliar, threatening or simply too deeply buried to consider for some students participating in this study.

In Summary

We can know more than we can tell (Polanyi, 1967).

Polanyi (1967) states that hunches are worth pursuing as gestures to be followed with curiosity, and following our hunch we are reminded to accept that not all knowledge is (or should be) immediately available to the intellect in language. Students told us they didn’t get it or couldn’t see the point, or weren’t sure if they had grasped it with two hands or said they didn’t know or couldn’t tell if or how the drawing and printmaking processes had helped them to think about their photographs. Yet they also said that they had been made to consciously question their photographs, that it was interesting to extend the image beyond the frame, that it reminded them the image was never just finished. They told us that they had enjoyed the process, and if not the process then the outcome of the process. They said they were interested in the ideas and might or would use the techniques again, suggesting that something in the hunch is worth pursuing in future teaching. Perhaps when uncertainty is expressed it is a marker of a threshold moment and therefore an opportunity for learning to occur.

Not all learning is progressive in the manner proposed by some pedagogic theory -for example the ‘SOLO’ taxonomy of Biggs & Collis (1982). Some learning may need to be recursive. Multi-sensory approaches in HE that emphasise play may feel alien or childish to students at first, but they can engender a protracted engagement with their subject that may result in real insight. The workshop context may also provide the space and time for students to become reflectively absorbed in the creative process, as a necessary condition for the promotion of a deep approach to learning. Thus we argue that the primacy of drawing in the realm of visual representation is key in this sense, and (re)developing autographic techniques as learning tools may be invaluable in the context of photographic art education.

Biographies

Claire Scanlon and Paul Grivell work together on photography, media and art programmes across FE and HE at Northbrook College, Sussex. They also collaborate as artists, researchers and writers.

References

Biggs, J. and Collis, K. (1982) Evaluating the Quality of Learning: the SOLO Taxonomy, New York, Academic Press.

Crary, J. (1990) Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, Massachusetts, MIT Press.

Debord, G. (1967) Society of the Spectacle, New York, Zone Books.

Dewey, J. (1934) Art as Experience, New York, The Berkeley Publishing Group.

Jay, M. (1993) Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought, Berkley, University of California Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962) Phenomenology of Perception, Abingdon, Routledge.

Metz, C. (1982) The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Meyer, J. H. F. and Land, R. (2003) ‘Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge – Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practising’. In Rust, C. (ed) Improving Student Learning – Ten Years On, Oxford, OCSLD

Perkins, D. (1999) The Many Faces of Constructivism, Educational Leadership, Vol. 57 Nos 3.

Petherbridge, D. (2010) The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice, New Haven, Yale University Press.

Polanyi, M. (1967) The Tacit Dimension, New York, Anchor Books.

Shusterman, R. (2004) ‘Somaesthetics & Education: Exploring the Terrain’. In L. Bresler (ed) Knowing Bodies Moving Minds: Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Spendlove, D. (2007) ‘A Conceptualisation of Emotion within Art and Design Education: A Creative, Learning and Product-Orientated Triadic Schema.’ International Journal of Art and Design Education 26(2) pp155-166.

Stafford, B.M. (2007) Echo Objects: The Cognitive Work of Images, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Tagg, J. (2009) The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

URLs

http://www.adm.heacademy.ac.uk/projects/adm-hea-projects/learning-and-teaching-projects/critiquing-the-crit for Bernadette Blair, Margo Blythman & Susan Orr’s ADM-HEA report ‘Critiquing The Crit’, 2007.

http://www.permanentgallery.com/wp/?page_id=171 for Charlotte Cotton’s definition of an itchy-scratchy image.

http://arttattler.com/archiverachelwhiteread.html and

http://www.tate.org.uk/tateetc/issue20/rachelwhiteread.htm for Rachel Whiteread’s account of her use of drawing as a laboured reflection.

Images: all supplied by the authors

Header and listing image: sections taken from Figure 18, student B - linocut and itchy scratchy image