Higher Education work placements in the creative industries: good placements for all students?

Kim Allen, London Metropolitan University and Jocey Quinn, Plymouth University

This article reports on a small-scale qualitative study into equality issues in higher education work placements undertaken in the creative sector. The study revealed a range of equality issues students encountered both in terms of accessing work placements and making the most of these. This article provides an overview of these issues and presents a series of recommendations for institutions ...

Keywords: employability, inequality, work placements

Abstract

This article reports on a small-scale qualitative study into equality issues in higher education work placements undertaken in the creative sector. The study revealed a range of equality issues students encountered both in terms of accessing work placements and making the most of these. This article provides an overview of these issues and presents a series of recommendations for institutions and individuals supporting teaching, learning and employability within art, design and media disciplines to use to address these equality issues within their practice.

Why are student work placements important in the creative industries?

The importance of work placements can't be underestimated. Work placements are considered a vital way of enhancing students’ employability. They can increase students’ knowledge of the workplace, improve their communication skills and self-confidence, and provide a useful arena to test out possible careers. Not only this, employers increasingly value prior experience over qualifications.

While rising numbers of young people are studying courses associated with these careers in these sectors, including those from ‘non-traditional’ backgrounds (Dann et al., 2009), this has not been matched by employer demand, with an oversupply of graduates competing for jobs in the creative sector. Indeed, just last year Tom Bewick, the then-chief executive of the sector skills council, Creative and Cultural Skills, stated that ‘at any one time there are 180,000 courses related to creative and cultural industries, yet only 6000 vacancies’ (Bewick, 2010). As Phillip Cowen has previously written about in this publication, declining graduate employment opportunities create a great deal of anxiety for students who have chosen a career in these sectors (2009).

In the current economic context it is anticipated that even more students will depend on work placements to boost their marketability among employers as they fight for a dwindling number of jobs. In a recent longitudinal study of creative graduates in the UK, Linda Ball and colleagues reflect on the significance of work placements as a prerequisite for a career in the sector:

Post‐graduation internships and working unpaid are an established feature of the creative industries landscape, as a common strategy for finding work or gaining experience (Ball et al., 2010, p.2)

They go on to argue that the current economic downturn demands graduates to be even more adaptable, ‘resourceful and willing to work unpaid’. The increasing reliance on work placements, including unpaid placements, as a means of accessing the sector raises important questions about equality and fair access to work placement opportunities and the creative sector more generally.

There has been much press attention over the last year about the exploitation of students through unpaid internships, particularly within the creative industries. These reports and campaigns paint only a partial picture of the embedded and vast inequalities at play and neglect that some groups of students fare much worse in this culture than others.

Unequal opportunities to access and undertake placements not only present consequences for student employability, but also for workforce diversity. Currently the sector is characterised by a ‘chronic’ lack of ethnic and social diversity, as well as an under-representation of women and disabled workers (Hutton et al., 2007). There has been growing recognition that more needs to be done to tackle the forms of disadvantage that prevent these groups from accessing and remaining in the sector. Work placements can play an important role within this and higher education institutions (HEIs) therefore have a real responsibility – and opportunity – to help break down these barriers.

This article reports on a research project that explored equality issues in higher education work placements in the creative sector. Conducted by then members of the Institute for Policy Studies in Education at London Metropolitan University, the study was commissioned by the Equality Challenge Unit (ECU), the equality and diversity body or Higher Education in the UK.

What was the purpose of our research?

Aims

The study had two key aims:

-

To explore how HEIs provide positive and inclusive work placement experiences for students from equality groups (disabled students, black and minority ethnic (BME) students and students entering sectors where significant gender imbalances exist) that will enhance their future employment prospects in the creative sector.

-

To develop practical resources to facilitate inclusive work placements for those in higher education.

Definitions

Equality groups: This research focused on disabled students, BME students and students entering sectors where significant gender imbalances exist. However, the research team also recognized social class as a key equality issue and therefore the experiences of working-class students were also attended to.

Work placements: Work placement experiences can encompass many different types of work-based learning (Little and Harvey, 2006). This research expanded on rather narrow definitions of work placement that refer only to formal, planned periods of work in the industry linked to a programme of study, to include independent placements that may not be formally supported by institutions but are encouraged or expected as a central aspect of students’ learning and preparation for employment.

The creative sector: In this research we used the Department for Culture, Media and Sport’s definition of the ‘creative industries’ (DCMS 2008), including sectors ranging from advertising and architecture through to film, TV and radio.

Methods

In this qualitative study, in-depth interviews were conducted with 26 students from across the key equality groups, enrolled on courses across a range of disciplines including Fashion, Media, Art, Architecture and Design. Students had conducted placements across the sector in organizations and with employers including design studios, fashion houses, television broadcasters and architecture firms. Placements included industry placements or sandwich years as well as internships and shorter term placements of several days or weeks. Interviews were also conducted with staff from five specialist and non-specialist HEIs across England and Wales, including Careers Service managers, Placement Officers and academic staff. Additionally, interviews were conducted with 11 employers from across the sector who host work placements. Interviews were designed to shed light on the equality issues experienced by students in the work placement process, HEIs’ policies and procedures for supporting students undertaking work placements, and employers’ practices in offering placements and supporting students from these equality groups.

In this article we draw mainly on the data from the student interviews. Further findings can be found in the main report.

What did we discover about student experiences?

While work placements did not always feature as part of a programme of study, they were considered by staff, students and employers as highly significant to students’ employability. Students were strongly encouraged, if not expected, to undertake work placements. However, locating a ‘good’ placement and getting the best from it was highly dependent on students’ access to social, economic and cultural resources, such as access to industry networks, the money to undertake unpaid or lengthy placements, and knowing how to ‘sell yourself’ to employers. These resources are not distributed equally and, in this research, students who lacked these resources were disadvantaged in both finding and successfully completing meaningful work placements. Furthermore, disabled students and female students undertaking placements in male-dominated sectors faced unique obstacles. These issues are briefly discussed below.

Using contacts and ‘selling yourself’

A consistent theme in interviews was the premium placed on students locating placements themselves using their own contacts rather than asking for support from their university. This reflects a wider culture of word-of-mouth recruitment within the sector. One consequence of this was that students, often those from professional middle-class families, who had friends or relatives in the creative industries were at a clear advantage in locating placement opportunities. Not all students knew people who worked in the sector who could help them locate placement opportunities, and many discussed the frustration of ‘cold-calling’ employers or anonymously responding to adverts which some students felt were less likely to result in a placement than if they had been recommended.

As well as having access to industry networks, getting a ‘good’ placement also requires knowledge of how the placement process and the industry works – for example, knowing where to look for opportunities, or how to get your CV noticed amongst hundreds of other applicants – and having the confidence and know-how to market yourself to employers. As one student explained, ‘it’s also about confidence to go out there and sell yourself’. Not all students had this knowledge and confidence to navigate the placement process, particularly working-class students.

Being unpaid is the norm

Unpaid placements featured predominantly across students’ accounts. Some students, specifically those undertaking ‘sandwich’ placements (a year in the industry) received some payment. However the majority had worked for free or with minimal expenses. This included incidences where students should have been paid national minimum wage (NMW), for example those placements which students took externally to their course and when they were doing work that went beyond ‘work-shadowing’.

Currently there is a real lack of clarity about what is considered work experience and what is paid labour, and this requires urgent attention in order to reduce the exploitation of students and address inequalities in access. The Arts Council England and Creative and Cultural Skills have recently launched a set of guidelines for organisations providing internships (see www.artscouncil.org.uk/media/uploads/internships_in_the_arts_final.pdf) which includes guidance for employers on their responsibilities and legal obligations.

In our study students – and to some extent staff and employers – were unaware of the legislation surrounding payment for work placements, or at best were confused by how it affected them. While a number of students raised concerns about the prevalence of unpaid placements, it was common for them to suggest that there was little they could do about this, because it was ‘industry standard’ and getting experience was so valuable. However, the normalisation of unpaid placements significantly impacted upon working-class students’ choice of placement, leading to a self-selection of how many and what kinds of placements they could undertake on the basis of their financial situation. This included taking shorter-term placements, choosing placements near home, or only undertaking one placement. Many of the working-class students discussed the difficulties of juggling placements with the paid part-time work. There is great inequality in this process, where students from more affluent families have greater choice in which, and how many, placements they can undertake, and for how long. One working-class student reflected on this injustice:

I only did the one placement. Other people did additional stuff but a lot of them like the London scene, and they were having funding from their parents: they had their flat paid for them, all their degree paid for them ....for me it was a struggle. My uni work did suffer because I was working part-time in a bar as well, until late. I couldn’t afford to go and do six weeks unpaid.

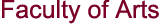

Figure 1: Student toolkit poster

Figure 1: Student toolkit poster

Hiding disabilities and limiting choices

While many of the disabled students in the study talked positively about the support offered to them within their university, they often discussed feeling uncertain and uncomfortable about whether and how to disclose their disability to employers when on placement. Many raised concerns that they would be judged as ‘stupid’ or ‘not capable’, be singled out for special treatment, or simply mis-understood. As one dyslexic student explained:

It’s just scary. I don’t want to make them think I’m stupid, but I don’t work like everybody else. I’m worried that I get penalised because I work differently or think differently or maybe I do things differently.

It was also evident that a process of self-selection was occurring with some disabled students, where these students appeared to be undertaking placements in organisations with which they were familiar, or that they felt would be more equipped to make appropriate adjustments. This included students who did placements in public sector organisations, which were felt to be better able to support disabled workers. This means that these students do not have the same choices as other students.

Being female in a ‘man’s world’

Many of the female students we interviewed who undertook placements in sectors of particular gender imbalance encountered negative gendered perceptions of ‘women’s work’ and challenging work practices and cultures. Some female students, particularly those who had undertaken placements involving technical or manual work, such as camera operation or set-design, felt that low expectations were placed on their capabilities to do the work, and reported being ‘tested’ by male colleagues. One student explained: ‘there is the attitude of well, actually, we know better. “we are men, she doesn’t know”.’ Another told us:

It was a little bit of a shock to the system at first because they are men and some of the jokes they come out with […] It is a male environment.’ ‘Sometimes they might look at me and think “how can little old me handle it?” I do feel that sometimes it is going to be a disadvantage.

Can’t speak / won’t speak about inequalities

While students discussed a range of challenges and barriers within the placement experience, described above, there was great ambiguity around how to articulate and respond to these. In this research a common response to issues of inequality in the work placement process among students – and among many of the HEI staff and employers – was the perception that ‘this is how it is’ and therefore that inequalities had to be tolerated and individually managed.

Students talked about ‘just dealing’ with unpaid work, ‘just being more driven’ when encountering gender stereotypes, or creating their own solutions to challenges rather than asking for help. This was particularly evident in discussions with disabled students on the topic of disclosure, where it was common for students to assert that their disability was something they had to work around. Typical of many students, one participant told us: ‘My general attitude is, being slightly hard of hearing, I just sort of ignore it or pretend like I’m fine.’

This resistance to naming and challenging inequalities among students poses real challenges for HEI staff who are committed to addressing them, and we attend to this issue in our recommendations.

(Not) fitting in

As discussed previously, the creative industries workforce is characterised by a lack of diversity and this did not go unnoticed by the students who took part in this research, affecting how they felt about their work placement experience and future employment. Several of the BME students discussed an awareness of being in the minority at their work placement. Similarly some working-class students also discussed feeling out of place. One working-class student explained her sense of not-belonging in a middle-class sector:

You feel that you’re lower than them, it was even the way they talked. You know like really proper. Obviously you should talk properly and all that, but it just throws you off a little bit when you arrive. It’s like you’ve not got enough money and the people you work with have a totally different lifestyle.

Feelings of being ‘different’ and ‘out of place’ on their placement can have consequences for students’ aspirations and career decisions, with students in this study rethinking their career aspirations on the basis of their unsatisfactory and sometimes unsettling work placement experiences.

What can we do about it?: some practical suggestions

Higher education staff face a difficult situation. HEIs are under increasing pressures to boost the employability of their students regardless of the fraught economic climate. However, they also have a responsibility to ensure equality of experience and outcomes for their students in all aspects of their university experience. Work placements play a significant role in students’ preparation for employment, even if placements are not formally recognised as part of a programme of study. Addressing inequalities in work placement practices would not only provide greater equity in students’ experiences and labour market transitions, it would also work towards supporting fairer access and greater diversity in one of the key growth sectors in the UK economy.

Of course HEIs can’t do this alone: achieving inclusive and meaningful work placements for all students requires the commitment and collaborative efforts of higher education institutions, employers and students and above all a cultural change in the sector. However, there is much that HE staff can do to contribute to these changes.

On a general level, work placements need to be recognised as an equality issue. HEIs need to recognise the different and complex barriers students face and support their students, both in finding placements and ensuring that the student and the employer get an equitable and meaningful placement experience.

To help HEIs develop more inclusive and effective work placement practices and policies, we offer the following suggestions, based on the research:

Collaborative working and reviewing of procedures

-

Work placements need to be reflected in HEIs’ existing equality schemes and should be coupled with systematic and joined-up procedures, developed through collaborative working between all relevant staff and agencies within the HEI.

-

HEIs should review work placement arrangements and policies to address equality issues in accordance with guidance provided by the existing public sector equality duties. This can be supported by developing procedures to gather feedback from students and to monitor the take-up and impact of work placements by different equality groups.

-

Equality and diversity training should be given to all staff who are involved in work placements, whether directly or indirectly. This should help them to identify and address equality issues such as the different resources available to students which help or hinder their success.

Better support for students

-

To increase students’ awareness of their legal rights and employer obligations regarding pay, hours and fair treatment in the workplace, HEIs should provide clear guidance and advice to students.

-

Limited resources mean that management and monitoring of work placements by HEI staff can be restricted. HEIs should assess how resources may best be used to provide maximum support for students on placement. This could be through a placement mentor who maintains contact, or through online forums enabling students to keep in contact with staff and other students while on placement.

-

HEIs should work to identify and widely promote funding opportunities for placements, such as bursaries, or utilising central or local government initiatives, as well as schemes specifically targeted at particular groups, such as BME or disabled students.

Developing a language of equality and diversity

-

Inequalities within HE work placements were often seen as the norm, something to be tolerated and managed individually. HEIs should consider how they can help create a safe environment in which students can discuss and identify these issues of inequality. This might mean including virtual or physical spaces for students to feedback on and share their experiences with each other.

-

Similarly, HEIs should develop dialogue with employers about equality issues and the opportunities for diversity within the sector.

-

Embedding a language of equality and diversity more broadly within curriculum will enable students to think about equality and diversity now, and the potential for transforming and having a positive impact on practices within their future workplace and as cultural producers. This might take the form of a core module on equality and diversity issues in the sector.

How to find out more about the research and how you can achieve more equitable work placement practices:

Figure 2: Covers from staff and student toolkit leaflets

Figure 2: Covers from staff and student toolkit leaflets

Based on the recommendations of the report, we developed two toolkit leaflets prepared specifically for careers and placement staff, and for students. These leaflets raise awareness of the equality issues and provide examples and practical suggestions of how staff – and students – can address inequalities in work placements. Toolkits and the research report can be downloaded from the ECU website: www.ecu.ac.uk/publications/work-placements-report

The toolkits are also available in hard copy. If you would like to receive free hard copies of the toolkits for your institution, please email your request to pubs@ecu.ac.uk

Contact information: k.allen@londonmet.ac.uk

Biographies

Dr Kim Allen is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies in Education (IPSE) at London Metropolitan University. Kim is a sociologist of education and her research focuses on young people’s career aspirations and issues of equality and diversity in the creative industries. She has conducted a number of studies in this area including her doctoral research on young women’s aspirations for careers in the performing arts.

Professor Jocey Quinn is based at Plymouth University. Jocey’s research focus is the inter-relationship between education and culture. She is particularly interested in both Higher Education and learning that takes place outside formal education. Her books include Learning Communities and Imagined Social Capital (2010). She has led a wide range of research projects funded by research councils, major charities and government bodies.

References

Ball, L. Pollard, E. and Stanley, N. (2010) Creative Graduates Creative Futures, London, Institute for Employment Studies.

Bewick, T. (2010) Securing the pipeline of talent to the creative industries, London, Creative & Cultural Skills.

Cowen, P.J. (2009) ‘Motivating students in the face of the media maelstrom’. Networks. November 2009. Available at www.adm.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/features/motivating-students-in-the-face-of-the-media-maelstrom

Creative and Cultural Skills (2008) Creative and cultural industry: impact and footprints 08–09, London, Creative & Cultural Skills.

Dann, L. Ware, N. and Cass, K. (2009) Tackling exclusion in the creative industries: an enterprise-led approach, London, NALN

Department for Culture Media and Sport (2008) Creative Britain: New talents for a new economy, London, Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

Hutton, W. et al (2007) Staying ahead: the economic performance of the UK’s creative industries, London, The Work Foundation.

Little, B. and Harvey, L. (2006) Learning through work placements and beyond, London, Higher Education Academy.

Skillset (2006) Employment census 2006: the results of the sixth census of the audio visual industries, London, Skillset.

Figures 1 and 2 supplied by authors

Header and listing photo: David Morris, sourced from Flickr under Creative Commons License